Some advice: Don’t get shot in the face. I don’t care what your friends tell you, it isn’t a good idea. Further, avoid corneal transplants if you can. If you find a coupon for one, in a box of Cracker Jacks maybe, toss it. Transplants are miserable things. Unless you really need one. What am I talking about? Eyes, and losing them, and getting them back. On this, I am an accidental authority.

Long long ago, in a far galaxy, the United States was bringing democracy to Viet Nam, which had barely heard of it and didn’t want it anyway. As an expression of their desire to be left alone, the locals spent several years shooting Americans. I was one of them: a young dumb Marine with little idea either where I was or why. But that was common in those days.

A large-caliber round, probably from a Russian 12.7mm heavy machine gun, came through the windshield of the truck I was driving. The bullet missed me, barely, because I had turned my head to look at a water buffalo in the paddy beside the road. Unfortunately the glass in front of the round had to go somewhere, in this case into my face. Not good. I didn’t like it, anyway.

So I got choppered to the Naval Support Activity hospital in Danang with the insides of my eyes filled with blood, which I didn’t know because my eyelids were convulsively latched shut. An eye surgeon there did emergency iridectomies — removing a slice of the iris — so that my eyes wouldn’t explode. He also determined that powdered glass had gone through my corneas, through the anterior chamber, through the lens, and parked itself in the vitreous, which is the marmalade that fills the back of the eye. It had not reached the retina, though they couldn’t tell at the time, which meant that I wasn’t necessarily going to be blind. Yet.

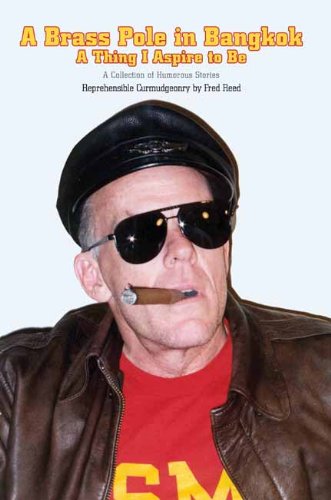

A Brass Pole in Bangkok

Buy New $2.99

(as of 08:55 UTC - Details)

A Brass Pole in Bangkok

Buy New $2.99

(as of 08:55 UTC - Details)

Two weeks followed of lying in a long ward of hideously wounded Marines. (I hope this part isn’t boring, but it explains what happened later.) My face was bandaged, but I remember well what the place sounded like. I heard stories. The two tank crewmen across the aisle from me, were burned over most of their bodies. An RPG had hit their tank, the cherry juice — hydraulic fluid, I mean — had cooked off, and cooked them too. The other two guys burned to death. It’s hard to get out of a tank filled with flame and smoke with your skin peeling off.

But that’s neither here nor there, being merely among the routine fascinations of military life in those days. Anyway, every two hours a Vietnamese nurse came by and injected me with what felt like several quarts of penicillin. Perhaps I exaggerate in retrospect: Maybe it was only one quart. The reason was that if your eyes are full of blood, and decide to become infected, you are categorically, really and truly, beyond doubt, blind. After so much penicillin, my breath alone would have stopped the Black Death.

What saved me, the doctors speculated, was that the tremendous energy of the 12.7 round had instantaneously heated the glass powder — it wasn’t much more than powder — and thus sterilized it. If a bullet is going to come through your windshield, make sure it has lots of energy.

Bear with me a bit more. I’m going to explain what happened so you will understand that eye surgeons are the best people on this or any other planet, and probably in league with spirits, because the things they do are clearly impossible.

After stops at the military hospital in Yokota, Japan, and a long flight in a C-141 Medevac bird in which the guy slung in the stretcher above me, full of tubes, died en route, I ended up in Bethesda Naval Hospital, Maryland, in the suburbs of Washington, DC. I spent a year there, and had the first eight of fourteen eye operations. (See what I mean about being in league with spirits? Any fool knows you can’t cut an eye open that many times, sucking things out, sewing things in, and expect it to see. Well, they did, and it did. Magic, I tell you.)

