Regenerative Medicine and The Cell Danger Response

How locally resolving the cell danger response allows chronically impaired tissues to heal and resume their normal function

February 10, 2026

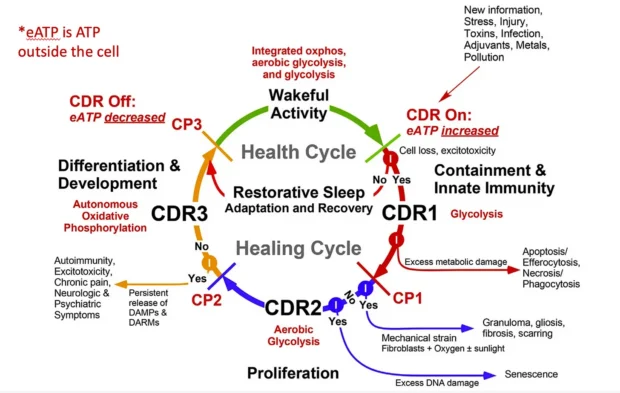

In the first part of this series, I introduced Robert Naviaux’s concept of the Cell Danger Response (CDR), a primitive defensive mechanism cells enter in response to environmental stressors. The CDR is orchestrated by the mitochondria, which switch from a metabolic type that produces energy that sustains the cell to a metabolic state focused on defending the cell (thereby making the cell much more resistant to otherwise lethal injuries). Once the CDR is activated, the cell enters a partially dormant state (as many cellular functions depend upon the regular activity of the mitochondria) and signals other cells in its vicinity to also enter the CDR.

Ideally, the CDR should proceed through three phases (with the third, CDR3 being where the cell reintegrates with the body) and then terminate. Unfortunately, it often fails to do so, leaving the cells in a chronically impaired state where they are disconnected from the body.

Although the protective role of the CDR has a vital role in sustaining life, in the modern age, people frequently are exposed to a volume of stressors that significantly exceeds what the CDR originally evolved to handle. This results in a chronically activated CDR, which in turn gives rise to a wide range of chronic and complex illnesses.

Men’s Daily Mult...

Buy New $19.97

(as of 05:34 UTC - Details)

Men’s Daily Mult...

Buy New $19.97

(as of 05:34 UTC - Details)

The medical field (particularly those practicing integrative medicine) has become more and more open to the idea that mitochondrial dysfunction is the root cause of many illnesses. The CDR provides important context to that paradigm, as it illustrates mitochondrial dysfunction is not something that “just happens” and needs to be treated with supplementation; instead, it often needs to be viewed as an adaptive response, and to treat the mitochondrial dysfunction, the CDR itself must be the focus of treatment.

My focus was drawn back to the CDR after I realized that the most effective treatments I had found for spike protein injuries (e.g., within minutes, they created a dramatic shift in the well-being of the patient—in some cases restoring functionality which had been lost for months) worked by either repairing the zeta potential of the body or treating the cell danger response. In turn, I’ve come to believe these are two of the primary issues in patients with spike protein injuries (along with other vaccine complications like autism).

Unfortunately, while the CDR provides an excellent framework for understanding complex illnesses, the available tools for treating the CDR are still quite limited and require a comprehensive understanding of the CDR to use correctly. Fortunately, another field, regenerative medicine, regularly works with dormant cells and has found a variety of ways to reactivate them.

Note: no model in medicine is perfect. In the case of the CDR, I frequently observe cells in a state resembling that produced by the CDR, which I believe are being affected by something else, and likewise, other medical models I employ in practice have different frameworks to describe this general cellular inhibition. However for brevity, I use the phrase “CDR” to describe many of the degenerative processes which produce chronic disease.

Surgery and Regenerative Medicine

Often, we run into the problem that a part of the body doesn’t work right (to the point it significantly impacts someone’s quality of life), and the only available option to address the issue is a surgical procedure. Unfortunately, surgeries often fail to fix the issue (or only offer a temporary alleviation) and, in many cases, have significant complications that are much worse than the original issue.

Note: spinal surgeries are among the most problematic surgeries, and unfortunately due to their lucrative reimbursement, are often pushed on patients who will not benefit from them (discussed further here).

In turn, I regularly meet people who state they wish they had never had a surgery they received. I thus am always looking for ways to undo the side effects of surgeries (unfortunately, many are permanent), seeking out competent surgeons to send patients to (as there is immense variability in outcomes depending on who does a surgery), and always questioning which surgeries are actually necessary or provide a net benefit to the patient.

Some of the complications from surgeries are very easy to recognize (e.g., chronic spinal pain worsening after a spinal surgery), but many others are far more subtle and difficult to recognize. For example, over the years, we’ve noticed one function of the appendix is to keep cells out of the CDR, and as a result, we’ve observed autoimmune disorders (e.g., in the thyroid) onset after appendectomies and a gradual decline in the functionality of the body matching that seen in aging as more and more cells enter the CDR.

Note: while I believe the risks of many surgeries greatly outweigh their benefits, I very much support certain ones (e.g., laminectomies for a spinal nerve being compressed by bone). Conversely, there is a wide range of issues with what surgeries do to the body that few people (including most surgeons) are even aware of. For this reason, I am relatively conservative in recommending surgeries.

Fortunately, there are often superior alternatives to surgery, many of which come from regenerative medicine. Many of these come from the field of regenerative medicine. Regenerative medicine is typically associated with “stem cell therapy” and encompasses a broad range of therapies, including:

• Neural Therapy

• Prolotherapy

• Prolozone

• Placental Extracts

• Extracellular Matrix Materials

Men’s Daily Mult...

