President Lyndon Johnson and his wife Lady Bird (seen on the right) attended the July 19, 1965, memorial service for Adlai E. Stevenson II

From the beginning of the last half of the 20th Century through the recent past, several national leaders have died at suspiciously-critical points in their careers, many by heart attacks which were presumed, but conveniently never subjected to autopsy confirmation. The ones occurring prior to January 20, 1969, the end of his presidency (even up to his death four years later) might have been added to the official “hit list” by the most likely culprit for such terminations, President Lyndon B. Johnson.

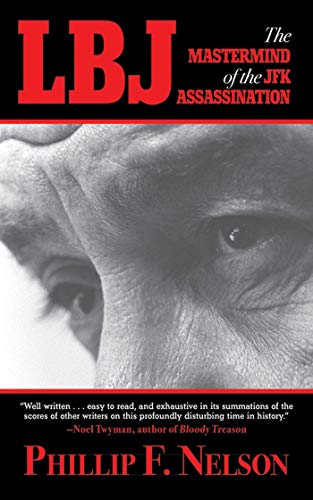

LBJ: From Mastermind t...

Best Price: $4.00

Buy New $16.58

(as of 07:20 UTC - Details)

LBJ: From Mastermind t...

Best Price: $4.00

Buy New $16.58

(as of 07:20 UTC - Details)

Despite the fact that he had never been caught “red-handed” for any murders, there are numerous cases—still open and unresolved—of which he has been accused of being the sole, or primary instigator. Among the accusers, the late Texas Ranger (later U.S. Marshal) Clint Peoples, one of the most honored, respected and impeccably credentialed of Texas lawmen, had pursued a number of such leads (including JFK’s assassination) for decades, always impeded by Johnson’s gossamer web of political, law enforcement and judiciary connections throughout the state and nation.

In 1984 (when Johnson had been dead for over a decade) Peoples convinced a Texas grand jury to change the cause of death of one of those victims, Henry Marshall—who in 1961 had been viciously beaten to death, forced to inhale a lethal dose of carbon monoxide and shot five times in his chest—from “suicide” to “homicide.” That Johnson was able to have that absurd “C.O.D.” stick, for twenty-three years, is the best illustration of his political power within Texas throughout his reign and for many years afterward.

The Still-Mysterious Death of Adlai Stevenson

Arguably one of the most prominent, highly-placed persons who suddenly, enigmatically died, on July 14, 1965, was U.N. ambassador Adlai Stevenson; he had twice (1952, 1956) been the Democratic party’s presidential nominee. According to a contemporaneous London news report, Stevenson “collapsed and died of an apparent heart attack Wednesday near the American Embassy in Grosvenor Square.” His surprising death, as an active man who still played an aggressive style of tennis at age 65, was the subject of rumors and speculations at the time, as evidenced by documents in the Harold Weisberg collection. [1]

In lengthy 1975 memoranda (prompted by the news of the CIA’s previously-secret development of the “heart attack gun”) between Weisberg and a colleague that referenced numerous other suspicious deaths the U.N. ambassador’s name was added: “One of the best-known victims could have been Adlai Stevenson, who was about to meet with NLF [National Liberation Front] and North Vietnam leaders in Paris when he was stricken on a London sidewalk.” This exchange of correspondence was prompted by the then-recent release, by the CIA, of numerous secrets, including the stunning news of a special gun that would cause the victim to have a massive heart attack that would not be noticed during an autopsy (to be further reviewed, below).

His death occurred at a time when Stevenson had become very upset with Lyndon Johnson’s Vietnam policies, and that would have caused Johnson to become very upset with him, as it was well known by all of his highest-level aides that the new president demanded absolute loyalty from all of them. Furthermore, it was also at a time when Johnson was planning to persuade Arthur Goldberg to leave the Supreme Court so that he could put his old friend Abe Fortas on it.

Apparently, Johnson let Goldberg believe that he might be reappointed—next time as “Chief Justice”—after his stint at the U.N. Goldberg’s biographer, David L. Stebenne, wrote that Arthur believed “Johnson’s request carried with it an implied promise of a return to the Court once his UN mission had been accomplished.” Moreover, Stebenne noted that Goldberg had known that Chief Justice Warren was then planning to retire and when he did, he would likely urge Johnson to appoint him as his successor, thus ending up better off than when he started. Goldberg himself would later write that “I had an exaggerated opinion of my capacities. I thought I could persuade Johnson that we were fighting the wrong war in the wrong place [and] to get out.” [2]

