Salt Lake City’s Deseret News, as part of its continuing campaign against rationality, recently published a house editorial condemning civilian ownership of firearms.

Bobbing in the puddle of pathos created by the editorial staff’s lachrymosity can be found this lump of congealed hypocrisy: “[T]ough guys don’t pack firearms. Fearful guys do — people who see everyone around them as a threat and think the worst of faces they don’t recognize. Guns don’t showcase strength, they showcase weakness.”

There is the beginning of an important point here, but it’s one the people responsible for that editorial, in their ideologically induced foolishness, are too thick to recognize: If they are serious in their assessment that carrying firearms (particularly handguns) is symptomatic of socially dangerous insecurity on the part of those who carry them, then disarmament should begin with those most frequently found in public possession of those weapons — that is, the police.

Since police are trained “to see everyone around them as a threat and think the worst” of those they encounter, they are a uniquely suitable target for disarmament, at least by the standard suggested by the Deseret News.

In what could be (depending on one’s worldview) either a divinely ordained symmetry, an example of Karmic synchronicity, or a convenient coincidence, an active-duty police officer validated the point above in a brief blog item for National Review.

Writing about the arrest of Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr., “Jack Dunphy” — the name is a pseudonym for an active-duty LAPD officer — took umbrage with the suggestion that slapping a set of handcuffs on a small, middle-aged man and hauling him off to jail might not be the wisest way for a police officer to react when offended by something that man had said.

After all, insisted the cyber-Centurion, being a policeman is dangerous, and those mundanes who refuse to display proper docility might well end up dead.

By way of illustration, “Dunphy” writes, “here is what I would advise [anyone] … who finds himself unexpectedly confronted with a police officer: You may be pure as the driven snow itself, but you have no idea what horrible crime that police officer might suspect you of committing. You may be tooling along on a Sunday drive in your 1932 Hupmobile when, quite unknown to you, someone else in a 1932 Hupmobile knocks off the nearby Piggly Wiggly. A passing police officer sees you and, asking himself how many 1932 Hupmobiles can there be around here, pulls you over.”

The Emerging Police St...

Best Price: $3.75

Buy New $16.95

(as of 06:25 UTC - Details)

The Emerging Police St...

Best Price: $3.75

Buy New $16.95

(as of 06:25 UTC - Details)

“At that moment,” Dunphy continues, “I can assure you the officer is not all that concerned with trying not to offend you. He is instead concerned with protecting his mortal hide from having holes placed in it where God did not intend. And you, if in asserting your constitutional right to be free from unlawful search and seizure fail to do as the officer asks, run the risk of having such holes placed in your own.”

Are you paying attention, oh wise and compassionate editorial board of the Deseret News? Here is an active-duty police officer who treats as a virtue precisely the cluster of borderline-paranoid traits you ascribe to every civilian gun owner: A tendency to see everyone else as a threat, an inclination to suspect the worst of every stranger, and a willingness to resort to lethal force at the slightest provocation.

From the point of view of that police officer — a very common opinion in that profession — killing an innocent civilian as the result of a mistaken threat assessment, however tragic, is justifiable.

In fact, summary execution just might be condign punishment for a mundane who “disses” a police officer by being a bit too persistent in asserting his rights, according to “Dunphy.” He and the others of his caste enjoy the privilege to kill, which means that the rest of us have a duty to submit, or die.

So when an innocent person finds himself on the receiving end of unjustified attention from a police officer, his only safe course of action — from this point of view — is that of the proverbial rape victim: Just lie down and endure it, and enjoy it, if possible.

“One of the common-sense rules of life can be summed up this way: Don’t mess with cops,” opined Washington Post writer Neely Tucker by way of reinforcing that point in the aftermath of the Gates arrest. “It doesn’t matter if you are right, wrong, at home or on the street, or if you are black, Hispanic, Jewish, Muslim or whatever,” Neely asserts. “When an armed law enforcement officer tells you to cease and desist, the wise person (a) ceases and (b) desists…. The police, when they show up at a residence or a liquor store, don’t know what’s what or who’s who. The good cops are there to have people (a) cease and (b) desist. The bad cops still have a badge, a gun and the legal authority to haul your butt downtown.”