Now, eyes are special parts. Ask any soldier what he most doesn’t want, and he’ll tell you being paralyzed, blinded, and castrated, probably in that order. Losing a leg is a nuisance. In fact, it’s a royal, wretched, motingator of a nuisance, but that’s all it is. No, you won’t be a running back for the Steelers. But you can walk, sort of, chase girls, travel, be a biochemist. Not optimal, but you can adapt.

Eyes are different. On the eye ward, I watched the blind guys come in from the field. They curled up in bed and slept for days, barely ate, wouldn’t talk much. I didn’t so much do this because it wasn’t clear that I was going to be blind. Once the blood cleared the doctors could see that I had good retinas and, though I was going to have a fine case of traumatic cataracts, those were fixable. This was not true of Ron Reester, though, who had a rifle grenade explode on the end of his rifle. His eyes were definitively jellied, and that was that. Then there was a kid from Tennessee, maybe eighteen, with both eyes gone and half his face. I was there when his betrothed, still a senior in high school, came to see him. It was almost enough to make me think that wars weren’t such a hot idea.

It’s funny how people adapt to being blind. Reester, also from Tennessee — the South got hit hard in Vietnam — came out of his depression after a few weeks and became something of a character. Clowning takes your mind off things, which is what you need most.

After cataract surgery I had good vision for a while and they kept me on the ward to see whether something catastrophic might happen. Nothing did, really. I had minor hemorrhages and a fixable retinal detachment, but nothing else. Anyway, Reester decided he wanted to sight-see in Washington, though he was stone blind. Another guy on the ward was McGoo, or so we called a shot-up Navy gunner from the riverine forces in the Delta, the fast heavily-armed patrol boats, PBRs. McGoo also had thick glasses from cataract surgery, thus the name. Anyway, McGoo, Reester, and I would go downtown to see things.

I remember we pointed Reester at the Washington Monument once and told him what it was. “Oh, wow, that’s really magnificent, I didn’t know it was so tall,” he said, or something similar. Pedestrians thought we were being horribly cruel to a blind guy. No. He was having a hell of a time. And it was something to do. There wasn’t much to do on the ward.

Some of us adapted to blindness better than others. The Tennessee kid with half a face and no longer a girlfriend was somber and stayed to himself. I couldn’t blame the girl. She was still just a teenager and had figured to marry her good-looking sweetheart from high school, and now he was blind and looked like a raccoon run over by a truck. She would have spent a life caring for a depressive horror living on VA money. It was a lot to ask. I don’t know what happened to him. He just faded away somehow.

Reester made the best of things once he got beyond the first couple of weeks. He was a smooth-talking Elvis simulacrum and the concussion that jellied his eyes hadn’t made him ugly. At parties on Capitol Hill sponsored by congressmen who wanted to appear interested in Our Boys — nobody is more patriotic than a politician in election years — Reester made time with the girls supplied from local universities for the purpose.

We all lost touch with each other on leaving the ward, but a few years ago, I bumped into him via the Web. I called and we talked a bit. He had become a serious Christian and did things for vets.

To shorten the tale, I ended up with not just cataract surgery but also vitrectomies (removing the marmalade) in both eyes, leaving them full of water and nothing else. For a while both eyes actually worked, but the right one eventually gave up. At Bethesda the surgeons liked me and let me borrow some of their textbooks, so I ended up scrubbing and watching several operations in the OR. I liked that.

Eye surgery has its moments. Consider a vitrectomy. Various reasons account for this procedure, such as that the vitreous humor — the marmalade — is pulling on the retina, which can lead to detachments.

A vitrectomy is done by making three holes in the white part of the eye. In the first goes a tube, really more like a needle, that pumps saline in and out of the eye to keep it inflated. Otherwise as the vitreous was extracted, the eye would slowly collapse. Another hole accommodates a light pipe, made of optical fiber and attached to the operating microscope, so that the surgeon can see what he is doing inside the eye.

The third hole is for Ms. Pacman. OK, technically a microvit, which is a tube with a thing like, well, like Ms. Pacman, on the end. It chops up the vitreous — the “V” in technical talk — and sucks it out. Yes, I know. This is obviously impossible. Ophthalmic surgeons have no respect for possibility or the lack of it. They just do it anyway. Bless them.

