True Believers and the Unspeakable Chautauqua

September 1, 2010

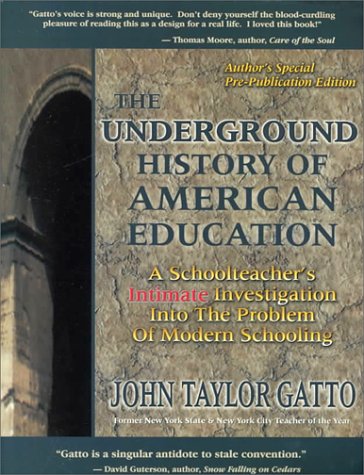

Chapter 5 of The Underground History of American Public Education

A very small group of young psychologists around the turn of the century were able to create and market a system for measuring human talent that has permeated American institutions of learning and influenced such fundamental social concepts as democracy, sanity, justice, welfare, reproductive rights, and economic progress. In creating, owning, and advertising this social technology the testers created themselves as professionals.

~ Joanne Brown, The Definition of a Profession: The Authority of Metaphor in the History of Intelligence Testing

I have undertaken to get at the facts from the point of view of the business men — citizens of the community who, after all, pay the bills and, therefore, have a right to say what they shall have in their schools. ~ Charles H. Thurber, from an address at the Annual Meeting of the National Education Association, July 9, 1897

Munsterberg And His Disciples

The self-interested have had a large hand conceiving and executing twentieth-century schooling, yet once that’s said, self-interest isn’t enough to explain the zeal in confining other people’s children in rooms, locked away from the world, the infernal zeal which, like a toadstool, keeps forcing its way to the surface in this business. Among millions of normal human beings professionally associated with the school adventure, a small band of true believers has been loose from the beginning, brothers and sisters whose eyes gleam in the dark, whose heartbeat quickens at the prospect of acting as "change agents" for a purpose beyond self-interest.

For true believers, children are test animals. The strongest belt in the engine of schooling is the strand of true belief. True believers can be located by their rhetoric; it reveals a scale of philosophical imagination which involves plans for you and me. All you need know about Mr. Laszlo, whose timeless faith song is cited in the front of this book (xiii), is that the "we" he joins himself to, the "masters who manipulate," doesn’t really include the rest of us, except as objects of the exercise. Here is a true believer in full gallop. School history is crammed with wild-eyed orators, lurking just behind the lit stage. Like Hugo Munsterberg.

The Underground Histor...

Best Price: $39.03

Buy New $180.99

(as of 07:40 UTC - Details)

The Underground Histor...

Best Price: $39.03

Buy New $180.99

(as of 07:40 UTC - Details)

Munsterberg was one of the people who was in on the birth of twentieth-century mass schooling. In 1892, a recent émigré to America from Wilhelm Wundt’s laboratory of physiological psychology at Leipzig, in Saxony, he was a Harvard Professor of Psychology. Munsterberg taught his students to look at schools as social laboratories suitable for testing theory, not as aggregates of young people pursuing their own purposes. The St. Louis Exposition of 1904 showcased his ideas for academicians all over the world, and the popular press made his notions familiar to upper-middle classes horrified by the unfamiliar family ways of immigrants, eager to find ways to separate immigrant children from those alien practices of their parents.

Munsterberg’s particular obsession lay in quantifying the mental and physical powers of the population for central government files, so policymakers could manage the nation’s "human resources" efficiently. His students became leaders of the "standardization" crusade in America. Munsterberg was convinced that racial differences could be reduced to numbers, equally convinced it was his sacred duty to the Aryan race to do so. Aryanism crackled like static electricity across the surface of American university life in those days, its implications part of every corporate board game and government bureau initiative.

One of Munsterberg’s favorite disciples, Lillian Wald, became a powerful advocate of medical incursions into public schools. The famous progressive social reformer wrote in 1905: "It is difficult to place a limit upon the service which medical inspection should perform,"1 continuing, "Is it not logical to conclude that physical development…should so far as possible be demanded?" One year later, immigrant public schools in Manhattan began performing tonsillectomies and adenoidectomies in school without notifying parents. The New York Times (June 29, 1906) reported that "Frantic Italians" — many armed with stilettos — "stormed" three schools, attacking teachers and dragging children from the clutches of the true believers into whose hands they had fallen. Think of the conscience which would ascribe to itself the right to operate on children at official discretion and you will know beyond a doubt what a true believer smells like.

Even a cursory study of the history of the school institution turns up true belief in rich abundance. In a famous book, The Proper Study of Mankind (1948), paid for by the Carnegie Corporation of New York and the Russell Sage Foundation, the favorite principle of true believers since Plato makes an appearance: "A society could be completely made over in something like 15 years, the time it takes to inculcate a new culture into a rising group of youngsters." Despite the spirit of profound violence hovering over such seemingly bloodless, abstract formulas, this is indeed the will-o-the-wisp pursued throughout the twentieth century in forced schooling — not intellectual development, not character development, but the inculcation of a new synthetic culture in children, one designed to condition its subjects to a continual adjusting of their lives by unseen authorities.

The Definition of a Pr...

Best Price: $5.95

Buy New $27.25

(as of 09:54 UTC - Details)

The Definition of a Pr...

Best Price: $5.95

Buy New $27.25

(as of 09:54 UTC - Details)

It’s true that numerically, only a small fraction of those who direct institutional schooling are actively aware of its ideological bent, but we need to see that without consistent generalship from that knowledgeable group in guiding things, the evolution of schooling would long ago have lost its coherence, degenerating into battles between swarms of economic and political interests fighting over the treasure-house that hermetic pedagogy represents. One of the hardest things to understand is that true believers — dedicated ideologues — are useful to all interests in the school stew by providing a salutary continuity to the enterprise.

Because of the predictable greed embedded in this culture, some overarching "guardian" vision, one indifferent to material gain, seems necessary to prevent marketplace chaos. True believers referee the school game, establishing its goals, rules, penalties; they negotiate and compromise with other stakeholders. And strangely enough, above all else, they can be trusted to continue being their predictable, dedicated, selfless selves. Pragmatic stakeholders need them to keep the game alive; true believers need pragmatists as cover. Consider this impossibly melodramatic if you must. I know myself that parts of my story sound like leaves torn from Ragtime. But from start to finish this is a tale of true believers and how by playing on their pipes they took all the children away.

The Prototype Is A Schoolteacher

One dependable signal of a true believer’s presence is a strong passion for everyone’s children. Find nonstop, abstract interest in the collective noun "children," the kind of love Pestalozzi or Froebel had, and you’ve flushed the priesthood from its lair. Eric Hoffer tells us the prototype true believer is a schoolteacher. Mao was a schoolteacher, so was Mussolini, so were many other prominent warlike leaders of our time, including Lyndon Johnson. In Hoffer’s characterization, the true believer is identified by inner fire, "a burning conviction we have a holy duty to others." Lack of humor is one touchstone of true belief.

The expression "true believer" is from a fifth-century book, The City of God, occurring in a passage where St. Augustine urges holy men and women to abandon fear and embrace their sacred work fervently. True Belief is a psychological frame you’ll find useful to explain individuals who relentlessly pursue a cause indifferent to personal discomfort, indifferent to the discomfort of others.2 All of us show a tiny element of true belief in our makeup, usually just enough to recognize the lunatic gleam in the eye of some purer zealot when we meet face to face. But in an age which distances us from hand-to-hand encounters with authority — removing us electronically, bureaucratically, and institutionally — the truly fanatical among us have been granted the luxury of full anonymity. We have to judge their presence by the fallout.

