AUTHOR’S NOTE:

On July 13, the Cato Institute published on its website libertarianism.org an article entitled “The Errors of Nostalgi-tarianism” by Steve Horwitz, a libertarian economics professor at Ball State University in Muncie, Indiana.

Horwitz’s article was a critique of a fundraising letter that I recently sent to supporters of The Future of Freedom Foundation requesting help with upgrading our website and with an outreach campaign that we are launching to find new libertarians.

On July 23, I sent a response to Horwitz’s article to an editor at Cato, requesting that they share it with the readers of libertarianism.org.

One of Cato’s associate editors informed me that they would not post my response because, he said, it did not “meet libertarianism.org’s editorial standards.” He informed me that they would be open to reconsidering their decision if I met three conditions: (1) I revise my response to their satisfaction; (2) I delete the section of my response that explains FFF’s methodology for advancing liberty; and (3) I shorten my response so that its number of words would approximately equal the number of words in the Horwitz critique.

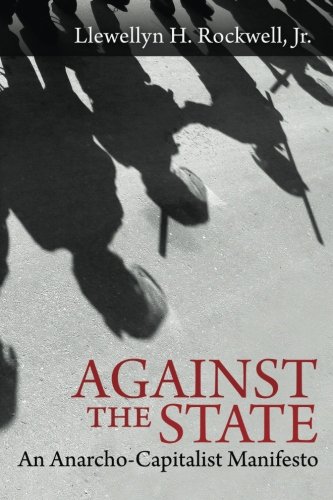

Against the State: An ...

Best Price: $5.02

Buy New $5.52

(as of 11:35 UTC - Details)

Against the State: An ...

Best Price: $5.02

Buy New $5.52

(as of 11:35 UTC - Details)

I advised him that those conditions were unsatisfactory to me. Consequently, Cato chose not to share my response to the Horwitz article with the readers of libertarianism.org.

My response to Horwitz’s critique of my FFF fundraising letter appears below.

Jacob Hornberger

President

The Future of Freedom Foundation

*****

In an article entitled The Errors of Nostalgi-tarianism,” which was recently published by the Cato Institute’s website libertarianism.org, Ball State University economics professor Steve Horwitz, criticized a fundraising letter that I recently sent out to supporters of The Future of Freedom Foundation seeking help with upgrading our website and with an outreach campaign to find new libertarians.

In his critique of my fundraising letter (which followed a similar critique on Horwitz’s Facebook page), Horwitz takes me to task for expressing nostalgia for the way things were in late 19th-century America. If I had actually said what he accused me of saying, I would agree with the points he makes. Unfortunately for Horwitz, however, the words I used did not say what he said they said.

Most of us are familiar with the term “straw man.” But just in case someone isn’t familiar with the term, the following is a common definition: “an intentionally misrepresented proposition that is set up because it is easier to defeat than an opponent’s real argument.”

The position that Horwitz wanted to attack was one that would have stated as follows: “I long for late 19th-century America because it was such a free society.”

That’s not what I said in my fundraising letter. Here is what I said (with italics added for emphasis):

My favorite period in U.S. history is the latter part of the 1800s. It wasn’t a pure, 100-percent libertarian society by any means, but it is the closest that mankind has ever come. Imagine: No income tax, IRS, drug laws, DEA, Social Security, Medicare, or Medicaid; no farm subsidies, licensure, welfare, public schooling, gun control, immigration controls, Federal Reserve, paper money, minimum wage, or price controls; no military-industrial complex, CIA, NSA, TSA, FBI, Homeland Security, foreign aid, foreign wars, or foreign interventions.

Americans proved that it can be done. That is our baseline here at FFF. We want to restore those principles and build on them. We want America to lead the world to even greater heights of freedom and prosperity.