Buy New $19.97

(as of 05:34 UTC - Details)

Men’s Daily Mult...

Buy New $19.97

(as of 05:34 UTC - Details)

• Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP)

• Exosomes and Stem Cells

• Energy therapies directed at weakened tissue.

• Electrical or ionic stimulation of tissue (this method was pioneered by orthopedic surgeon Robert Becker to heal non-healing tissue and bone).

Note: while these treatments are often incredible (e.g., PRP accelerates the healing of fractures and can often heal a wide range of tears—particularly those in areas with a poor vascular supply that prevents them from healing otherwise), it is very common for excessive doses to be given, which trigger rather than resolve the CDR or leave patients with months of inflammation afterwards (in part because of the inherent incentive to sell these profitable therapies to patients). Additionally, the benefits obtained are highly dependent on which version of a therapy is used (e.g., many cheaper PRP kits do not work as consistently). Finally, since many of these treatments provoke an inflammatory response as part of the healing process, care often has to be taken with giving them to certain populations like Covid vaccinated patients (e.g., by giving lower doses) as greater inflammatory responses can occur in them.

These treatments are typically applied with minimally invasive targeted injections, although some are directly implanted during surgery, some are used as topical patches, and some are injected intravenously. Since the most common application for regenerative medicine is as an alternative to orthopedic surgeries (e.g., a knee replacement or a shoulder repair) many of these therapies are used by orthopedic surgeons.

There are thus two ways regenerative medicine can be practiced:

• As a protocol-based approach where regenerative therapy is directly administered to an injury, the existing evidence states it can help (with PRP being one of the best examples).

• As a system that tries to understand where cellular dysfunction is preventing health from emerging so the body’s momentum can be shifted back towards wellness and health.

I appreciate the first approach because it has allowed many to avoid surgeries (often also providing a much better outcome) and because its compatibility with the conventional medical paradigm has created an interest in developing and commercializing more and more regenerative therapies (along with developing a robust body of literature for the practice).

However, the second approach is where I often see miracles occur (e.g., restoring a failing organ that otherwise required a transplant or creating a life-changing restoration of functionality) and thus what I want to draw awareness to.

Integrative Regenerative Medicine

When the second approach is practiced, it requires determining why a failing tissue has not regenerated on its own—something that typically happens in the background without one’s knowledge due to the immense self-healing capacity of the body. This, in turn, requires assessing if the issue is the cells having turned off (e.g., they are no longer dividing) or if there is a lack of viable tissue that requires external replacement.

Additionally, regardless of which is the case (reviving existing tissue versus creating new tissue), achieving a consistent result with regenerative therapy also requires doing the following:

• Providing the nutritional support necessary for the tissue to heal or regenerate.

• Identifying and addressing what is preventing the system from healing (e.g., commonly the issue is insufficient circulation which cannot bring the tissue the nutrients it needs or drain the waste products which are interfering with healing).

• Identifying at the current time which area of the body will produce the most significant benefit from receiving a regenerative therapy, getting it to the target area, and knowing which regenerative treatment is appropriate to use at the time (rather than being too much for the moment), along with how the indicated therapy will change in the future.

• Using a good quality regenerative medicine product (e.g., many of the cheaper PRP kits do not work anywhere as consistently).

Understanding how to do each of these (discussed further here) requires a great deal of clinical experience, and I feel very fortunate to have spent years working with colleagues well-versed in all of it. One of the most important things I learned from my them is that, in the majority of cases, the primary issue is the cells having “turned off” rather than a lack of viable tissue (hence making the issue much easier to fix). The rest of this article will explore how pockets of cells turning off relates to the CDR.

Physiologic Weak Points

A common observation when treating patients with spike protein injuries is that pre-existing areas of weakness in the body (e.g., a site of recurrent inflammation or an old injury like a surgery) tended to be disproportionately affected by the vaccines.

Physician’s CHOI...

Check Amazon for Pricing.

Physician’s CHOI...

Check Amazon for Pricing.

This phenomenon was the first thing that clued me into how big of a problem the vaccines were going to become, as immediately after they hit the market, I began to have patients show up with searing pain at the sites of old surgeries or intermittent arthritis. Given that I had previously seen something similar happen to patients with Lyme disease (where the mantra is “Lyme first shows up in the weakest point in your body”), this was quite concerning to me.

Note: typically the issue was pain and a lack of function (e.g., many people shared an old scar they’d forgotten about was suddenly “on fire”) but in most extreme cases, I saw multiple instances where a tendon had previously been surgically repaired a long time ago rupture.

After I started investigating this more, I discovered rheumatologists and neurologists I knew were observing something similar. For example, in addition to the vaccines causing new autoimmune disorders, pre-existing autoimmune diseases frequently flared in vaccinated patients. I heard estimates ranging between 20-25% from (open-minded) colleagues in practice, and the most detailed study I came across, found 24.2% of patients with a pre-existing autoimmune disease experienced an exacerbation after receiving a booster (along with 26.4% of those with anxiety or depression—two other conditions linked to the CDR).

Note: another early red flag—friends and patients reporting sudden deaths after vaccination to me—started happening about a month into the vaccine rollout.

The rate of autoimmune complications is very high, and concerns about these effects have led to various hypotheses over why it is happening. The most common one is that the spike protein is inflammatory, something that, while correct, doesn’t explain the complete picture. Similarly, I previously put forward the theory that the spike protein’s ability to freeze fluid circulation in the body played a role as methods that restored that circulation (e.g., restoring zeta potential) either improved or resolved their symptoms.

However, I believe the CDR provides the best explanation for why all of this was happening.

Copyright © A Midwestern Doctor