Horace Mann exemplifies the type. From start to finish he had a mission. He spoke passionately at all times. He wrote notes to himself about "breaking the bond of association among workingmen." In a commencement harangue at Antioch College in 1859, he said, "Be ashamed to die until you have won some victory for humanity." A few cynical critics snipe at Mann for lying about his imaginary school tour of Prussia (which led to the adoption of Prussian schooling methodologies in America), but those cynics miss the point. For the great ones, the goal is everything; the end justifies any means. Mann lived and died a social crusader. His second wife, Mary Peabody, paid him this posthumous tribute: "He was all afire with Purpose."

Al Shanker, longtime president of the American Federation of Teachers, said in one of his last Sunday advertisements in The New York Times before his death: "Public schools do not exist to please Johnny’s parents. They do not even exist to ensure that Johnny will one day earn a good living at a job he likes." No other energy but true belief can explain what Shanker might have had in mind.

Teachers College Maintains The Planet

A beautiful example of true belief in action crossed my desk recently from the alumni magazine of my own alma mater, Columbia University. Written by the director of Columbia’s Institute for Learning Technologies, a bureau at Teachers College, this mailing informed graduates that the education division now regarded itself as bound by "a contract with posterity." Something in the tone warned me against dismissing this as customary institutional gas. Seconds later I learned, with some shock, that Teachers College felt obligated to take a commanding role in "maintaining the planet." The next extension of this strange idea was even more pointed. Teachers College now interpreted its mandate, I was told, as one compelling it "to distribute itself all over the world and to teach every day, 24 hours a day."

To gain perspective, try to imagine the University of Berlin undertaking to distribute itself among the fifty American states, to be present in this foreign land twenty-four hours a day, swimming in the minds of Mormon children in Utah and Baptist children in Georgia. Any university intending to become global like some nanny creature spawned in Bacon’s ghastly utopia, New Atlantis, is no longer simply in the business of education. Columbia Teachers College had become an aggressive evangelist by its own announcement, an institution of true belief selling an unfathomable doctrine. I held its declaration in my hand for a while after I read it. Thinking.

Angelau2019s Ashes: A ...

Best Price: Too low to display

Buy New $4.95

(as of 10:41 UTC - Details)

Angelau2019s Ashes: A ...

Best Price: Too low to display

Buy New $4.95

(as of 10:41 UTC - Details)

Let me underline what you just heard. Picture some U.N. thought police dragging reluctant Serbs to a loudspeaker to listen to Teachers College rant. Most of us have no frame of reference in which to fit such a picture. Narcosis in the face of true belief is a principal reason the disease progressed so far through the medium of forced schooling without provoking much major opposition. Only after a million homeschooling families and an equal number of religiously oriented private-school families emerged from their sleep to reclaim their children from the government in the 1970s and 1980s, in direct response to an epoch of flagrant social experimentation in government schools, did true belief find ruts in its road.

Columbia, where I took an undergraduate degree, is the last agency I would want maintaining my planet. For decades it was a major New York slumlord indifferent to maintaining its own neighborhood, a territory much smaller than the globe. Columbia has been a legendary bad neighbor to the community for the forty years I’ve lived near my alma mater. So much for its qualifications as Planetary Guardian. Its second boast is even more ominous — I mean that goal of intervening in mental life "all over the world," teaching "every day, 24 hours a day." Teaching what? Shouldn’t we ask? Our trouble in recognizing true belief is that it wears a reasonable face in modern times.

A Lofty, Somewhat Inhuman Vision

Take a case reported by the Public Agenda Foundation which produced the first-ever survey of educational views held by teachers college professors. To their surprise, the authors discovered that the majority of nine hundred randomly selected professors of education interviewed did not regard a teacher’s struggle to maintain an orderly classroom or to cope with disruptive students as major problems! The education faculty was generally unwilling to attend to these matters seriously in their work, believing that widespread alarm among parents stemming from worry that graduates couldn’t spell, couldn’t count accurately, couldn’t sustain attention, couldn’t write grammatically (or write at all) was only caused by views of life "outmoded and mistaken."

While 92 percent of the public thinks basic reading, writing, and math competency is "absolutely essential" (according to an earlier study by Public Agenda), education professors did not agree. In the matter of mental arithmetic, which a large majority of ordinary people, including some schoolteachers, consider very important, about 60 percent of education professors think cheap calculators make that goal obsolete.

The word passion appears more than once in the report from which these data are drawn, as in the following passage:

Education professors speak with passionate idealism about their own, sometimes lofty, vision of education and the mission of teacher education programs. The passion translates into ambitious and highly-evolved expectations for future teachers, expectations that often differ dramatically from those of parents and teachers now in the classroom. "The soul of a teacher is what should be passed on from teacher to teacher," a Boston professor said with some intensity. "You have to have that soul to be a good teacher."

It’s not my intention at this moment to recruit you to one or another side of this debate, but only to hold you by the back of the neck as Uncle Bud (who you’ll meet up ahead) once held mine and point out that this vehicle has no brake pedal — ordinary parents and students have no way to escape this passion. Twist and turn as they might, they will be subject to any erotic curiosity inspired love arouses. In the harem of true belief, there is scant refuge from the sultan’s lusty gaze.

Rain Forest Algebra

In the summer of 1997, a Democratic senator stood on the floor of the Senate denouncing the spread of what he called "wacko algebra"; one widely distributed math text referred to in that speech did not ask a question requiring algebraic knowledge until page 107. What replaced the boredom of symbolic calculation were discussions of the role of zoos in community life, or excursions to visit the fascinating Dogon tribe of West Africa. Whatever your own personal attitude toward "rain forest algebra," as it was snidely labeled, you would be hard-pressed not to admit one thing: its problems are almost computation-free. Whether you find the mathematical side of social issues relevant or not isn’t in question. Your attention should be fixed on the existence of minds, nominally in charge of number enlightenment for your children, which consider a private agenda more important than numbers.

One week last spring, the entire math homework in fifth grade at middle-class P.S. 87 on the Upper West Side of Manhattan consisted of two questions:3

- Historians estimate that when Columbus landed on what is now the island of Hati [this is the spelling in the question] there were 250,000 people living there. In two years this number had dropped to 125,000. What fraction of the people who had been living in Hati when Columbus arrived remained? Why do you think the Arawaks died?

- In 1515 there were only 50,000 Arawaks left alive. In 1550 there were 500. If the same number of people died each year, approximately how many people would have died each year? In 1550 what percentage of the original population was left alive? How do you feel about this?

Tom Loveless, professor at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard, has no doubt that National Council of Teachers of Mathematics standards have deliberately de-emphasized math skills, and he knows precisely how it was done. But like other vigorous dissenters who have tried to arrest the elimination of critical intellect in children, he adduces no motive for the awesome project which has worked so well up to now. Loveless believes that the "real reform project has begun: writing standards that declare the mathematics children will learn." He may be right, but I am not so sanguine.

Elsewhere there are clues which should check premature optimism. In 1989, according to Loveless, a group of experts in the field of math education launched a campaign "to change the content and teaching of mathematics." This new math created state and district policies which "tend to present math reform as religion" and identify as sinful behaviors teacher-delivered instruction, individual student desk work, papers corrected for error. Teachers are ordered to keep "an elaborate diary on each child’s ‘mathematical disposition.’"

Specific skills de-emphasized are: learning to use fractions, decimals, percents, integers, addition, subtraction, multiplication, division — all have given way to working with manipulatives like beans and counting sticks (much as the Arawaks themselves would have done) and with calculators. Parents worry themselves sick when fifth graders can’t multiply 7 times 5 without hunting for beans and sticks. Students who learn the facts of math deep down in the bone, says Loveless, "gain a sense of number unfathomable to those who don’t know them."

