Ken Rogers of Washougal, Washington was enjoying a visit with family in Kennewick and looking forward to some fishing when his slumber was rudely disturbed on the night of July 13, 2003.

Rogers, a 54-year-old regional sales manager for Georgia-Pacific, was sleeping under the stars when a large dog suddenly vaulted over a wooden fence and sank its teeth into his left arm. Shocked and disoriented in the darkness, and not wearing his eyeglasses, Rogers struggled desperately to free himself from the dog, to no avail.

A voice from the other side of the fence informed Rogers that the dog was the property of the Kennewick Police Department’s K-9 Unit. u201CStop fighting the dog and I will release him,u201D yelled Officer Bradley Kohn. Rogers, understandably, wasn’t content to wait, and started punching the police dog — later identified as u201CDekeu201D — in the head.

Officer Kohn, along with Officer Ryan Bonnalie, tore down part of the fence. The two of them, along with Deputy Jeff Quackenbush, u201Centered the backyard and subdued Rogers,u201D as the excessively decorous language of a legal appeal filed by the officers describes the incident.

The TriCity Herald offers a more descriptive account: u201CDeke latched onto [Rogers] and in the struggle bit him several times on the hand, back, neck and face while three officers beat him.u201D Syndicated legal affairs columnist Jack Kilpatrick, citing an official report, offers another layer of relevant detail: u201COfficers Kohn and Bonnalie and Deputy Quackenbush struck Mr. Rogers with fists, knees and a flashlight, while Deke continued to bite and hold Mr. Rogers until Mr. Rogers was subdued and handcuffed.u201D

An even more candid description of the episode would be this: Ken was sleeping peacefully when he suffered a potentially lethal dog attack, and then was severely beaten by three armed men after they had vandalized his host’s property.

Supposedly, all of this was justified because the police were hot on the trail of a criminal suspect. One would presume that they were seeking a burglar, a rapist, or some other practitioner of criminal violence. One would be mistaken: The police officers who beat Ken Rogers had been summoned as backup by Sgt. Richard Dopke after he had spotted someone riding a mini-moped without a helmet or turning on the lights.

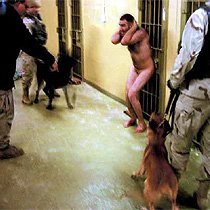

Overkill is always the first option: Sure, they’re heavily armed and already outnumber the protester, by why shouldn’t the riot police let their attack dog have a little fun, too?

Overkill is always the first option: Sure, they’re heavily armed and already outnumber the protester, by why shouldn’t the riot police let their attack dog have a little fun, too?

After Dopke turned on his siren and running lights and gave chase, the u201Csuspectu201D (whose behavior was foolish, but difficult to characterize as criminal) pulled into a nearby garage and shut the door. A man and two women at the residence, which was about a block away from the yard where Rogers was sleeping, claimed that the mysterious mini-moped rider named u201CTroyu201D had run half-naked through their backyard. Dopke later claimed that he didn’t find the story convincing, but he called for backup and a K-9 Unit just the same.

The story gets even uglier from here.

As it happens, Gary Hilliard, a Corrections Officer (jail guard) for Benton County, was the man who sent Officer Dopke off in pursuit of the mysterious moped man. And, it should not surprise us to learn, it was Hilliard who had actually been operating the vehicle illegally. Making matters all the nastier is the fact that roughly two years after this episode, Hilliard was fired from his job and served a three-month jail term u201Cfor having sexually explicit pictures of children on a personal computer,u201D reported the TriCity Herald.

I’m on record expressing misgivings about the way evidence is collected from computer hard drives in child pornography cases. I will point out that Hilliard’s subsequent record does cast his actions on the night of July 13 in an interesting light.

Just as it was overkill for the police to beat someone suspected of a minor traffic infraction, Hilliard’s actions in lying to the police and sending them after a fictitious fugitive could be seen as the product of a bad conscience. This makes me wonder if Hilliard was returning from an illicit assignation of some kind when he provoked the interest of Officer Dopke. In any case, Hilliard misdirected the police, and an innocent man was mauled by a police dog and severely beaten by several officers as a result.

Despite having to empty his bank account to pay for three months of physical therapy following the beating, Ken Rogers would most likely have let the matter go had the Kennewick Police Department displayed minimal decency and professionalism by contacting him, asking after his health, and expressing its regrets.

So Rogers sued the Kennewick Police Department for more than $2.35 million, complaining that he had been subject to illegal arrest, unreasonable search and seizure, and other violations of his individual rights.

