In the popular TV series, Gotham (it’s a prequel to the Batman story) there’s an episode called “Everyone Has His Cobblepot” — a reference to something embarrassing in one’s past.

The Chevy Vega is GM’s Cobblepot.

Like most failures, it wasn’t intentional. But it was — in retrospect predictable. Chiefly because then-GM President Ed Cole rushed the car’s development. In particular, development of what would become its centerpiece — and its Achilles Heel: a new-design aluminum engine that would not use steel cylinder liners. Instead, using a new casting process and metallurgy developed jointly with Reynolds Metals (of Reynolds Wrap fame), the 2.3 liter engine block was machined to accept the pistons without the need for pressed-in steel liners. This saved weight and simplified the manufacturing process.

It wasn’t a bad idea at all.

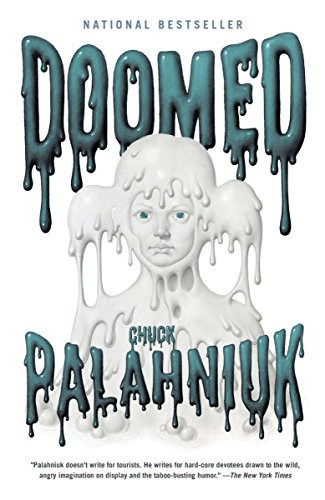

Doomed

Best Price: $3.36

Buy New $10.37

(as of 08:45 UTC - Details)

Doomed

Best Price: $3.36

Buy New $10.37

(as of 08:45 UTC - Details)

But the execution was a clown car comedy of engineering errors.

To save a few bucks per car — the source waters of so many problems — Chevy engineers decided to bolt a cast iron head to the aluminum block. The two dissimilar metals have very different expansion and contraction rates when heated. By itself, this wasn’t fatal. Many engines have alloy blocks and cast iron heads. But they did not have some of the Vega engine’s other design features.

For openers, the engine was top heavy. In-house, it was referred to as “the world’s tallest, smallest engine” by already-worried engineers. The engine was prone to vibrating like a Martini mixer and would also overheat — the former issue due to the tall-boy layout and a lack of sufficient counterbalancing, the latter to a marginal cooling system and a tendency to burn oil excessively.

To Band Aid (rather than fix) the engine problem, engineers fitted the car with loose rubber engine mounts, so the owner wouldn’t notice the vibration as much. But it continued to shake — and as the coolant ran low (which was not hard to do given a mere six quart capacity system and a two-row radiator) the little engine would begin to run ever-hotter. Which it was already susceptible to doing because of its siamesed bores (no coolant flowing in between the cylinders).

It was like a delayed-action fuse.

What happened was the engine would shake, shake, shake (cue KC & The Sunshine Band) as coolant drip, drip, dripped. The temp needle would begin its inevitable ascent toward the red zone. Oil consumption — another of the engine’s many weaknesses — would increase, accelerating the overheating process. It was like what happened after the Titanic hit the iceberg, when the first “water-tight” compartment filled up and dumped seawater into the next “water-tight” compartment.

As the Vega’s engine ran ever hotter — and began to shake ever more violently — coolant would seep into the liner-less cylinders. Where it would quickly cause catastrophic damage — coolant not being particularly lubricious. And because the engine wasn’t sleeved, a head gasket leak was usually fatal. The now-badly scored block was a throw-way.

Many buyers soon felt the same way about the Vega.

As a writer for Cars magazine put it:

“Tests which should have been done at the proving grounds were performed by customers, necessitating numerous piecemeal ‘fixes’ by dealers. Chevrolet’s ‘bright star’ received an enduring black eye despite a continuing development program which eventually alleviated most of these initial shortcomings.”

Emphasis on eventually.

GM didn’t do anything about the Vega engine’s fundamental design defects until the 1976 model year when a redesigned (and renamed) “Dura-Built” version was introduced. It had revised cooling passages in the block, a new design cylinder head, a redesigned water pump and valve stem seals that reduced oil consumption by 50 percent. This engine did not vibrate excessively or overheat. GM was so eager to prove the point it conducted a very public endurance test under the auspices of the United States Auto Club (USAC) in which three production-stock Vegas were driven non-stop for 60,000 miles through the scorched earth deserts of Nevada and California by teams of nine drivers in shifts, who covered nearly 200,000 miles in total. None of the cars overheated. None sucked coolant into the cylinders. Oil consumption was just one quart every 3,400 miles — high by modern standards, but a huge improvement over the original Vega engine’s one quart every 1,500 miles or so.

GM was so confident about the Dura-Built, it offered buyers a then-unheard of five year, 60,000 mile warranty.

But it came out four years too late.

Popular Science

Buy New $15.00

(as of 11:14 UTC - Details)

Popular Science

Buy New $15.00

(as of 11:14 UTC - Details)

Both the warranty and the Dura-Built engine.

If both had been standard equipment the first year of the Vega’s production life, its story might have been one of great success rather than epic failure — and lingering embarrassment. Instead, GM management — frantic to get their new economy compact on the market ahead of rivals (specifically, the Japanese — who had already established a beachhead and were rapidly moving inland) released the car before it was ready for prime time — and then spent years dodging what the company ought to have been fixing.

Ironically, Ed Cole was a top-drawer engineer, the man who oversaw the development of the original small-block Chevy V8 — one of the most successful and enduring designs in automotive history (the engine was first offered for sale in ’55 Chevys and continues to be produced to this day). But by the late ’60s, Cole had become management — and his agenda was making money, not designing a good engine.

It would end up costing GM a fortune — and Cole his reputation.