But there was another reason that Johnson wanted the hardline Zionist Goldberg in the UN at that point in time, and for the too-pacifist, non-doctrinaire Stevenson to be out. In the summer of 1965, one of President Johnson’s most secretive plots—in collaboration with Israeli leaders—was well underway: A plan to join Israel in a long-planned war with their neighbors, Egypt, Jordan and Syria, a supposedly “spontaneous war” scheduled well in advance for June 15, 1967 (that would be inadvertently jump-started ten days early). Johnson undoubtedly knew that a critically important sub-plot—the sinking of a U.S. naval vessel as a pretext for an attack against Egypt—would require the presence of a U.N. ambassador with unquestioned loyalty to both himself and the Zionist Israeli leadership. [3]

Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s Doubts

Traces of President Johnson’s manipulative acts had become visible in the immediate aftermath of Stevenson’s death: According to the account of New York Senator Daniel P. Moynihan, what followed was one of Johnson’s most enigmatic, cunning and deceitful maneuvers—of the numerous others—one that the highly regarded senator termed “an inexplicable disservice” to Arthur J. Goldberg, to leave his position on the Supreme Court against his wishes.

Johnson’s deceitful maneuvers were exposed by Senator Moynihan when he wrote a long “To the Editor” letter to the New York Times, which was printed on November 1, 1971. Moynihan stated: “Neither is this a service to the Court, nor yet to the confidence with which the public will read The Vantage Point” (the title of Johnson’s recently published 1971 memoirs).

Johnson had attempted to plant the lie within his book that Arthur Goldberg actually wanted, and had requested LBJ’s blessings, to resign his position as Justice of the Supreme Court in order to take the much less-prestigious position of UN ambassador.

Moynihan’s letter to the editor stated, in part: [4]

In his book former President Johnson states that en-route to Ambassador Stevenson’s funeral on July 19 he mentioned to Justice Goldberg that, “I had heard reports that he might step down from the Court and therefore might he available for another assignment.” The Justice, we are told, indicated that the reports had “substance.” The next day the Justice is said to have called Mr. Valenti to say that “the job he would accept was the U.N. Ambassadorship, if I offered it to him.”

This cannot be so. At about 4 o’clock on Saturday afternoon, July 17, 1965, I received a call from Justice Goldberg asking me to come to his home. I arrived and was told the President had asked him to take on Stevenson’s post. The Justice was in the turmoil one might expect. He had not the least desire to leave the Court. I am as certain of this as one man can be of another’s feeling. . . He cared for the Court as for few things. Only an urgent and pressing appeal from the President of the United States could weigh more heavily with him, and even then he was not certain.

[ . . . ]

Stevenson died on Wednesday [July 14, 1965]. On Friday [July 16] Arthur J. Goldberg was asked would he leave the Supreme Court, where he had only just begun ‘the richest and most satisfying’ period of his career, to reenter the Cabinet, and to assume the unrelenting responsibilities of his nation’s representative at the U.N. He accepted, in his words, “as one simply must.”

To learn now that the U.N. post was not mentioned until Tuesday [July 20], and then on Justice Goldberg’s initiative, is to gain further insight into what we have been through [obviously a reference to LBJ’s “credibility gap”]. On that very day, July 20, Mr. Johnson announced the appointment, stating, “At the insistence of the President of his country, he has accepted this call to duty.” (Emphasis added throughout).

— DANIEL P. MOYNIHAN Cambridge, Mass., Oct. 27, 1971

CBS News Analyst Eric Sevareid’s Doubts

LBJ: The Mastermind of...

Best Price: $7.91

Buy New $11.23

(as of 06:30 UTC - Details)

Stevenson’s death occurred shortly after attending a UN meeting in Geneva, Switzerland and he had stopped off in London for a few days off. Two days before he died, he had been interviewed by his long-time friend Eric Sevareid, who was then appearing on CBS News every weekday evening to give a three-minute analysis of major political events. [5]

LBJ: The Mastermind of...