In both his Facebook critique and in his article on libertarianism.org, Horwitz omitted the second paragraph. Why did he do that? Because it didn’t fit with the narrative that he wanted to criticize. It was inconsistent with the straw man who he wished to target — i.e., the libertarian who expresses nostalgia for American life in the late 1800s without pointing out that there were violations of liberty during that era that libertarians do not endorse or condone.

Those two paragraphs in my fundraising letter point out two things:

First, my acknowledgment that 19th-century America was not a pure, 100-percent libertarian society. What does that mean? That means that I am stating that in 19th-century America, there were infringements on liberty that I am not endorsing.

Could I have detailed what such infringements were? Of course. I could have pointed to the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, the crony capitalism, the corrupt land grants to the railroads, tariffs, the denial of voting rights for women, and even one that Horwitz points out — the Comstock Law of 1873.

But let’s keep in mind an important thing: This was a two-page fundraising letter being sent to our supporters at FFF, not a 2,500-word article on libertarianism.org.

Second, by specifically enumerating libertarian policies in the late 19th century, I am conveying to the reader the aspects of that era that I consider positive. In fact, that’s where the second paragraph — the paragraph that Horwitz omitted in both his Facebook post and his libertarianism.org article — comes into play: I specifically say: “Americans proved that it can be done. That is our baseline here at FFF. We want to restore those principles and build on them. We want America to lead the world to even greater heights of freedom and prosperity.”

Does that sound like a libertarian who is expressing unconditional and unqualified nostalgia for late 19th-century America? Does it sound like a libertarian who is defending or even ignoring the infringements on liberty that existed during that time? Or does it sound like a libertarian who is acknowledging that there were, indeed, infringements on liberty and that we should take the positive freedom principles of that era, make them a baseline goal for today, and build on that baseline with the aim of leading the world to the freest society in history?

But let’s go to a more important point: Horwitz’s claim that today’s America is freer than 19th-century America. He couldn’t be more wrong, even factoring in the infringements on liberty during that time. Even given such infringements, it is impossible for any libertarian to reasonably and rationally argue that today’s Americans live in a freer society than Americans did in the late 19th-century.

Of course, when it comes to analyzing two different societies, we necessarily have to compare imperfect institutions. Given that human beings are imperfect, it would be impossible to expect any people to ever have a perfectly libertarian society. So, we are necessarily comparing imperfect systems — the imperfect society of late 19th-century America and the imperfect society of 21st-century America.

Moreover, it is certainly possible to have certain groups who are denied liberty in some particular way in Society 1 while those same groups enjoy the removal of such infringements in Society 2. Depending on the nature and extent of the infringement, it is entirely possible that such groups would choose to live in Society 2 even if Society 1 is in all other respects a pure libertarian society.

The Politics of Obedie...

Buy New $2.99

(as of 04:00 UTC - Details)

The Politics of Obedie...

Buy New $2.99

(as of 04:00 UTC - Details)

For example, suppose Society 1 is based on pure libertarian principles with one exception: slavery for blacks. Everyone, except blacks, is free to engage in economic enterprise without state interference, to accumulate unlimited amounts of wealth, and decide for himself what to do with it. Everyone, except blacks, is guaranteed civil liberties. Society 2 is based on socialist principles, where the state owns and operates everything and where everyone works for the state.

I think we can say with 100 percent certainty that blacks would choose to live in Society 2, notwithstanding the serfdom, poverty, and tyranny that comes with living in a socialist society. That’s because direct slavery is such an egregious infringement on liberty.

But suppose Society 1 is based on pure libertarian principles, with only one exception: Blacks are prohibited from sending information on contraceptives through the mail (i.e., the Comstock Law of 1873). Everyone, including blacks, has the right to engage in economic enterprise without state interference, accumulate unlimited amounts of wealth, and decide for himself what to do with his own money. Freedom of speech, freedom of the press, due process of law, and the right to vote apply to everyone, including blacks.

Society 2 is a socialist society, one in which the state owns and operates everything and where people are jailed for criticizing the government. In Society 2, however, blacks and everyone else are free to send information on contraceptives through the mail.