The question critics should ask has nothing to do with computation or reading ability and everything to do with this: How does a fellow human being come to regard ordinary people’s children as experimental animals? What impulse triggers the pornographic urge to deprive kids of volition, to fiddle with their lives? It is vital that you consider this or you will certainly fall victim to appeals that you look at the worthiness of the outcomes sought and ignore the methods. This appeal to pragmatism urges a repudiation of principle, sometimes even on the grounds that modern physics "proves" there is no objective reality.

Whether children are better off or not being spared the effort of thinking algebraically may well be a question worth debating but, if so, the burden of proof rests on the challenger. Short-circuiting the right to choice is a rapist’s tactic or a seducer’s. If, behind a masquerade of number study, some unseen engineer infiltrates the inner layers of a kid’s consciousness — the type of subliminal influence exerted in rain forest algebra — tinkering with the way a child sees the larger world, then in a literal sense the purpose of the operation is to dehumanize the experimental subject by forcing him or her into a predetermined consensus.

Godless, But Not Irreligious

True believers are only one component of American schooling, as a fraction probably a small one, but they constitute a tail that wags the dog because they possess a blueprint and access to policy machinery, while most of the rest of us do not. The true believers we call great educators — Komensky, Mather, Pestalozzi, Froebel, Mann, Dewey, Sears, Cubberley, Thorndike, et al. — were ideologues looking for a religion to replace one they never had or had lost faith in. As an abstract type, men like this have been analyzed by some of the finest minds in the history of modern thought — Machiavelli, Tocqueville, Renan, William James to name a few — but the clearest profile of the type was set down by Eric Hoffer, a one-time migrant farm worker who didn’t learn to read until he was fifteen years old. In The True Believer, a luminous modern classic, Hoffer tells us:

Though ours is a godless age, it is the very opposite of irreligious. The true believer is everywhere on the march, shaping the world in his own image. Whether we line up with him or against him, it is well we should know all we can concerning his nature and potentialities.

Homeschooling at the S...

Best Price: $3.47

Buy New $9.01

(as of 11:05 UTC - Details)

Homeschooling at the S...

Best Price: $3.47

Buy New $9.01

(as of 11:05 UTC - Details)

It looks to me as if the energy to run this train was released in America from the stricken body of New England Calvinism when its theocracy collapsed from indifference, ambition, and the hostility of its own children. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, shortly after we became a nation, this energy gave rise to what Allan Bloom dubbed "the new American religion," eventually combining elements of old Calvinism with flavors of Anabaptism, Ranting, Leveling, Quakerism, rationalism, positivism, and that peculiar Unitarian spice: scientism.4

Where the parent form of American Calvinism had preached the rigorous exclusion of all but a tiny handful deemed predestinated for salvation (the famous "Saints" or "justified sinners"), the descendant faith, beginning about the time of the Great Awakening of the 1740s, demanded universal inclusion, recruitment of everyone into a universal, unitarian salvation — whether they would be so recruited or not. It was a monumental shift which in time infiltrated every American institution. In its demand for eventual planetary unity the operating logic of this hybrid religion, which derived from a medley of Protestant sects as well as from Judaism, in a cosmic irony was intensely Catholic right down to its core.

After the Unitarian takeover of Harvard in 1805, orthodox Calvinism seemingly reached the end of its road, but so much explosive energy had been tightly bound into this intense form of sacred thought — an intensity which made every act, however small, brim with significance, every expression of personality proclaim an Election or Damnation — that in its structural collapse, a ferocious energy was released, a tornado that flashed across the Burned Over District of upstate New York, crossing the lakes to Michigan and other Germanized outposts of North America, where it split suddenly into two parts — one racing westward to California and the northwest territories, another turning southwest to the Mexican colony called Texas. Along the way, Calvin’s by now much-altered legacy deposited new religions like Mormonism and Seventh Day Adventism, raised colleges like the University of Michigan and Michigan State (which would later become fortresses of the new schooling religion) and left prisons, insane asylums, Indian reservations, and poorhouses in its wake as previews of the secularized global village it aimed to create.

School was to be the temple of a new, all-inclusive civil religion. Calvinism had stumbled, finally, from being too self-contained. This new American form, learning from Calvinism’s failure, aspired to become a multicultural super-system, world-girdling in the fullness of time. Our recent military invasions of Haiti, Panama, Iraq, the Balkans, and Afghanistan, redolent of the palmy days of British empire, cannot be understood from the superficial justifications offered. Yet, with an eye to Calvin’s legacy, even foreign policy yields some of its secret springs. Calvinist origins armed school thinkers from the start with a utilitarian contempt for the notion of free will.

Brain-control experiments being explored in the psychophysical labs of northern Germany in the last quarter of the nineteenth century attracted rich young men from thousands of prominent American families. Such mind science seemed to promise that tailor-made technologies could emerge to shape and control thought, technologies which had never existed before. Children, the new psychologies suggested, could be emptied, denatured, then reconstructed to more accommodating designs. H.G. Wells’ Island of Dr. Moreau was an extrapolation-fable based on common university-inspired drawing room conversations of the day.

David Hume’s empirical philosophy, working together with John Locke’s empiricism, had prepared the way for social thinkers to see children as blank slates — an opinion predominant among influentials long before the Civil War and implicit in Machiavelli, Bodin, and the Bacons. German psychophysics and physiological psychology seemed a wonderful manufactory of the tools a good political surgeon needed to remake the modern world. Methods for modifying society and all its inhabitants began to crystallize from the insights of the laboratory. A good living could be made by saying it was so, even if it weren’t true. When we examine the new American teacher college movement at the turn of this century we discover a resurrection of the methodology of Prussian philosopher Herbart well underway. Although Herbart had been dead a long time by then, he had the right message for the new age. According to Herbart, "Children should be cut to fit."

An Insider’s Insider

A bountiful source of clues to what tensions were actually at work back then can be found in Ellwood P. Cubberley’s celebratory history, Public Education in the United States (1919, revised edition 1934), the standard in-house reference for official school legends until revisionist writings appeared in the 1960s.

Cubberley was an insider’s insider, in a unique position to know things neither public nor press could know. Although Cubberley always is circumspect and deliberately vague, he cannot help revealing more than he wants to. For example, the reluctance of the country to accept its new yoke of compulsion is caught briefly in this flat statement on page 564 of the 1934 revision:

The history of compulsory-attendance legislation in the states has been much the same everywhere, and everywhere laws have been enacted only after overcoming strenuous opposition.

Reference here is to the period from 1852 to 1918 when the states, one by one, were caught in a compulsion net that used the strategy of gradualism:

At first the laws were optional…later the law was made state-wide but the compulsory period was short (ten to twelve weeks) and the age limits low, nine to twelve years. After this, struggle came to extend the time, often little by little…to extend the age limits downward to eight and seven and upwards to fourteen, fifteen or sixteen; to make the law apply to children attending private and parochial schools, and to require cooperation from such schools for the proper handling of cases; to institute state supervision of local enforcement; to connect school attendance enforcement with the child-labor legislation of the State through a system of working permits…. [emphasis added]

Noteworthy is the extent to which proponents of centralized schooling were prepared to act covertly in defiance of majority will and in the face of extremely successful and inexpensive local school heritage. As late as 1901, after nearly a half-century of such legislation — first in Massachusetts, then state by state in the majority of the remaining jurisdictions — Dr. Levi Seeley of Trenton Normal School could still thunder warnings of lack of progress. In his book Foundations of Education, he writes, "while no law on the statute books of Prussia is more thoroughly carried out [than compulsory attendance]…" He laments that "…in 1890, out of 5,300,000 Prussian children, only 645 slipped out of the truant officer’s net…" but that our own school attendance legislation is nothing more than "dead letter laws":

We have been attempting compulsory education for a whole generation and cannot be said to have made much progress — Let us cease to require only 20 weeks of schooling, 12 of which shall be consecutive, thus plainly hinting that we are not serious in the matter.