Best Price: $7.91

Buy New $11.23

(as of 06:30 UTC - Details)

Stevenson’s death occurred shortly after attending a UN meeting in Geneva, Switzerland and he had stopped off in London for a few days off. Two days before he died, he had been interviewed by his long-time friend Eric Sevareid, who was then appearing on CBS News every weekday evening to give a three-minute analysis of major political events. [5]

It was under Stevenson’s influence—with help by other journalist-friends, such as Walter Lippmann—that, in the previous year, Sevareid had begun devouring himself in studying Vietnam and its history, and had come to understand that the “conflict” was not the international communist conquest portrayed by the Johnson administration but merely a civil war which presented no threats to any other nation, especially that of the United States.[6]

On Monday, July 12, 1965, Sevareid had a lengthy, heartfelt conversation with Stevenson at the U.S. embassy in London. After Stevenson’s death, the CBS newsman offered readers of Look magazine a candid profile of the statesman two days before his sudden death. Sevareid’s biographer, Raymond A. Schroth, summarized it thusly:

“Stevenson poured out his complaints about the U.N. job, his frustrations with the Vietnam peace process—giving the impression that the Johnson administration was sabotaging rather than really seeking a settlement—and said he wanted to go back to Libertyville, Illinois, see the grandchildren, and ‘sit in the shade with a glass of wine in my hand and watch the people dance’.” (Emphasis added). Undoubtedly at Johnson’s direction, his aides and associates immediately denied the charge of sabotaging peace initiatives and (quoting Schroth again), they “accused Sevareid of trying to embarrass the president.” [7]

Within the 4,000+ word Look article, Sevareid’s first paragraph began with these words: [8]

I loved Adlai Stevenson unreservedly, and for me there was a brutality about that week in mid-July when he died. On Monday, the twelfth, I had sat up with him until well past midnight, and he bared his heart in a rush of talk. What he said that night revealed a profound frustration, a certain resentment that stopped just short of bitterness. We had not talked so intimately for several years, and I went away with my feelings of sadness for him overlaid with a kind of selfish feeling of elation that our old affection had been revived and confirmed. (Emphasis added).

The most salient of the numerous points made by Sevareid in his article were:

- That he had appeared on a BBC News program the evening of Stevenson’s death to report on their conversation two days earlier, during which he “nearly broke down completely and publicly.”

- “A flurry of controversy and some angry feelings in high places resulted from what I broadcast to America that evening and from what others said. I did not report all he had told me, but I said that he was planning to resign from the UN post.”

- “From Paris, David Schoenbrun of Metromedia Stations reported a conversation of the previous week and stated that Stevenson had referred to President Lyndon B. Johnson’s intervention in the Dominican Republic as a “massive blunder.” The President, through Bill Moyers, his press secretary, responded with anger, saying it was a disservice to Stevenson’s memory to quote him when he was dead and could not answer. Later, the White House told me its reaction was directed solely at the Schoenbrun story, not at mine, but for a time I suffered painful worries that I may indeed have harmed the memory of a dear friend. I do not think so now; I think what I reported had to be reported, if the historic record is to be truthful and complete . . . In any case, Adlai’s state of mind at his death should be known, and I think it is entirely proper for me to relate it in detail now. I do so without attempting to evaluate his various remarks about high policy, but with a sense of certainty that I report him accurately.”

When they met at the American Embassy for their private and lengthy conversation, Sevareid said that he “quickly understood” that it was not to just a friendly, casual meeting: “He began almost abruptly. He simply had to get out of the U.N. job. He was tired. He was 65 years old. ‘I guess I’ve been too patient,’ he said. Then, with that wry, deprecating smile, ‘I guess that’s a character weakness of mine’.”

Sevareid then described several incidents that weighed heavily on Stevenson, never previously publicly revealed, all of which reflected poorly on President Johnson’s domineering leadership style that stymied any attempt by the highest Cabinet officials to rebut even a single sentence in television addresses prior to their airing. He cited Hubert Humphrey, McGeorge Bundy and Dean Rusk particularly for being afraid to question even the smallest points, which he felt might lead to over-commitments and future conflicted positions. When he had urged Humphrey to react to one such issue, for example, “Hubert put his finger to his lips and shook his head.” These incidents, Sevareid said, gave him the impression that Stevenson was “deeply offended” that Johnson’s leadership style discouraged any dialogue by his own highest-level officials.

The most troubling of the incidents were those which belied Johnson’s clear intent to publicly present an interest in obtaining peace agreements with North Vietnam while privately resisting any such initiatives. Sevareid described one such opportunity that Stevenson revealed to him that occurred in the autumn of 1964, when UN Secretary-General U Thant had persuaded North Vietnam officials to send an emissary to talk to an American representative in Rangoon, Burma, but that failed because: “Someone in Washington insisted that this attempt be postponed until after the Presidential election. When the election was over, U Thant again pursued the matter; Hanoi was still willing to send its man. But Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, Adlai went on, flatly opposed the attempt . . . Stevenson told me that U Thant was furious over this failure of his patient efforts, but said nothing publicly.” [9]

There were a number of other, similar, peace-seeking efforts by U Thant, with Stevenson’s consistently strong support. As recounted by Sevareid, “Adlai Stevenson, who was working closely with U Thant in these attempts, was convinced that these opportunities should have been seized, whatever their ultimate result.” For the sake of brevity in this article, the others have not been enumerated here, however, Sevareid described and summarized them and the dilemma into which Stevenson was thrust:

Remember the Liberty!:...