Now what happens? My hunch is that most Americans, including blacks, would choose Society 1, notwithstanding the clear infringement on liberty and the clear violation of the rule of law that comes with the Comstock Law.

Which society would you choose? I would, without a doubt, choose Society 1 and work toward getting rid of the offending law. That is, I would make the positive principles of Society 1 my baseline and work toward expanding that baseline, which is precisely the point I was making in my 2-page fundraising letter to FFF’s supporters.

Let’s consider women, one of the groups that Horwitz used as an example to show how oppressive life was in late 19th-century America. Horwitz points to the fact that women were denied the right to vote and had their control over their property restricted as soon as they got married.

Fair enough. Those infringements did, in fact, exist. They were wrong. They were violations of libertarian principles.

Yet, consider this: millions of women were flooding into America throughout the 1800s and especially in the latter part of the century. In fact, when Ellis Island opened on January 1, 1892, the very first immigrant who was processed was an Irish girl named Annie Moore. According to a 2015 article entitled “New Beginnings: Immigrant Women and the American Experience” on the website of National Women’s History Museum,

Though Annie herself is remembered for being the first, her experiences in America were very much like those of millions of other women who chose to make a new home in a new country. Like those before and after, the women and girls who came through Ellis Island transformed America socially, politically, and economically. Women historically have accounted for almost fifty percent of immigrants and currently exceed that. Women’s motivations for migration have been varied and complex. Gender has influenced migrant women’s choices to immigrate as well as their opportunities and challenges upon arrival. Women immigrants have played a dynamic role in transforming America socially, politically, and economically.

What gives? Were all those immigrant women unaware that women in America were denied the right to vote? Did they not know that their control over their property was restricted if they got married? Did they not know that the Comstock Law of 1873 made it illegal for them to send information on contraceptives through the mail?

The fact is that none of these infringements on liberty mattered enough to them to keep them from coming to the United States, especially when compared to the imperfect societies they were fleeing. They were coming to a society in which there was no … well, permit me to again quote my fundraising letter:

No income tax, IRS, drug laws, DEA, Social Security, Medicare, or Medicaid; no farm subsidies, licensure, welfare, public schooling, gun control, immigration controls, Federal Reserve, paper money, minimum wage, or price controls; no military-industrial complex, CIA, NSA, TSA, FBI, Homeland Security, foreign aid, foreign wars, or foreign interventions.

Those libertarian principles were not limited to “propertied white men.” They applied to everyone, including women, blacks, Jews, and people of Italian, German, Hispanic, and Irish descent.

First, everyone was free to engage in economic enterprise without state interference and to accumulate unlimited amounts of wealth. No state-imposed mandatory charity, including Social Security and Medicare, for anyone.

Second, everyone, not just “propertied white men,” enjoyed the economic and financial benefits that came with a gold-coin standard, as compared to the state plunder and looting that comes with fiat (i.e. paper) money and a Federal Reserve System.

Third, no one was subject to a state system of torture, assassination, mass surveillance, and indefinite detention, as Americans and others are today.

Fourth, contrary to what Horwitz asserts, no one was conscripted from the Civil War to World War I. While U.S. officials declared that men were subject to military duty in the Spanish-American War in 1898, no one was conscripted.

Women immigrants were fleeing Europe and Asia because they were rejecting statist societies in favor of the free-market, limited-government system in late 19th-century America, notwithstanding the fact that American women were being denied the right to vote, had their rights over property restricted upon marriage, and the Comstock Law of 1873 that made it illegal to send information about contraceptives through the mail.

Like their male counterparts, those immigrant women were voting with their feet. They were choosing America. And they just kept coming. Why? One reason is because they knew that they were living in the freest society in history, notwithstanding the exceptions. Another reason is that both women and men were doing fantastic economically. America’s vibrant free-market system enabled them to sustain their lives and the lives of their children through labor and, even better, enabled them to prosper, even get rich, which many of them did.