The thing is, the patient can see all of this going on inside his eye. Really. It’s like watching shadow puppets. The microvit is clearly visible like a little rotorooter and you can see the snipping action of the cutter-part. Ms. Pacman, I tell you. I remember watching it go after a piece of black crud of some sort, snipsnipsnip, and eat it. It is a tribute to the efficacy of federal dope that the patient doesn’t leap up and run screaming from the room. You just don’t care. The whole business is dreamy, a sort of warm glowing Buddhist light show.

So, I had one good eye, which is plenty. There are only three important levels of vision — reading, walking, and none. I could read fine. Everything else, such as thick cataract glasses that made me look like a visiting Martian insect, is detail.

Physically, anyway.

On the eye ward, we seemed pretty sane. Spirits were good, or seemed to be. We were a bunch of tough young guys, badly shot up but seeming — seeming — to hold up well. We were all of the same Marine culture, given to the same sardonic black humor, and free, when wounds permitted, to roam downtown Washington. Had you come to the ward, you would have thought that all was well.

Because, you see, on the ward we weren’t freaks, with our coke-bottle glasses and scars and white canes. Or maybe we were all freaks, so it didn’t matter. One fellow, in addition to eye problems, had suffered a horrendously shattered jaw when an AK rounds hit it. The surgeons had to remove all of the bone, leaving him with an oddly flapping lower part of his mouth. He lived on mush pumped into his stomach through a nasogastric tube always dangling from his nostrils. We called him Jawless and kidded him about it. On the ward, it didn’t bother him. We were all freaks. So what?

The bitterness came later. You have heard of PTSD? We hadn’t. “Post-traumatic stress disorder” would have sounded to us either imaginary — hey, there was nothing wrong with us — or else the reaction of fragile wusses. We were fine in the head.

Except we weren’t. Not even close.

I joke about my glasses, tremendously thick things. I had to wear them: Because of corneal damage, my eyes wouldn’t tolerate contacts. For a young reasonably good-looking man they aren’t funny. They do indeed make you a freak. Girls do an unconscious double-take and aren’t interested. Guys in pool halls think you must be a wimp, in which case you had better not be. You just look funny, or think you do, which is almost as bad. If you don’t believe a pair of glasses can change your life, take a beautiful young woman and put her in cataract lenses. Instant introversion. Her self-confidence will vanish and she will hate the damned things like poison. How the other sex reacts to us matters.

Further, while I could see reasonably well, I knew that I could go blind at any moment. With really screwed up eyes, there is always a danger of (another) retinal detachment, of hemorrhage, of cystoid macular edema, of loss of central vision. I figured I was living on borrowed time.

And so, when the Corps retired me on disability, I became an anti-social drifter, thumbing across the continent, often alone, subconsciously angry at having been used and thrown away in a pointless war. You don’t want to look inside the heads of men who have been badly wounded. Dark things live there. The expectation of going blind intensifies the fury and bitterness. Few talk about this. I seldom have. But it’s there.

Social dysfunction and aimless wandering expose you to many interesting things which when written about (I discovered) can be sold to magazines. Writing was a good racket for the loner I had become. I was irritable, jumpy, easily pissed off, distant, hostile to authority, believed in nothing, was going nowhere. (See? You really should avoid getting shot in the face.) But by writing about the various stupid things I did, I could package dysfunction as the artistic temperament, and sell myself not as a disagreeable oddball but a wild free spirit eschewing the trammels of conventional life. It was fraud, but saleable fraud.

All went reasonably well till two years ago when the cornea of my good eye started going south. Things got blurry, and then blurrier. I saw an unwholesome trend.

OK, physiology. What makes a cornea stay transparent is that the inner layer of cells, the endothelium, suck water out of it. This keeps it from getting bloated and edematous and foggy. My cornea had undergone a hard existence, being opened up every so often by surgeons, apart from being shot early in its life. You can only ask so much of a cornea. It’s a law of ophthalmology.

So I flew back from Mexico, where I live, and groped my way out to Bethesda Naval again, where an ace eye guy, Dr. Phil Stanley, determined that I needed a new windshield. The experts, he said, were at the Wilmer Eye Institute of Johns Hopkins, in Baltimore. He wrote me a Tricare referral, which is technical military talk meaning that the Navy would pay for it. This mattered. Transplants ain’t cheap, tending to go for eight grand and substantially up.

