Thousands of Americans have just staged a demonstration in Washington, D.C., to express their displeasure with the growth of government in general and the Obama administration’s health-insurance proposals in particular. Such demonstrations are a tradition in this country. The First Amendment, which people usually associate with freedom of speech, religion, and the press, also stipulates that Congress shall make no law abridging “the right of the people peacefully to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” The Founders knew that people would sometimes desire to complain publicly against government policies that affected them adversely. After all, their own revolution had begun amid many such protests against the British government.

So, in this country, people have a constitutionally guaranteed right to demonstrate and petition for redress of grievances, and they often exercise this right. Although the government sometimes tries to control when and how people demonstrate, especially when such protests might prove too visibly embarrassing to the emperor or to one of the two gangs that purport to be competing political parties in what is actually a one-party state, most of the time the rulers seem to appreciate that such demonstrations pose no genuine threat to their control of the state and that the wise course is to allow the peasants to blow off steam. Later, they can be told how fortunate they are to live in a country where the government permits freedom of speech, as if such speech in itself would feed the baby.

Depression, War, and C...

Best Price: $3.05

Buy New $16.97

(as of 04:55 UTC - Details)

Depression, War, and C...

Best Price: $3.05

Buy New $16.97

(as of 04:55 UTC - Details)

I have considerable experience as a demonstrator. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, I marched and otherwise participated in many protests against the U.S. war in Vietnam. Although I managed to get through all these experiences without getting my head scarred by a police night stick — an achievement of which many of my fellow demonstrators cannot boast — I did learn a fair number of lessons in what we might call “applied political science.”

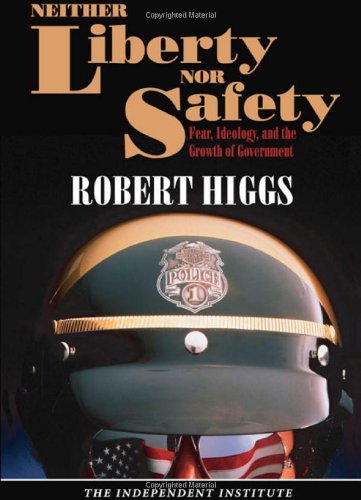

Neither Liberty nor Sa...

Best Price: $3.99

Buy New $10.00

(as of 05:35 UTC - Details)

Neither Liberty nor Sa...

Best Price: $3.99

Buy New $10.00

(as of 05:35 UTC - Details)

Lesson number one is that the cops do not believe in your First Amendment rights, or any other rights of yours, for that matter. If they find it convenient for their own purposes, which often seem to include nothing more than throwing their weight around, they will yell at you, shove you, threaten you with night sticks, dogs, and horses, whack you with their clubs, and lob tear gas into your ranks. It’s all in a day’s work for those who have sworn “to serve and protect.” Best you remember, however, that the phrase is short for “serve and protect the state,” not for “serve you and protect your rights to life, liberty, and property.” Protecting your right to demonstrate peacefully against state policies is not part of the cops’ job description.

Lesson number two is that the people in the demonstrations are there for all sorts of reasons, despite what one might suppose from their announced issue(s) as signified by signs, banners, and group statements. I often bemoaned the lack of seriousness in many of the antiwar demonstrators with whom I marched. A great many of the younger ones seemed to be there mainly because demonstrating against the war was, literally, a sexy thing for a college student to do: at the demonstration, one might meet someone suitable for a not-very-subsequent sexual liaison — in plain language, participating in a demonstration served as a reasonably promising avenue to getting laid. Beyond this quite understandable motivation, however, people had all sorts of other reasons for participating. Some fancied themselves radicals out to overthrow the government. Others were worried that children, grandchildren, or other relatives and friends might be drafted, shipped to Vietnam, and killed. Some of us actually cared about the countless hundreds of thousands of Asians being slaughtered by U.S. forces for no good reason. Although we were all against the war in some way, our ways varied widely. The participants in most demonstrations, including the recent one in Washington, no doubt have this same heterogeneous quality. In a protest, however, the enemy of my enemy is my friend.