Seeley’s frustration clouded his judgment. Somebody was most certainly serious about mass confinement schooling to stay at it so relentlessly and expensively in the face of massive public repudiation of the scheme.

Compulsion Schooling

The center of the scheme was Massachusetts, the closest thing to a theocracy to have emerged in America. The list below is a telling record of the long gap between the Massachusetts compulsory law of 1852 and similar legislation adopted by the next set of states. Instructive also in the chronology is the place taken by the District of Columbia, the seat of federal government.

Compulsory School Legislation

1852 Massachusetts ![]() 1875 Maine 1865 District of Columbia New Jersey 1867 Vermont 1876 Wyoming Territory 1871 New Hampshire 1877 Ohio Washington Territory 1879 Wisconsin 1872 Connecticut 1883 Rhode Island New Mexico Territory Illinois 1873 Nevada Dakota Territory 1874 New York Montana Territory Kansas California

1875 Maine 1865 District of Columbia New Jersey 1867 Vermont 1876 Wyoming Territory 1871 New Hampshire 1877 Ohio Washington Territory 1879 Wisconsin 1872 Connecticut 1883 Rhode Island New Mexico Territory Illinois 1873 Nevada Dakota Territory 1874 New York Montana Territory Kansas California

Six other Western states and territories were added by 1890. Finally in 1918, sixty-six years after the Massachusetts force legislation, the forty-eighth state, Mississippi, enacted a compulsory school attendance law. Keep in mind Cubberley’s words: everywhere there was "strenuous opposition."

De-Moralizing School Procedure

But a strange thing happened as more and more children were drawn into the net, a crisis of an unexpected sort. At first those primitive one-room and two-room compulsion schools — even the large new secondary schools like Philadelphia’s Central High — poured out large numbers of trained, disciplined intellects. Government schoolteachers in those early days chose overwhelmingly to emulate standards of private academies, and to a remarkable degree they succeeded in unwittingly sabotaging the hierarchical plan being moved on line. Without a carefully trained administrative staff (and most American schools had no administrators), it proved impossible to impose the dumbing-down process5 promised by the German prototype. In addition, right through the 1920s, a skilled apprenticeship alternative was active in the United States, traditional training that still honored our national mythology of success.

Dumbing Us Down: The H...

Best Price: $1.48

Buy New $15.59

(as of 03:50 UTC - Details)

Dumbing Us Down: The H...

Best Price: $1.48

Buy New $15.59

(as of 03:50 UTC - Details)

Ironically, the first crisis provoked by the new school institution was taking its rhetorical mandate too seriously. From it poured an abundance of intellectually trained minds at exactly the moment when the national economy of independent livelihoods and democratic workplaces was giving way to professionally managed, accountant-driven hierarchical corporations which needed no such people. The typical graduate of a one-room school represented a force antithetical to the logic of corporate life, a cohort inclined to judge leadership on its merit, one reluctant to confer authority on mere titles.6

Immediate action was called for. Cubberley’s celebratory history doesn’t examine motives, but does uneasily record forceful steps taken just inside the new century to nip the career of intellectual schooling for the masses in the bud, replacing it with a different goal: the forging of "well-adjusted" citizens.

Since 1900, and due more to the activity of persons concerned with social legislation and those interested in improving the moral welfare of children than to educators themselves, there has been a general revision of the compulsory education laws of our States and the enactment of much new child-welfare…and anti-child-labor legislation…. These laws have brought into the schools not only the truant and the incorrigible, who under former conditions either left early or were expelled, but also many children…who have no aptitude for book learning and many children of inferior mental qualities who do not profit by ordinary classroom procedures…. Our schools have come to contain many children who…become a nuisance in the school and tend to demoralize school procedure. [emphasis added]

We’re not going to get much closer to running face-to-face into the true believers and the self-interested parties who imposed forced schooling than in Cubberley’s mysterious "persons concerned with social legislation." At about the time Cubberley refers to, Walter Jessup, president of the University of Iowa, was publicly complaining, "Now America demands we educate the whole…. It is a much more difficult problem to teach all children than to teach those who want to learn."

Common sense should tell you it isn’t "difficult" to teach children who don’t want to learn. It’s impossible. Common sense should tell you "America" was demanding nothing of the sort. But somebody most certainly was insisting on universal indoctrination in class subordination. The forced attendance of children who want to be elsewhere, learning in a different way, meant the short happy career of academic public schooling was deliberately foreclosed, with "democracy" used as the excuse. The new inclusive pedagogy effectively doomed the bulk of American children.

What you should take away from this is the deliberate introduction of children who "demoralize school procedure," children who were accommodated prior to this legislation in a number of other productive (and by no means inferior) forms of training, just as Benjamin Franklin had been. Richard Hofstadter and other social historians have mistakenly accepted at face value official claims that "democratic tradition" — the will of the people — imposed this anti-intellectual diet on the classroom. Democracy had nothing to do with it.

What we are up against is a strategic project supported by an uneasy coalition of elites, each with its own private goals in mind for the common institution. Among those goals was the urge to go to war against diversity, to impose orthodoxy on heterodox society. For an important clue to how this was accomplished we return to Cubberley:

The school reorganized its teaching along lines dictated by the new psychology of instruction which had come to us from abroad…. Beginning about 1880 to 1885 our schools began to experience a new but steady change in purpose [though] it is only since about 1900 that any marked and rapid changes have set in.

The new psychology of instruction cited here is the new experimental psychology of Wilhelm Wundt at Leipzig, which dismissed the very existence of mind as an epiphenomenon. Children were complex machines, capable of infinite "adjustments." Here was the beginning of that new and unexpected genus of schooling which Bailyn said "troubled well-disposed, high-minded people," and which elevated a new class of technocrat like Cubberley and Dewey to national prominence. The intention to sell schooling as a substitute for faith is caught clearly in Cubberley’s observation: "However much we may have lost interest in the old problems of faith and religion, the American people have come to believe thoroughly in education." New subjects replaced "the old limited book subject curriculum, both elementary and secondary."

This was done despite the objections of many teachers and citizens, and much ridicule from the public press. Many spoke sneeringly of the new subjects.

Cubberley provides an accurate account of the prospective new City on the Hill for which "public education" was to be a prelude, a City which rose hurriedly after the failed populist revolt of 1896 frightened industrial leaders. I’ve selected six excerpts from Cubberley’s celebrated History which allow you to see, through an insider’s eyes, the game that was afoot a century ago as U.S. school training was being fitted for its German uniform. (All emphasis in the list that follows is my own):

- The Spanish-American War of 1898 served to awaken us as a nation…It revealed to us something of the position we should be called on to occupy in world affairs….

- For the two decades following…. the specialization of labor and the introduction of labor-saving machinery took place to an extent before unknown…. The national and state government were called upon to do many things for the benefit of the people never attempted before.

- Since 1898, education has awakened a public interest before unknown…. Everywhere state educational commissions and city school surveys have evidenced a new critical attitude…. Much new educational legislation has been enacted; permission has been changed to obligation; minimum requirements have been laid down by the States in many new directions; and new subjects of instruction have been added by the law. Courses of study have been entirely made over and new types of textbooks have appeared….. A complete new system of industrial education, national in scope, has been developed.