Best Price: $12.75

Buy New $10.00

(as of 07:20 UTC - Details)

Remember the Liberty!:...

Best Price: $12.75

Buy New $10.00

(as of 07:20 UTC - Details)

He was relating them as prime examples of the frustrations of his job at the UN. He was accustomed to making policy, not being told what the policy was to be and how he was to defend and explain it before the world. In particular, he could not bear having certain White House and State Department people whom he regarded as mere youngsters telling him what to do. He felt these men simply did not understand his difficulties at the UN, and he doubted their wisdom about this dangerous world. At times, when he was in the middle of a UN debate with a Communist adversary–on TV and before the listening world–he would receive phone calls from Washington, or notes would be slipped to him, instructing him on how he should complete his arguments. The tactic, apparently, had driven him wild. [10]

Clearly, Adlai Stevenson himself and his friend Eric Sevareid shared Senator Moynihan’s understanding about the cunning duplicitousness of President Johnson. That point was also reported by Sevareid’s biographer in the passages previously referenced, where Schroth noted that the incident “affected Eric profoundly,” as he was also struggling with attempting to understand the government’s rationale for going to war; it was repeated again when Schroth observed that Eric “had nothing to gain by reporting his encounter—other than the newsman’s satisfaction in moving his audience closer to the truth.”

The contrast in their respective fates—Goldberg’s wish to remain a Supreme Court Justice and Stevenson’s desire to retire—clashed with Johnson’s determined manipulation to be rid of Stevenson and to move his pawn Goldberg into the UN position. Eric Sevareid’s biographer Schroth had put his finger on the probable catalyst of Stevenson’s demise: One did not publicly embarrass Lyndon B. Johnson without running the risk of triggering his deadly retribution. Johnson’s bullying probably led to a communication impasse between him and Stevenson, so we will never know whether—had Adlai simply immediately resigned—he might have lived long enough to enjoy a longer life of retirement “drinking wine in the shade and watching people dance.” One thing is certain however: Stevenson’s death was considered “untimely” to almost everyone.

The one exception to that paradigm was Stevenson’s chief nemesis: President Lyndon B. Johnson.

The 1975 Revelation of the CIA’s “Heart Attack Gun”

Senators Frank Church (D-ID) and John Tower (R-TX) examining the “heart attack gun” which could shoot a frozen projectile filled with a deadly toxin that would induce a heart attack in the victim, leaving only a small red dot on their skin, and no other substance that could be detected at autopsy.

Source: Youtube “The CIA’s Heart Attack Gun”.

The “heart attack gun” shown in the photograph above—given that this particular weapon was obviously developed for that specific purpose at least five decades ago—demonstrates the certain reality of how that tool would have been put to use. Obviously, certain protocols would have been created to define who would qualify for nominating candidates for potential victims and the decision procedures—or simply conferring that authority to specific high-level officers—to control its use. Considering everything we know about Lyndon B. Johnson’s capacity for executing such orders during his reign of power, it is axiomatic that his name would be the first on that list.

That weapon has probably now become the most primitive of the CIA’s inventory of such fatality-inducing tools, given the continually-expansive nature of that organization into every facet of American life, and death—not to mention every other country on the planet where its presence is felt.

End notes:

[1] See: http://jfk.hood.edu/Collection/Weisberg%20Subject%20Index%20Files/F%20Disk/Forrestal%20James%20V/Item%2002.pdf

[2] Stebenne, David L. (1996). Arthur J. Goldberg, New Deal Liberal. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 348.

[3] See Remember the Liberty! Almost Sunk by Treason on the High Seas TrineDay Publishing, Walterville, OR, 2017

[4] See: http://jfk.hood.edu/Collection/White%20Materials/Vantage%20Point%20Installments/Vantage%2014.pdf

[5] “Stevenson’s Death in 1965 Stunned World,” Pantagraph.com, By Bill Kemp, Archivist/librarian, McLean County Museum of History, July 18, 2010

[6] Schroth, Raymond A., The American Journey of Eric Sevareid, South Royalton, Vermont: Steerforth Press, p. 368

[7] Ibid. pp. 317-319

[8] Sevareid, Eric, “The Final Troubled Hours of Adlai Stevenson,” Look magazine, November 30, 1965, pp. 81-86

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.