Now, let me tell you some stuff about corneal transplants, partly to buttress my theory about ophthalmologists being in league with spirits, and partly because it’s interesting.

The cornea of course is the front transparent part of the eye, what you would hit first if you stuck a stick in your eye. (Don’t do it. Take my word.) The surgeon gets a used cornea from somebody who died and had the decency to be an organ donor.

Then he can do either of two kinds of transplant. In the first kind (PK, or penetrating keratoplasty, if you want to impress people at parties) involves cutting out your whole cornea, all five layers of it, and replacing it. This by today’s standards is a clunky, heavy-handed approach and involves risks of rejection, mechanical weakness, and other not-so-good things. The other kind of transplant is called a DSEK (Descemet’s stripping endothelial keratoplasty). In this the back layers of the donor cornea are peeled off, rolled up like a magazine you’d swat a dog with, and inserted in a tiny hole in the cornea. The roll unrolls, sticks to the back of the cornea, and all is well. A bubble of air pumped in between the lens and the back of the cornea holds the transplant in place until it decides to stick. This, alas, was impossible in my case because, the lens and vitreous both having been removed, my eye was full of water. The bubble would have floated off into the back of the eye.

So I had to have a PK.

OK, so I show up in Washington a few weeks before surgery with Violeta, my splendid Mexican wife, who has been in and out of the US enough that the TSA Nazis are almost civil with her. I needed her to keep me from bumping into things, since by this time my tired old cornea had roughly the transparency of a manhole cover.

There’s nothing like losing your vision to convince you that you want it back.

The night before I was to be sacrificed we stayed with friends near Baltimore who would drive me to Johns Hopkins. They would then go to tourist things while I was vivisected. I thought they had the better part of the deal.

My surgeon was Dr. Albert Jun, a Chinese guy out of Harvard. (A good friend’s Philippina wife had really nasty breast cancer seven years ago. Her surgeon was a Vietnamese gal out of Harvard. I can almost see patterns developing here.) Anyway, Dr. Jun was one very impressive guy, which is what I wanted under the circumstance. He had explained that I had to have the old, clunky kind of transplant. In other words they were going to put a large hole in my eye. This gives you lots to think about the night before.

Dr. Jun asked me whether I wanted him to do some other repairs while he was at it — for example, repair my iris, which had been chopped up and didn’t control light as well as it ought. Further, he could have sewn an artificial lens in and then done a DSEK, which, as mentioned before, has advantages. With the new lens, I wouldn’t have needed my current cataract glasses. Thing is, sewing in a lens would have added at least fifteen minutes to the surgery and increased the operative risk, which I wanted no part of. He didn’t recommend it either, given that I had only one eye to play with. Nope. I’ve looked like a mutant arthropod for forty years. I know longer aspire to a career in movies. And one thing about cataract lenses is that they are thick, probably enough to stop an anti-tank round. I didn’t need anything poking me in the eye. So we went with what gave the highest likelihood of a working orb.

Now, here’s the really neat part. Eye surgery is usually done under a local anesthetic. They pump you full of Valium or Demerol or some other kind of Buddha juice. In other words, you stay conscious and awake. This is done because general anesthesia carries certain risks, such as death, and if you wake up and start vomiting enthusiastically, which can happen, you can blow the new cornea out of the eye. (Or close enough that you really don’t want to do it.) I was opposed to both of these eventualities. Still being awake while your eye is being cut open is not as fun as a Grateful Dead concert. It does, however, involve as many drugs.

After surgery, the hospital folk put me in a recovery room until they determined that I was pretty much normally awake and could drink apple juice. Actually I wanted a double bourbon, but I sensed that it was not an appropriate request. I dressed myself successfully and left with Vi and friends.

My vision was awful beyond imagining. Everything was a textured gray like bad wallpaper, with foul-looking things floating around in it. Think dirty dishwater. It was clear to me that I would never see again. People were just vague shadows. My tall friend walked in front to I wouldn’t bump into low-hanging objects with my eye, and Vi followed behind to guide me. Splendid. Just splendid.