- New normal schools have been founded and higher requirements have been ordered for those desiring to teach. College departments of education have increased from eleven in 1891 to something like five hundred today [1919]. Private gifts to colleges and universities have exceeded anything known before in any land. School taxes have been increased, old school funds more carefully guarded, and new constitutional provisions as to education have been added.

- Compulsory education has begun to be a reality, and child-labor laws to be enforced.

- A new interest in child-welfare and child-hygiene has arisen, evidencing commendable desire to look after the bodies as well as the minds of children….

Here in a brief progression is one window on the problem of modern schooling. It set out to build a new social order at the beginning of the twentieth century (and by 1970 had succeeded beyond all expectations), but in the process it crippled the democratic experiment of America, disenfranchising ordinary people, dividing families, creating wholesale dependencies, grotesquely extending childhoods. It emptied people of full humanity in order to convert them into human resources.

William Torrey Harris

If you have a hard time believing that this revolution in the contract ordinary Americans had with their political state was intentionally provoked, it’s time for you to meet William Torrey Harris, U.S. Commissioner of Education from 1889 to 1906. No one, other than Cubberley, who rose out of the ranks of professional pedagogues ever had as much influence as Harris. Harris both standardized and Germanized our schools. Listen to his voice from The Philosophy of Education, published in 1906:

Ninety-nine [students] out of a hundred are automata, careful to walk in prescribed paths, careful to follow the prescribed custom. This is not an accident but the result of substantial education, which, scientifically defined, is the subsumption of the individual. ~ The Philosophy of Education (1906)

Listen to Harris again, giant of American schooling, leading scholar of German philosophy in the Western hemisphere, editor and publisher of The Journal of Speculative Philosophy which trained a generation of American intellectuals in the ideas of the Prussian thinkers Kant and Hegel, the man who gave America scientifically age-graded classrooms to replace successful mixed-age school practice. Again, from The Philosophy of Education, Harris sets forth his gloomy vision:

The great purpose of school can be realized better in dark, airless, ugly places…. It is to master the physical self, to transcend the beauty of nature. School should develop the power to withdraw from the external world. ~ The Philosophy of Education (1906)

Nearly a hundred years ago, this schoolman thought self-alienation was the secret to successful industrial society. Surely he was right. When you stand at a machine or sit at a computer you need an ability to withdraw from life, to alienate yourself without a supervisor. How else could that be tolerated unless prepared in advance by simulated Birkenhead drills? School, thought Harris, was sensible preparation for a life of alienation. Can you say he was wrong?

Home Learning Year by ...

Best Price: $1.48

Buy New $6.49

(as of 01:35 UTC - Details)

Home Learning Year by ...

Best Price: $1.48

Buy New $6.49

(as of 01:35 UTC - Details)

In exactly the years Cubberley of Stanford identified as the launching time for the school institution, Harris reigned supreme as the bull goose educator of America. His was the most influential voice teaching what school was to be in a modern, scientific state. School histories commonly treat Harris as an old-fashioned defender of high academic standards, but this analysis is grossly inadequate. Stemming from his philosophical alignment with Hegel, Harris believed that children were property and that the state had a compelling interest in disposing of them as it pleased. Some would receive intellectual training, most would not. Any distinction that can be made between Harris and later weak curriculum advocates (those interested in stupefaction for everybody) is far less important than substantial agreement in both camps that parents or local tradition could no longer determine the individual child’s future.

Unlike any official schoolman until Conant, Harris had social access to important salons of power in the United States. Over his long career he furnished inspiration to the ongoing obsessions of Andrew Carnegie, the steel man who first nourished the conceit of yoking our entire economy to cradle-to-grave schooling. If you can find copies of The Empire of Business (1902) or Triumphant Democracy (1886), you will find remarkable congruence between the world Carnegie urged and the one our society has achieved.

Carnegie’s "Gospel of Wealth" idea took his peers by storm at the very moment the great school transformation began — the idea that the wealthy owed society a duty to take over everything in the public interest, was an uncanny echo of Carnegie’s experience as a boy watching the elite establishment of Britain and the teachings of its state religion. It would require perverse blindness not to acknowledge a connection between the Carnegie blueprint, hammered into shape in the Greenwich Village salon of Mrs. Botta after the Civil War, and the explosive developments which restored the Anglican worldview to our schools.

Of course, every upper class in history has specified what can be known. The defining characteristic of class control is its establishment of a grammar and vocabulary for ordinary people, and for subordinate elites, too. If the rest of us uncritically accept certain official concepts such as "globalization," then we have unwittingly committed ourselves to a whole intricate narrative of society’s future, too, a narrative which inevitably drags an irresistible curriculum in its wake.

Since Aristotle, thinkers have understood that work is the vital theater of self-knowledge. Schooling in concert with a controlled workplace is the most effective way to foreclose the development of imagination ever devised. But where did these radical doctrines of true belief come from? Who spread them? We get at least part of the answer from the tantalizing clue Walt Whitman left when he said "only Hegel is fit for America." Hegel was the protean Prussian philosopher capable of shaping Karl Marx on one hand and J.P. Morgan on the other; the man who taught a generation of prominent Americans that history itself could be controlled by the deliberate provoking of crises. Hegel was sold to America in large measure by William Torrey Harris, who made Hegelianism his lifelong project and forced schooling its principal instrument in its role as an unrivaled agent provocateur.

Harris was inspired by the notion that correctly managed mass schooling would result in a population so dependent on leaders that schism and revolution would be things of the past. If a world state could be cobbled together by Hegelian tactical manipulation, and such a school plan imposed upon it, history itself would stop. No more wars, no civil disputes, just people waiting around pleasantly like the Eloi in Wells’ The Time Machine. Waiting for Teacher to tell them what to do. The psychological tool was alienation. The trick was to alienate children from themselves so they couldn’t turn inside for strength, to alienate them from their families, religions, cultures, etc., so that no countervailing force could intervene.

Carnegie used his own considerable influence to keep this expatriate New England Hegelian the U.S. Commissioner of Education for sixteen years, long enough to set the stage for an era of "scientific management" (or "Fordism" as the Soviets called it) in American schooling. Long enough to bring about the rise of the multilayered school bureaucracy. But it would be a huge mistake to regard Harris and other true believers as merely tools of business interests; what they were about was the creation of a modern living faith to replace the Christian one which had died for them. It was their good fortune to live at precisely the moment when the dreamers of the empire of business (to use emperor Carnegie’s label) for an Anglo-American world state were beginning to consider worldwide schooling as the most direct route to that destination.

Both movements, to centralize the economy and to centralize schooling, were aided immeasurably by the rapid disintegration of old-line Protestant churches and the rise from their pious ashes of the "Social Gospel" ideology, aggressively underwritten by important industrialists, who intertwined church-going tightly with standards of business, entertainment, and government. The experience of religion came to mean, in the words of Reverend Earl Hoon, "the best social programs money can buy." A clear statement of the belief that social justice and salvation were to be had through skillful consumption.

Shailer Mathews, dean of Chicago’s School of Divinity, editor of Biblical World, president of the Federal Council of Churches, wrote his influential Scientific Management in the Churches (1912) to convince American Protestants they should sacrifice independence and autonomy and adopt the structure and strategy of corporations:

If this seems to make the Church something of a business establishment, it is precisely what should be the case.

If Americans listened to the corporate message, Mathews told them they would feel anew the spell of Jesus.

In the decade before WWI, a consortium of private foundations drawing on industrial wealth began slowly working toward a long-range goal of lifelong schooling and a thoroughly rationalized global economy and society.

Cardinal Principles

Frances Fitzgerald, in her superb study of American textbooks, America Revised, notes that schoolbooks are superficial and mindless, that they deliberately leave out important ideas, that they refuse to deal with conflict — but then she admits to bewilderment. What could the plan be behind such texts? Is the composition of these books accidental or deliberate?

