Nobody Knows What a Landlord Is

Keep Henry George's Name Out Of Your Mouth

January 19, 2026

The Landlord Question

Everything needs to be somewhere. This physical space, this fact of nature, we call “Land.” People who own land, we call landowners. People who earn income from letting people use land, we call landlords. Landlords get a bad rap, probably since the first tenant learned how to write.

When modern progressives rail against landlords, even Austrians finds themselves in an unprecedented position. Consider the normal path of discussions with non-economists. Free trade is possibly the oldest and only economic consensus. Paul Krugman is in favor of Free Trade, and so was Karl Marx. If someone calls for tariffs or an inflationary monetary policy, the dilettante inevitably cites John Maynard Keynes at best and at worst an anonymous mass of econometric studies which do not and cannot disprove economic laws. Rent control? Even a first year economics undergraduate can draw a simple supply and demand curve, draw a price line below the intersection, and explain the problem.

Not so when someone rails against the very existence of private land ownership. Suddenly, our foes can cite the world before the McKinley administration. Suddenly, they can draw on the entire corpus of classical economics. The hatred is staggering in its consensus. Mao hated landlords, obviously, so did Marx, and so did a guy named Henry George. With growing confidence and growing strength, they cite Hume, they cite Smith, they cite Ricardo. Suddenly the Austrian must admit that he never really liked Adam Smith anyway. Suddenly, the proper arguments were only ever made in 1940 in Nationalökonomie, first translated into English in 1949 as Human Action.

Like “inflation”, the meaning of the “landlord” has shifted out from under the word, obscuring more than it reveals. Inflation once referred to expansions in the money supply, which in caused a increase in prices. Soon, inflation referred to the increase in the price level, its root cause suddenly a mystery. Capitalist originally meant “one who has large property employed in business”. Then it came to mean simply “a person who believes in the private ownership of producers goods,” whether such a person was themselves owner or not.1

To understand what has happened, we must distinguish the “Classical” Landlord from the Modern “Landlord”.

The “Classical” Landlord

The “Classical” Landlord, as understood by Smith, Ricardo, Marx, and George was just that, a feudal lord or a relic thereof. The traditional feudal relationship of kings, lords, knights, and serfs came increasingly out of fashion in the fifteenth century. This process had began as early as the Black Death of 1348 and the ensuing Peasants Revolts of 1381, after which desperate lords had begun to commute labor service (serfdom) into money rents (tenant farming). In 1660, England’s Tenures Abolition Act formally abolished knight service and other feudal dues, converting all such obligations into simple money payments.

This development was also co-incident with the enclosure movement. Originally, millions of acres outside of feudal holdings were held as “Open Fields” (farmed in long, narrow strips by individual peasant families) and “Common Land” (freely available for grazing livestock and gathering firewood). In a process of dubious legality even in the 1400s, lords, gentry, and more well-to-do peasants began to simply enclose open fields and common land en-masse with their own fences in order to graze sheep on the arable land. Entire towns, suddenly cut off from their food supply, were depopulated. From 1600 on, Parliament began passing “Inclosure Acts”, granting property to these lands to manorialists and other politically connected people who had never worked the lands nor even allegedly owned them under feudalism, rather than to the peasants who had been inhabiting and working those lands for centuries.

This is the context behind John Locke’s 1690 proposal of the Homestead Principle, by which property could only be justly acquired by “mixing labour with” the land. He was seeing a series of fiats by which otherwise unowned, unimproved, and in some cases uncharted land worked by peasants suddenly became private property of an aristocrat once the latter wanted to get into the shepherding business or noticed all of the productivity suddenly going on outside of his estate. The Homestead Principle was inverted into “adverse possession” law. Instead of granting possession to the original occupant, aristocrats were granted original title on a “use it or lose it” basis. If a peasant still managed to work a plot for twenty years straight without anybody even noticing, the peasant had a claim superior to the putative legal owner of the plot. This small mercy has today been grotesquely perverted yet further into so-called “squatters rights” law, where someone can rent an AirBNB for 30 days, refuse to vacate, and be legally protected from immediate eviction on the grounds that they were a contractually recognized occupant of the dwelling.