“So you want to make friends, join the glee club,” concludes Neely. “You want to yell at people who are lousy at their jobs, go to a Redskins game. But, all things considered, don’t mess with cops. It usually works out better that way.”

Here’s how it breaks down from the statist perspective: When civilians carry firearms because they don’t know who the bad guys are, we’re being pathologically insecure; when police not only carry them but routinely use them to make others submit to their will without reasonable cause, they’re merely exercising a professional prerogative.

As things presently stand, any reaction to police other than immediate, unconditional submission is treated as a threat to “officer safety” and grounds for arrest or the exercise of lethal force. “The rule is, if a police officer stops you in a car or on the street, he’s the captain of the ship, and whatever he says goes,” insists Jim Pasco, executive director of the Fraternal Order of Police. “If you’ve got something to address, do it later. Do what he says, or else only bad things can happen.”

Do what he says, or else only bad things can happen.

Isn’t that the essence of any illicit demand made by a criminal or terrorist?

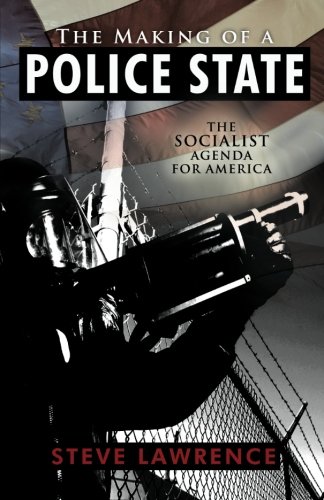

The Making of a Police...

Best Price: $18.39

Buy New $23.95

(as of 01:45 UTC - Details)

The Making of a Police...

Best Price: $18.39

Buy New $23.95

(as of 01:45 UTC - Details)

Pasco and others of his ilk display a mindset that is innately, and definitively, anti-American. Not only do they assume that were living in a state akin to martial law — that is, a condition in which civilians are required, on pain of death, to render immediate obedience to people in state-issued costumes; they also assume that authority flows downward from government officials upon the heads of less exalted personages in the private realm.

Norm Stamper, former police chief of Seattle, Washington, is a retired peace officer whose influence is sorely needed today. He points out that contemporary law enforcement officers are not trained to deal respectfully and deferentially to “real Americans” — that is, people who understand that in our constitutional system police are supposed to be their servants, not their masters.

“Any cop can deal with a robbery suspect, but show me the cop who can handle a real American,” commented Stamper in a recent interview with the (Boston-based) Christian Science Monitor, quoting policing expert George Thompson. A “real American” is “someone, when you say, ‘Roll down the window,’ says ‘No,’ or who meets you at the threshold at home and says ‘No, you can’t come in. Show me your warrant.'”

For all of the horrors associated with the militarization of law enforcement, there is one ironic benefit: It’s becoming easier all the time to recognize the “real Americans” among us. They’re the ones writhing at the end of Taser wires, or being dragged away in handcuffs, or bleeding to death on the floor of their homes because they required — either verbally or through so much as a moment’s puzzled non-cooperation — a modicum of respect for their constitutionally guaranteed rights.

Most jurisdictions have what some call “cover laws” — such as those dealing with “disturbing the peace,” “disorderly conduct,” or other dubious infractions — that are applied with malicious creativity by police officers who don’t care to be reminded of their servile status.

It’s not unusual for police officers possessed of a particularly strong bullying tendency to bait citizens into conduct that can be described as “disorderly” in order to create a pretext for arrest. That’s pretty clearly what happened in the Gates arrest.