Sidestepping an answer to her own question, Fitzgerald traces the changeover to a pair of influential NEA reports published in 1911 and 1918 which reversed the scholarly determinations of the blue-ribbon "Committee of Ten" report of 1893. That committee laid down a rigorous academic program for all schools and for all children, giving particular emphasis to history. It asserted, "The purpose of all education is to train the mind." The NEA reports of 1911 and 1918 denote a conscious abandonment of this intellectual imperative and the substitution of some very different guiding principles. These statements savagely attack "the bookish curricula" which are "responsible for leading tens of thousands of boys and girls away from pursuits for which they are adapted," toward pursuits for which they are not — like independent businesses, invention, white collar work, or the professions.

Books give children "false ideals of culture." These reports urged the same kinds of drill which lay at the core of Prussian commoner schools. An interim report of 1917 also proposes that emphasis be shifted away from history to something safer called "social studies"; the thrust was away from any careful consideration of the past so that attention might be focused on the future. That 1918 NEA Report, Cardinal Principles of Secondary Education, for all its maddening banality, was to prove over time one of the most influential education documents of the twentieth century. It decreed that specified behaviors, health, and vocational training were the central goals of education, not mental development, not character, not godliness.

Fitzgerald wrote she could not find a name for "the ideology that lies behind these texts." The way they handle history, for instance, is not history at all, "but a catechism… of American socialist realism." More than once she notes "actual hostility to the notion of intellectual training." Passion, in partnership with impatience for debate, is one good sign of the presence of true belief.

The most visible clue to the degree true belief was at work in mass schooling in the early decades of this century is the National Education Association’s 1918 policy document. Written entirely in the strangely narcotic diction and syntax of official pedagogy, which makes it almost impenetrable to outsiders, Cardinal Principles announced a new de-intellectualized curriculum to replace the famous recipe for high goals and standards laid out three decades earlier by the legendary Committee of Ten, which declared the purpose of all education to be the training of the mind.

This new document contradicted its predecessor. In a condemnation worth repeating, it accused that older testament of forcing impossible intellectual ambitions on common children, of turning their empty heads, giving them "false ideals of culture." The weight of such statements, full of assumptions and implications, cannot easily be felt through its abstract language, but if you recognize that its language conceals a mandate for the mass dumbing down of young Americans, then some understanding of the magnitude of the successful political coup which had occurred comes through to penetrate the fog. The repudiation of the Committee of Ten was reinforced by a companion report proposing that history, economics, and geography be dropped at once.

What Cardinal Principles gave proof of was that stage one of a silent revolution in American society was complete. Children could now be taught anything, or even taught nothing in the part-time prisons of schooling, and there was little any individual could do about it. Bland generalities in the document actually served as potent talismans to justify the engineering of stupefaction. Local challenges could be turned back, local challengers demonized and marginalized, just by waving the national standards of Cardinal Principles as proof of one’s legitimacy.

Venal motives as well as ideological ones were served by the comprehensive makeover of schooling, and palms incidentally greased in the transition soon found themselves defending it for their own material advantage. Schools quickly became the largest jobs project in the country, an enormous contractor for goods and services, one always willing to pay top dollar for bottom-shelf merchandise in a dramatic reversal of economic theory. There are no necessary economies in large- scale purchasing;7 school is proof of that.

Cardinal Principles assured mass production technocrats they would not have to deal with intolerable numbers of independent thinkers — thinkers stuffed with dangerous historical comparisons, who understood economics, who had insight into human nature through literary studies, who were made stoical or consensus-resistant by philosophy and religion, and given confidence and competence through liberal doses of duty, responsibility, and experience.

The appearance of Cardinal Principles signaled the triumph of forces which had been working since the 1890s to break the hold of complex reading, debate, and writing as the common heritage of children reared in America. Like the resourcefulness and rigors of character that small farming conveyed, complex and active literacy produces a kind of character antagonistic to hierarchical, expert-driven, class-based society. As the nature of American society was moved deliberately in this direction, forges upon which a different kind of American had been hammered were eliminated. We see this process nearly complete in the presentation of Cardinal Principles.

We always knew the truth in America, that almost everyone can learn almost anything or be almost anything. But the problem with that insight is that it can’t co-exist with any known form of modern social ordering. Each species of true belief expresses some social vision or another, some holy way to arrange relationships, time, values, etc., in order to drive toward a settlement of the great question, "Why are we alive?" The trouble with a society which encourages argument, as America’s did until the mid-twentieth century, is that there is no foreseeable end to the argument. No way to lock the door and announce that your own side has finally won. No certainty.

Our most famous true believers, the Puritans, thought they could build a City on the Hill and keep the riffraff out. When it became obvious that exclusion wasn’t going to work, their children and grandchildren did an about-face and began to move toward a totally inclusive society (though not a free one). It would be intricately layered into social classes like the old British system. This time God’s will wouldn’t be offered as reason for the way things were arranged by men. This time Science and Mathematics would justify things, and children would be taught to accept the inevitability of their assigned fates in the greatest laboratory of true belief ever devised: the Compulsion Schoolhouse.

The Unspeakable Chautauqua

One man left us a dynamic portrait of the great school project prematurely completed in miniature: William James, an insider’s insider, foremost (and first) psychologist of America, brother of novelist Henry James. James’ prestige as a most formidable Boston brahmin launched American psychology. Without him it’s touch and go whether it would have happened at all. His Varieties of Religious Experience is unique in the American literary canon; no wonder John Dewey dropped Hegel and Herbart after a brief flirtation with the Germans and attached himself to James and his philosophy of pragmatism (which is the Old Norse religion brought up to date). But James was too deep a thinker to believe his own screed fully. In a little book called Talks to Teachers, which remains in print today, over a hundred years after it was written, James disclosed his ambivalence about the ultimate dream of schooling in America.

It was no Asiatic urge to enslave, no Midas fantasy of unlimited wealth, no conspiracy of class warfare but only the dream of a comfortable, amusing world for everyone, the closest thing to an Augustan pastoral you could imagine — the other side of the British Imperial coin. England’s William Morris and John Ruskin and perhaps Thomas Carlyle were the literary godfathers of this dream society to come, a society already realized in a few cloistered spots on earth, on certain great English estates and at the mother center of the Chautauqua movement in western New York.

In 1899, James spoke to an idealistic new brigade of teachers recruited by Harvard, men and women meant to inspirit the new institution then rising swiftly from the ashes of the older neighborhood schools, private schools, church schools, and home schools. He spoke to the teachers of the dream that the entire planet could be transformed into a vast Chautauqua. Before you hear what he had to say, you need to know a little about Chautauqua.

On August 10, 1878, John H. Vincent announced his plan for the formation of a study group to undertake a four-year program of guided reading for ordinary citizens. The Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle signed up two hundred people its first hour, eighty-four hundred by year’s end. Ten years later, enrollment had grown to one hundred thousand. At least that many more had completed four years or fallen out after trying. In an incredibly short period of time every community in the United States had somebody in it following the Chautauqua reading program. One of its teachers, Melvil Dewey, developed the Dewey Decimal System still in use in libraries.

The reading list was ambitious. It included Green’s Short History of the English People, full of specific information about the original Anglo-Saxon tribes and their child-rearing customs — details which proved strikingly similar to the habits of upper-class Americans. Another Chautauqua text, Mahaffey’s Old Greek Life, dealt with the utopia of Classical Greece. It showed how civilization could only rise on the backs of underclass drudges. Many motivations to "Go Chautauqua" existed: love of learning, the social urge to work together, the thrill of competition in the race for honorary seals and diplomas which testified to a course completed, the desire to keep up with neighbors.