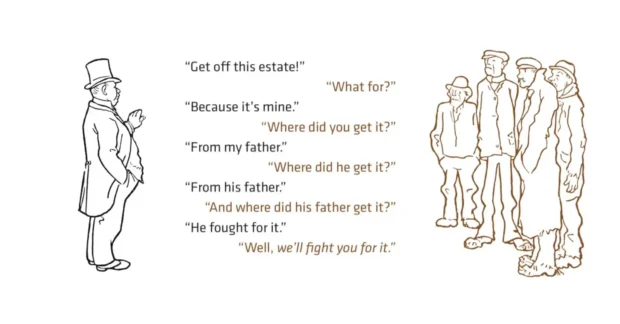

These are the landlords the classical economists were talking about. They owned large estates, encompassing multiple towns and all the forests and fields in between, as a relic of feudalism. The land was granted to an ancestor of his, as a reward for earlier service to the sovereign, with the promise of an eternal right to extort the peasants. In the case of England, that service was the act of subjugating and enslaving the English people themselves under the yoke of their new Norman overlords. This distinct from the accusation that America is on stolen land. While America did trick, trap, rob, wreck, butcher, and murder the natives, the seized land was immediately set upon not by extractive aristocrats but by productive homesteaders. This doesn’t make the land not stolen, but it’s easy to see why self-interested Anglo-Americans could convince themselves of a morally relevant difference.

The “Classical” Landlord owns only the land, not things on it. He doesn’t improve the land, he rents it out to peasants. If peasants choose to carry out improvements, whether building homes, developing farms, draining swamps, clearing forests, or starting businesses, then the landlord observes the fruits of his efforts, assesses the former swamp as more valuable than it was before the farmer drained it, and increases the farmer’s rent accordingly. The reward for improvement is more rent, and if the farmer doesn’t like it, he can leave his home, extended family, and church behind.

If an industrialist builds a factory on land owned by a “classical” landlord, the classical landlord can, will, and must raise rent on him until the factory shuts down. This is first because the industrialist on the “classical” landlord’s land is competing with the landlord himself for access to labor, as the industrialist can pay the tenant farmers a proper wage. This is second because the landlord cannot know how profitable the new enterprise is, since entrepreneurs operate from uncertainty about the future and are quite skilled at obscuring the revenues made in the past from authorities, so the the landlord cannot calibrate his rental demands to any degree but “more”.

Land being a gift of nature, and with his claims built on parliamentary fiat at best and imperial subjugation at worst, these people were rightly seen as wholly parasitic. He is essentially a tax collector. Depending on the time and place, this aristocrat may well have been a literal hereditary bureaucrat, and “land-based taxation” in his day amounted to subcontracting tax collection of his peasants to him. Any increases in his standard of living do not come from any savings, investment, labor, or entrepreneurial alertness on his part, but from the people on “his” land taking the initiative to improve that land, or else simply increasing in population for him to extort.

That parasitism, combined with the inherent absurdity of the landlord’s original claim, is why progressive movements promise land reform. Such promises invariably imply a return to the Homestead Principle, stripping land from parasitic “owners” and granting the title to the tenant farmers. The Landlords in such countries then complain to Americans that abolishing their literal feudal privilege is tantamount to Maoism.

Indeed, when communists promise land reforms, what they actually deliver is not homesteading but collective farming. Consider “Dekulakization,” otherwise known as the Holodomor. Why did Stalin hate Kulaks? Because a prior land reform at the end of the Tsar’s reign had granted tracts of Ukrainian land to its rightful peasant owners. Their rights respected, they had become successful, in many cases hiring people to help them work their homesteads. These folk had become particularist at best, meritocratic and reactionary at worst. They had no need for the Party of Lenin and Stalin, so Stalin had no need for them. Thus, the successful land reform based on the Homestead Principle and the abolition of feudal privilege was undone, and the land was “collectivized” under a new landlord in the form of the Soviet state. This was not just under Stalin. At the exact same time, those American homestead farms build on stolen Native American land were being Agriculturally Adjusted into oblivion by the Roosevelt Administration, passed into the hands of large, politically connected agribusinesses under a “modern” commercialized agriculture system.

But Land Reform is good. Land Reform, what is described as “taking land from the big landowners and giving it to the peasants” is an unalloyed presumptive good, a basic component of moral justice and the transition out of Feudalism. You are not “taking land” from “big landowners”, you are recognizing the wholly legitimate property rights of the people who actually use and improve the land.2 You should not roll your eyes when you hear people talking about it, you should not (immediately) think of it as some communist wealth redistribution program.3 The Libertarian response to these feudal “property claims” is to dismiss them with prejudice. “I don’t care if Boleslaw the Brave granted your great grandfather the fields and the trees nine hundred years ago. That’s not a property claim, that’s not anything.”

Copyright © Marcel Dumas Gautreau