To regulate itself, the body often relies upon sensors that detect something amiss and then emit a signal that is amplified by the body so that a process can be set in motion to fix the issue that set the sensor off. One of the key signals the body relies upon are hormones, as small amounts of these molecules being released are often sufficient to change the internal state of the body drastically.

Cancel Culture Diction...

Best Price: $1.72

Buy New $9.95

(as of 11:12 UTC - Details)

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is the body’s central stress response system. It has three main components: the hypothalamus and pituitary gland in the brain, and the adrenal glands on top of the kidneys. When you experience stress, the hypothalamus releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which signals the pituitary gland to secrete adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). ACTH then travels through the bloodstream to the adrenal glands, prompting them to release the corticosteroid cortisol (the body’s primary stress hormone). Finally, once cortisol levels are high enough, they signal the brain to reduce CRH and ACTH production, creating a negative feedback loop that prevents over-activation of the stress response.

Cancel Culture Diction...

Best Price: $1.72

Buy New $9.95

(as of 11:12 UTC - Details)

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is the body’s central stress response system. It has three main components: the hypothalamus and pituitary gland in the brain, and the adrenal glands on top of the kidneys. When you experience stress, the hypothalamus releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which signals the pituitary gland to secrete adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). ACTH then travels through the bloodstream to the adrenal glands, prompting them to release the corticosteroid cortisol (the body’s primary stress hormone). Finally, once cortisol levels are high enough, they signal the brain to reduce CRH and ACTH production, creating a negative feedback loop that prevents over-activation of the stress response.

Cortisol, in turn, has a few key functions in the body:

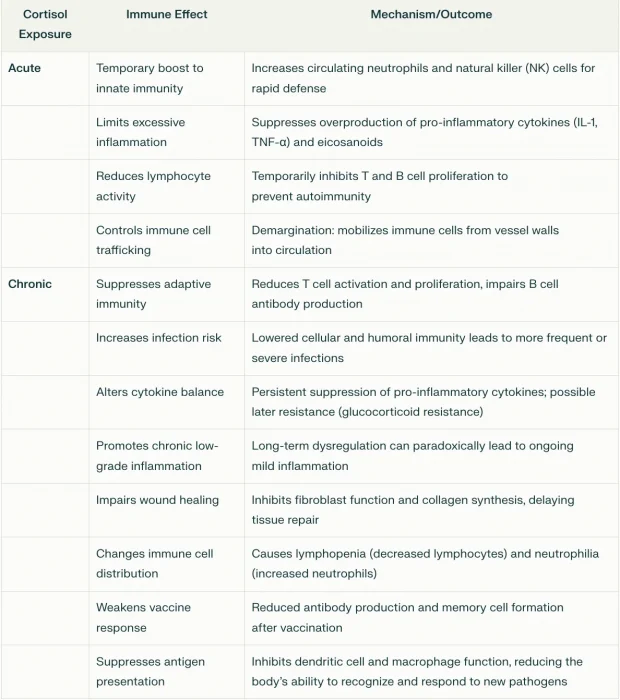

Immune Modulation: Cortisol first enhances the immune system’s immediate response to threats (protecting the body during stress), then limits excessive immune activity to prevent autoimmunity. It does this partly by inhibiting pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1, IL-6) and reducing T-cell activity. Over time, this shifts to immune suppression, making synthetic corticosteroids, a popular treatment for inflammation and autoimmunity.

Note: at lower doses, this transition from immune stimulation to immune suppression takes much longer, whereas at high doses it’s faster (hence why high steroid doses are given for dangerous autoimmune flares).

Blood Sugar: When blood sugar is low, cortisol raises it by stimulating gluconeogenesis in the liver, mobilizing amino acids (from muscle) and fatty acids (from fat) for glucose production, and reducing insulin sensitivity in tissues like muscle and fat. Excessive cortisol can lead to diabetes, abdominal fat accumulation (obesity), weight gain, insulin resistance, and cardiovascular issues.

Connective Tissues: Cortisol promotes protein catabolism (breakdown) in muscles, providing substrates for glucose synthesis and inhibiting collagen synthesis. Excessive cortisol causes muscle wasting, bone loss (e.g., osteoporosis or osteonecrosis), poor wound healing (which is also a result of immune suppression), skin thinning, easy bruising, and purple striae.