The Chautauqua movement gave settlers of the Midwest and Far West a common Anglo-German intellectual heritage to link up with. This grassroots vehicle of popular education offered illustrations of principles to guide anyone through any difficulty. And in Chautauqua, New York itself, at the Mother Center, a perfect jewel of a rational utopia was taking shape, attended by the best and brightest minds in American society. You’ll see it in operation just ahead with its soda pop fountains and model secondary schools.

The great driving force behind Chautauqua in its early years was William Rainey Harper, a Yale graduate with a Ph.D. in philology, a man expert in ancient Hebrew, a prominent Freemason. Harper attracted a great deal of attention in his Chautauqua tenure. He would have been a prominent name on the national scene for that alone, even without his connection to the famous publishing family.

Government Schools Are...

Best Price: $3.96

Buy New $4.99

(as of 09:05 UTC - Details)

Government Schools Are...

Best Price: $3.96

Buy New $4.99

(as of 09:05 UTC - Details)

John Vincent, Chautauqua’s founder, had been struck by the vision of a world college described in Bacon’s utopia, one crowded and bustling with international clientele and honored names as faculty. "Chautauqua will exalt the profession of teacher until the highest genius, the richest scholarship, and the broadest manhood and womanhood of the nation are consecrated to this service," Vincent once said. His explanation of the movement:

We expect the work of Chautauqua will be to arouse so much interest in the subject of general liberal education that by and by in all quarters young men and women will be seeking means to obtain such education in established resident institutions…. Our diploma, though radiant with thirty-one seals — shields, stars, octagons — would not stand for much at Heidelberg, Oxford, or Harvard…an American curiosity…. It would be respected not as conferring honor upon its holder, but as indicating a popular movement in favor of higher education.

Chautauqua’s leaders felt their institution was a way station in America’s progress to something higher. By 1886 Chautauqua was well-known all over. The new University of Chicago, which Harper took over five years later, was patterned on the Chautauqua system, which in turn was superimposed over the logic of the German research university. Together with Columbia Teachers College, Yale, Michigan, Wisconsin, Stanford, and a small handful of others, Chicago would provide the most important visible leadership for American public school policy well into the twentieth century.

At the peak of its popularity, eight thousand American communities subscribed to Chautauqua’s programmatic evangelism. The many tent-circuit Chautauquas simultaneously operating presented locals with the latest ideas in social progress, concentrating on self-improvement and social betterment through active Reform with a capital "R." But in practice, entertainment often superseded educational values because the temptation to hype the box-office draw was insidious. Over time, Progress came to be illustrated dramatically for maximum emotional impact. Audience reactions were then studied centrally and adjustments were made in upcoming shows using what had been learned. What began as education ended as show business. Its legacy is all over modern schooling in its spurious concept of Motivation.

Tent-Chautauqua did a great deal to homogenize the United States as a nation. It brought to the attention of America an impressive number of new ideas and concepts, always from a management perspective. What seemed even-handed was seldom that. The classic problem of ethical teaching is how to avoid influencing an audience to think a certain way by the use of psychological trickery. In this, Chautauqua failed. But even a partial list of developments credited to Chautauqua is impressive evidence of the influence of this early mass communication device, a harbinger of days ahead. We have Chautauqua to thank in some important part for the graduated income tax, for slum clearance as a business opportunity, juvenile courts, the school lunch program, free textbooks, a "balanced" diet, physical fitness, the Camp Fire Girls, the Boy Scout movement, pure food laws, and much, much more.

One of the most popular Chautauqua speeches was titled "Responsibilities of the American Citizen." The greatest responsibility was to listen to national leaders and get out of the way of progress. Ideas presented during Chautauqua Week were argued and discussed after the tents were gone. The most effective kind of indoctrination, according to letters which passed among Chautauqua’s directors, is always "self-inflicted." In the history of American orthodoxies, Chautauqua might seem a quaint sort of villain, but that’s because technology soon offered a way through radio to "Chautauqua" on a grander scale, to Chautauqua simultaneously from coast to coast. Radio inherited tent-Chautauqua, presenting us with model heroes and families to emulate, teaching us all to laugh and cry the same way. The great dream of utopians, that we all behave alike like bees in a hive or ants in a hill, was brought close by Chautauqua, closer by radio, even closer by television, and to the threshold of universal reality by the World Wide Web.

The chapter in nineteenth-century history, which made Chautauqua the harbinger of the new United States, is not well enough appreciated. Ideas like evolution, German military tactics, Froebel’s kindergartens, Hegelian philosophy, cradle-to-grave schooling, and systems of complete medical policing were all grist for Chautauqua’s mill — nothing was too esoteric to be popularized for a mass audience by the circuit of tent-Chautauqua. But above all, Chautauqua loved Science. Science was the commodity it retailed most energetically. A new religion for a new day.

The Chautauqua operation had been attractively planned and packaged by a former president of Masonic College (Georgia), William Rainey Harper, a man whose acquaintance you made on the previous page. Dr. Harper left Chautauqua eventually to become Rockefeller’s personal choice to head up a new German-style research university Rockefeller brought into being in 1890, the University of Chicago. He would eventually become an important early patron of John Dewey and other leading lights of pedagogy. But his first publicly acclaimed triumph was Chautauqua. Little is known of his work at Masonic College; apparently it was impressive enough to bring him to the attention of the most important Freemasons in America.

The Well-Trained Mind:...

Best Price: $2.63

Buy New $12.00

(as of 02:30 UTC - Details)

The Well-Trained Mind:...

Best Price: $2.63

Buy New $12.00

(as of 02:30 UTC - Details)

The real Chautauqua was not the peripatetic tent version but a beautiful Disney-like world: a village on a lake in upstate New York. William James went for a day to lecture at Chautauqua and "stayed for a week to marvel and learn" — his exact words of self-introduction to those teachers he spoke to long ago at Harvard. What he saw at Chautauqua was the ultimate realization of all reasonable thought solidified into one perfect working community. Utopia for real. Here it is as James remembered it for students and teachers:

A few summers ago I spent a happy week at the famous Assembly Grounds on the borders of Chautauqua Lake. The moment one treads that sacred enclosure, one feels one’s self in an atmosphere of success. Sobriety and industry, intelligence and goodness, orderliness and reality, prosperity and cheerfulness pervade the air. It is a serious and studious picnic on a gigantic scale.

Here you have a town of many thousands of inhabitants, beautifully laid out in the forest and drained, and equipped with means for satisfying all the necessary lower and most of the superfluous higher wants of man. You have a first class college in full blast. You have magnificent music — a chorus of 700 voices, with possibly the most perfect open-air auditorium in the world.

You have every sort of athletic exercise from sailing, rowing, swimming, bicycling, to the ball field and the more artificial doings the gymnasium affords. You have kindergarten and model secondary schools. You have general religious services and special club-houses for the several sects. You have perpetually running soda-water fountains and daily popular lectures by distinguished men. You have the best of company and yet no effort.

You have no diseases, no poverty, no drunkenness, no crime, no police. You have culture, you have kindness, you have equality, you have the best fruits of what mankind has fought and bled and striven for under the name of civilization for centuries. You have, in short, a foretaste of what human society might be were it all in the light with no suffering and dark corners.

Flickering around the edges of James’ description is a dawning consciousness that something is amiss — like those suspicions of some innocent character on an old Twilight Zone show: it’s so peaceful, so pretty and clean…it…it looks like Harmony, but I just have this terrible feeling that…something is wrong…!