En route to that verdict, the Kennewick city government made a ridiculously low settlement offer, called into question the extent of Rogers’ injuries (subtly accusing him of fraud because he wasn’t visibly disabled and continued to enjoy outdoor activities), and filed a petition to the US Supreme Court (.pdf) breathtaking in its assertions of official police impunity.

The petition was filed following a ruling from the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals last August that found Rogers had been subject to unlawful search and seizure. Seeking to overturn that ruling, attorneys for the Kennewick police claimed that Deke the police dog — not Officer Kohn, the dog’s handler — was responsible for the injury to Rogers.

Don’t blame me — it’s the dog’s fault: Heroic Military Police use dogs to threaten helpless Abu Ghraib detainees.

Don’t blame me — it’s the dog’s fault: Heroic Military Police use dogs to threaten helpless Abu Ghraib detainees.

Kohn claims to have released Deke after the dog’s leash had become entangled u201Con the hitch of a boat traileru201D in a driveway near the yard where Rogers was sleeping. Deke then vaulted the fence sua sponte and latched on to Rogers’s left arm. Because Kohn did not specifically order this assault, the police petition claimed, he did not intentionally u201Cseize anyone in the fenced backyard,u201D and thus there was no violation of rights protected by the Fourth Amendment.

According to the petition, u201Cthere can be no constitutional violation for a wrongful seizure where there is no intent to seize.u201D

Even if there were true regarding the attack by a trained police dog who was trained to act like (in the words of Diehl Lettig, Rogers’ attorney) a u201Cheat-seeking missile,u201D the fact remains that Rogers was swarmed, beaten, and handcuffed by three police officers.

This is an intentional u201Cseizureu201D by any rational definition. In fact, one of the federal District Court rulings cited in the police petition, Cardona v Connolly, actually vindicates Rogers’ complaint. That ruling held, in relevant part, that a u201CFourth Amendment seizureu201D can be said to take place u201Conly when there is a governmental termination of freedom of movement through means intentionally applied.u201D

Surely the liberal use of u201Cfists, knees and a flashlightu201D by police against a prone individual being mauled by a police dog until the victim is u201Csubduedu201D and handcuffed would qualify as u201Cgovernmental termination of freedomu201D through u201Cintentionalu201D means.

“Qualified immunity,” reduced to its essence.

“Qualified immunity,” reduced to its essence.

Nonetheless, the petition for US Supreme Court review filed on behalf of the officers insisted that their actions were covered by the principle of u201Cqualified immunity,u201D which is described as u201Can important constitutional protection for our public servants.u201D

u201CGovernment officials performing discretionary functions are entitled to qualified immunity, shielding them from civil damages liability as long as their actions could reasonably have been thought consistent with the rights they are alleged to have violated,u201D insists the Kennewick police brief.

What this means, from that perspective, is that the police had an open-ended and unqualified right to beat and detain Rogers unless he can (quoting again from the brief) u201Cdemonstrate that the police officers, by their conduct, violated a clearly established constitutional right….u201D Furthermore, it wouldn’t do, insisted the police petition, for Rogers to demonstrate the violation of u201Ca generalized right, such as the right to be free from illegal searches or seizures or the right generally to be free from the excessive use of force.u201D

In this specific case, the police argued that unless Rogers, could prove that Officer Kohn intended for Deke to attack him specifically, he had no legal recourse. On this construction, the mauling, beating, handcuffing, and general mistreatment Rogers endured was all legal and appropriate, since those who inflicted it on him were clothed in u201Cqualified immunity.u201D

Fortunately, this matter ended up being put before a jury of sensible people who detected in that argument the distinctive aroma of something very much like the sort of residue Deke deposits at the end of his canine digestive cycle.

A significant and relevant post-script to this matter:

Three of those implicated in this incident — Officers Dopke and Bonnalie, and Deke — were retired form the force between 2003 and 2006.

Officer Bonnalie, who helped vandalize the fence and had a hands-on role in beating Rogers, was fired in 2005 after an off-duty road rage incident in which he threatened a 63-year-old Meals on Wheels volunteer by shoving a handgun into his chest.

A parting thought…

Several people whose opinions I highly esteem and whose friendship I cherish have advised me to “balance” my reporting on the police. They have a sound point; I don’t want to become monomaniacal on the subject of police corruption. I am searching for suitably inspiring stories about good police officers and willing to run them when given the chance. And I am always receptive to news tips about stories of that kind (or any other, for that matter).