David Rudovsky, a senior fellow at the University of Pennsylvania Law School, describes the phenomenon of “persons being arrested who challenge the authority of police” as a form of extra-judicial “street punishment.” That is to say, it’s exactly the kind of government-inflicted criminal violence that provokes official disapproval in State Department-issued human rights surveys of other countries. By now it’s become pretty clear that issuing reports of that kind is a motes-and-beams exercise.

Perhaps there’s nothing new about the common “wisdom” urged on us by our rulers, who expect us to behave like cringing serfs in every encounter with our supposed protectors — and then to hymn the praises of the “freedom” we enjoy as subjects of the world’s largest, most powerful, and most malignant empire.

What is new, and ominous, as illustrated by the Gates Incident, is this: Taken as a body (there are more than a few heroic and valuable exceptions), the federalized, militarized police “community” is a Praetorian Guard afflicted with a prickly pettiness about criticism, whether public or private.

Granted, America’s professional police forces were not originally created as a special bodyguard to the chief executive. But over the past four decades, since Richard Nixon announced a “war on crime” as a cynical ploy to capture the loyalty of the uniform-worshiping “Silent Majority,” all serious presidential contenders have courted the endorsement of police unions and associations. Each administration since Nixon’s has cultivated a bond between the “front-line soldiers in the war on crime” and their “Commander-in-Chief.”

Accordingly, police unions now have sufficient political influence — due in no small measure to the tendency of conservatives to fetishize armed bureaucrats in uniform — to stare down the President. Witness the success of Sgt. James Crowley, the officious dweeb who needlessly arrested Henry Gates, in extracting — with the help of his comrades in the police union — what amounts to an apology from Barack Obama.

Observed the Christian Science Monitor: “[T]he union’s hard line — successfully staring down a president — is a window into the so-called Thin Blue Line — the ‘Band of Brothers’ mentality that draws police departments closer in time of crisis.” Or, in this case, fuses them together in bonds of adolescent petulance in confronting their critics when one of their number abuses a citizen.

We’ve reached the stage in our imperial decline in which the bearer of the Imperial Purple has to take care to keep the Praetorians on his side. Obama is particularly vulnerable in this respect, not only because police unions see him as a cultural outsider but especially because his agenda for forcible reconstruction of American society will depend heavily on the organs of official coercion.

As someone who lives inside an all but impregnable security bubble, Mr. Obama doesn’t face the prospect of sudden, undeserved violence that increasingly haunts typical citizens in their encounters with police. Yet in his recent stand-off with Officer Crowley and his comrades in blue, Obama flinched because he obviously fears the political consequences of alienating the Praetorians.

Liberty in Eclipse

Best Price: $10.58

Buy New $57.61

(as of 09:10 UTC - Details)

Liberty in Eclipse

Best Price: $10.58

Buy New $57.61

(as of 09:10 UTC - Details)

A piece of American folk wisdom unwisely attributed to Thomas Jefferson informs us that when government fears the people, there is liberty. As our present and deepening predicament indicates, this isn’t entirely true.

Those supposedly intrepid fellows who are kitted out in high-powered weaponry and body armor, and prowl our cities in over-powered cars, have a bladder-loosening fear of the common citizenry. The worst among them are bold as Achilles when it comes to slapping the cuffs on diminutive Harvard professors, or forcing grandmothers to do the “electron dance,” but suddenly acquire a taste for caution when dealing with actual criminals who can put up an effective resistance.

At some point, common Americans — both inside and outside the jury box — are going to have to rediscover the ancient and indispensable right to resist unlawful impositions by police. We need to bring about an end to the culture of impunity that has taken root and begun to flourish in law enforcement.

The best way to do this is not by trusting police to police themselves, or expecting the political class to do likewise, but to recognize, in law and practice, a principle articulated centuries ago by John Locke: A criminal who acts under the color of government “authority” is simply a criminal, and should be dealt with, by the citizen, in appropriate fashion.