When James left Chautauqua he realized he had seen spread before him the realization on a sample scale of all the ideals for which a scientific civilization strives: intelligence, humanity, and order. Then why his violently hostile reaction? "What a relief," he said, "to be out of there." There was no sweat, he continued disdainfully, "in this unspeakable Chautauqua." "No sight of the everlasting battle of the powers of light with those of darkness." No heroism. No struggle. No strength. No "strenuousness."

James cried aloud for the sight of the human struggle, and in a fit of pessimism, he said to the schoolteachers:

An irremediable flatness is coming over the world. Bourgeoisie and mediocrity, church sociables and teachers’ conventions are taking the place of the old heights and depths…. The whole world, delightful and sinful as it may still appear for a moment to one just escaped from the Chautauquan enclosure, is nevertheless obeying more and more just those ideals sure to make of it in the end a mere Chautauqua Assembly on an enormous scale.

A mere Chautauqua assembly? Is that all this monument to intelligence and order adds up to? Realizing the full horror of this country’s first theme park, James would seem to have experienced an epiphany:

The scales seemed to fall from my eyes; and a wave of sympathy greater than anything I had ever before felt with the common life of common men began to fill my soul. It began to seem as if virtue with horny hands and dirty skin were the only virtue genuine and vital enough to take account of. Every other virtue poses; none is absolutely unconscious and simple, unexpectant of decoration or recognition like this. These are our soldiers, thought I, these our sustainers, these are the very parents of our lives.

Near the end of his life, James finally understood what the trap was, an overvaluation placed on order, rational intelligence, humanism, and material stuff of all sorts. The search for a material paradise is a flight away from humanity into the sterile nonlife of mechanisms where everything is perfect until it becomes junk.

Education: Free & Comp...

Best Price: $4.00

Buy New $19.95

(as of 07:55 UTC - Details)

Education: Free & Comp...

Best Price: $4.00

Buy New $19.95

(as of 07:55 UTC - Details)

At the end of 1997, Chautauqua was back in the news. A young man living there had deliberately infected at least nine girls in the small town adjoining — and perhaps as many as twenty-eight — with AIDS. He picked out most of his victims from the local high school, looking for, as he put it, "young ladies…in a risk-taking mode." A monster like this AIDS predator could turn up anywhere, naturally, but I was struck by the irony that he had found the very protected lakeside hamlet with its quaint nineteenth-century buildings and antique shops, this idyllic spot where so many of the true beliefs of rationality made their American debut, as the place to encounter women unprepared to know the ways of the human heart. "In a risk-taking mode" as he puts it in instructively sociological jargon.

Have over a hundred years of the best rational thinking and innovation the Western world can muster made no other impact on the Chautauqua area than to set up its children to be preyed upon? A columnist for a New York paper, writing about the tragedy, argued that condom distribution might have helped, apparently unaware that the legitimization of birth control devices in the United States was just one of many achievements claimed by Chautauqua.

Other remarks the reporter made were more to the point of why we need to be skeptical whether any kind of schooling — and Chautauqua’s was the best human ingenuity could offer — is sufficient to make good people or good places:

The area has the troubles and social problems of everywhere. Its kids are lonely in a crowd, misunderstood, beyond understanding and seeking love, as the song says, in all the wrong places…. Once, intact families, tightly knit neighborhoods and stay-at-home mothers enforced community norms. Now the world is the mall, mothers work, and community exists in daytime television and online chat rooms.

- Forced medical inspection had been a prominent social theme in northern Germany since at least 1750.

- For instance, how else to get a handle on the Columbia Teachers College bureau head who delivered himself of this sentence in Education Week (March 18, 1998), in an essay titled "Altering Destinies": "Program officials consider no part of a student’s life off limits."

- A P. S. 87 parent, Sol Stern, brought this information to my attention, adding this assessment, "The idea that schools can starve children of factual knowledge and basic skills, yet somehow teach critical thinking, defies common sense." Mr. Stern in his capacity as education editor of New York’s City Journal often writes eloquently of the metropolitan school scene.

- This essay is packed with references to Unitarians, Quakers, Anglicans, and other sects because without understanding something about their nature, and ambitions, it is utterly impossible to comprehend where school came from and why it took the shape it did. Nevertheless, it should be kept in mind that I am always referring to movements within these religions as they existed before the lifetime of any reader. Ideas set in motion long ago are still in motion because they took institutional form, but I have little knowledge of the modern versions of these sects, which for all I know are boiling a different kettle of fish.

Three groups descending from the seventeenth-century Puritan Reformation in England have been principal influences on American schooling, providing shape, infrastructure, ligatures, and intentions, although only one is popularly regarded as Puritan — the New England Congregationalists. The Congregational mind in situ, first around the Massachusetts coast, then by stages in the astonishing Connecticut Valley displacement (when Yale became its critical resonator), has been exhaustively studied. But Quakers, representing the left wing of Puritan thought, and Unitarians — that curious mirror obverse of Calvinism — are much easier to understand when seen as children of Calvinist energy, too. These three, together with the episcopacy in New York and Philadelphia, gathered in Columbia University and Penn, the Morgan Bank and elsewhere, have dominated the development of government schooling. Baptist Brown and Baptist Chicago are important to understand, too, and important bases of Dissenter variation like Presbyterian Princeton cannot be ignored, nor Baptist/Methodist centers at Dartmouth and Cornell, or centers of Freethought like Johns Hopkins in Baltimore and New York University in New York City. But someone in a hurry to understand where schooling came from and why it took the shape it did would not go far wrong by concentrating attention on the machinations of Boston, Philadelphia, Hartford, and New York City in school affairs from 1800 to 1850, or by simply examining the theologies of Congregationalism, Unitarianism, Hicksite and Gurneyite Quakerism, and ultimately the Anglican Communion, to discover how these, in complex interaction, have given us the forced schooling which so well suits their theologies.

- It was not really until the period around 1914 that sufficient teacher training facilities, regulated texts, controlled certification, uniform testing, stratified administrative cadres, and a sufficiently alienated public allowed the new age of schooling to tentatively begin.

- In conservative political theory dating back to Thucydides, meritocracy is seen as a box of trouble. It creates such a competitive flux that no society can remain orderly and loyal to its governors because the governors can’t guarantee preferment in licensing, appointments, grants, etc., in return. Meritocratic successes, having earned their place, are notoriously disrespectful. The most infamous meritocrat of history was Alcibiades, who ruined Athens, a cautionary name known to every elite college class, debating society, lyceum, or official pulpit in America.

- I remember the disbelief I felt the day I discovered that as a committee of one I could easily buy paper, milk, and any number of other school staples cheaper than my school district did.

Chapters of The Underground History of American Public Education:

- Prologue

- Chapter 1: The Way It Used To Be

- Chapter 2: An Angry Look At Modern Schooling

- Chapter 3: Eyeless In Gaza

- Chapter 4: I Quit, I Think

- Chapter 5: True Believers and the UnspeakableChautauqua

- Chapter 6: The Lure of Utopia

- Chapter 7: The Prussian Connection

- Chapter 8: A Coal-Fired Dream World

- Chapter 9: The Cult of Scientific Management

- Chapter 10: My Green River

- Chapter 11: The Crunch

- Chapter 12: Daughters of the Barons of Runnemede

- Chapter 13: The Empty Child

- Chapter 14: Absolute Absolution

- Chapter 15: The Psychopathology of EverydaySchooling

- Chapter 16: A Conspiracy Against Ourselves

- Chapter 17: The Politics of Schooling

- Chapter 18: Breaking Out of the Trap

- Epilogue

John Taylor Gatto is available for speaking engagements and consulting. Write him at P.O. Box 562, Oxford, NY 13830 or call him at 607-843-8418 or 212-874-3631.