And then the eye started to hurt. A defect of anesthesia is that it doesn’t last. It wasn’t agony, but enough to keep you miserable and gobbling Tylenol. Not aspirin or ibuprofen, though, which are anticoagulants and encourage bleeding. After eye surgery, a massive hemorrhage is recommended by almost no one.

I thought about writing a book, Fred in the Land of Shadows. All sorts of bric-a-brac floated around in my visual field. Most of it, maybe all, was sorta-clotted blood, which looks black. These things come in the form of what look like irregular flakes, and string-balls. These latter resemble tangles of black kite-string. They drift and float and when they change position relative to the retina, they grow longer or shorter. I felt like an amateur kaleidoscope.

Eye drops, eye drops, and more eye drops. Antibiotics. A traumatized cornea, having been removed from its accustomed owner, transported in some weird solution, and sewn into a total stranger, does not need an infection. Steroids, every two hours. Now, you might think that steroids would make an eye bulk up like a softball and pop out of your skull, but these are anti-inflammatory, not anabolic.

The worst thing about recovery is that it is invisibly slow. Corneas don’t root themselves into place quickly, so the stitches stay in for a year. I had fourteen of them, and felt like a sewing sampler. The bad part is that it takes six to eighteen months for the cornea to clear. This means that you wake up every morning, and nothing has changed. You become convinced that nothing will ever change. Six weeks after the surgery, I was sure that nothing had improved.

Being unable to read stretches the word “unpleasant” to its limits. What do you do all day? Eventually you can write a little in seventy-two point type, but books don’t come in seventy-two point type. I can listen to only so much music. I took to sitting in Tom’s Bar, ingesting beer and chili, and listening to football. We’re not talking the onset of alcoholism to combat a possibly terminal despair, but just an agreeable place that didn’t require seeing much of anything. I could recognize friends only by voice. It was ridiculous.

People sometimes asked me whether I was depressed. No. I might have committed suicide from boredom, but not depression. I was certainly annoyed as hell. At what, I wasn’t sure, but I was quite sure that being mostly blind wasn’t how it spoza be.

On the Busted Leg Principle, I didn’t feel sorry for myself. The leg principle is that a broken leg is a nuisance, but a missing leg is a problem. The doctors said I was doing fine and, being in league with spirits, they had sources of information hidden from me. Anyway, people who feel sorry for themselves are mortally boring, even to themselves. I’d rather eat chili.

But I was getting excruciatingly tired of the whole business.

Curmdugeing Through Pa...

Buy New $2.99

(as of 08:05 UTC - Details)

Curmdugeing Through Pa...

Buy New $2.99

(as of 08:05 UTC - Details)

Every morning I’d look out the window of the bedroom at the house of a distant neighbor who had a sort of picket fence, which I could see only as a white blur. One morning I noticed that he had replaced the pickets with ones that were more visible, because I could see them, kind of. But definitely. Further, the words “A Time to Speak,” on the spine of the book by Robert Bork which I had optimistically bought before surgery, had clarified themselves. I could read them from a foot away. Maybe I wasn’t ready for sniper’s school, but the trend was in the right direction.

At this point I’m just waiting. I don’t feel traumatized, just impatient. Friends sometimes asked me, “Wasn’t it terrifying to go into surgery like that with just one eye and you might lose it?” It depends on who you are, I guess. I’m easily enough terrified of a lot of things — angry hornets weighing three pounds, incoming artillery, brainless and vaguely angry bureaucrats, thugs with knives. After enough practice with eye surgery, you just sort of flow with the odds. At least, I do. Statistically, it’s very likely to work. So assume it will, and if it doesn’t, deal with it then. Sure, even long after surgery the new cornea can be rejected by the immune system, which can be more effective than it is aware of what you really want it to do. That’s grim when you think about it, so I don’t.

When I finally reach 20/30, I’m going to spend two weeks trekking in Nepal and then go diving in the Caribbean. You only live once (unless you believe the Hindus, but that’s too horrifying to contemplate) so I say grasp at any pretext.

Reprinted with permission from The Unz Review.