Circulation: Cortisol raises blood pressure by increasing sodium and water retention, sensitizing blood vessels to epinephrine and norepinephrine. This causes vasoconstriction and an increased heart rate while also damaging the blood vessel lining. This elevates the risk for cardiovascular disease1,2,3 (e.g., a one-standard deviation increase in morning plasma cortisol is linked to an 18% higher risk of future cardiovascular events).

Cognition: Cortisol modulates arousal, attention, and memory consolidation. Chronic excess corticosteroids (from either endogenous cortisol or synthetic steroids) impair hippocampal function, causing memory deficits, increased pain sensitivity, attention issues, cravings for high-calorie foods, substance abuse, and, rarely, psychosis.

HPA Axis Dysfunction: Since the HPA axis is regulated by cortisol levels, once natural or synthetic corticosteroids are chronically elevated, the HPA axis becomes desensitized, leading to excessive cortisol secretion or loss of the ability to secrete cortisol when needed. This in turn creates many issues such as those associated with chronically excessive cortisol or varying degrees of fatigue (e.g., due to the adrenal glands not secreting cortisol when needed).

Note: excessive cortisol can also cause other effects such as blood electrolyte imbalances, alkalosis, cataracts, and glaucoma.

Because of this, many argue excessive cortisol secretion and HPA axis dysfunction (e.g., due to chronic stress, poor diet, poor sleep, alcoholism, too many stimulants like caffeine, social isolation, a lack of exercise, or irregular daily rhythms) is a root cause of disease (e.g., the metabolic syndrome afflicting our country). As such, they advocate for lifestyle practices that counteract these HPA axis-disrupting factors, and in many cases significant health benefits follow the adoption of those practices.

Corticosteroids

The hormone cortisol belongs to a class of steroids known as corticosteroids due to its release by the cortex of the adrenal glands. While many related corticosteroids (henceforth referred to as “steroids”) exist within the body, the body’s primary ones are cortisol (a glucocorticoid) and aldosterone, a mineralocorticoid that regulates blood pressure, volume, and electrolyte balance.

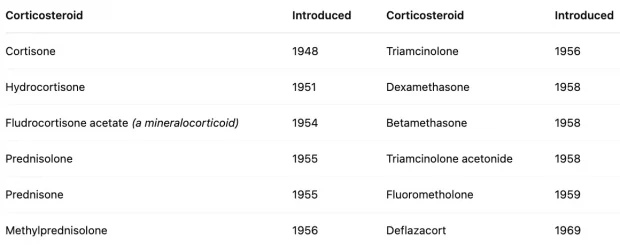

In 1946, the first synthetic steroid (cortisone) was synthesized. Two years later, enough had been produced to test on it a human, where it was discovered to improve rheumatoid arthritis symptoms (which won the 1950 Nobel Prize) and was immediately hailed as a ‘wonder drug.’ Before long, it was discovered that other inflammatory syndromes also responded to cortisone, and a rush of other steroids hit the market:

Following its success in rheumatoid arthritis, steroids (e.g., prednisone, hydrocortisone) were rapidly adopted for a wide range of inflammatory and autoimmune disorders, including systemic lupus erythematosus, inflammatory bowel disease, and multiple sclerosis, due to their ability to suppress immune-mediated tissue damage.

In the early 1950s, steroids were hailed as a revolutionary treatment for those conditions (and hence widely prescribed), with new steroids (e.g., prednisone) being rapidly introduced to the market, but in the late 1950s, serious side effects began to accumulate from long-term steroid use. By the early 1960s, steroid treatment was ‘‘shunned altogether by the rheumatology community” (to the point shortly after that NSAIDs like ibuprofen were named non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to distinguish them from the disastrous steroids) after which point steroids were prescribed with more caution and at lower doses until it was reborn in the 1980s under a low dose regimen.

Currently, steroids remain widely used, and their use has gradually increased. For example, in 2009, 6.4% of American adults had used oral steroids at least once in the last year, whereas in 2018, 7.7% did, while a 2017 study found 21.4% of adults (age 18-64) had used at least one oral steroid prescription in the last three years.

Note: after harms were discovered with steroids, a pivot was made that they are safe if “low doses” are given. However, over the decades, what constituted a safe “low dose” has greatly declined (i.e., doses now considered toxic previously were routinely prescribed), and that drop will likely continue to (e.g., in 2016, Europe’s Rheumatology group concluded in was unsafe to give more than 5mg a day of long-term steroids—a figure significantly lower than the current amounts used in America).

Steroid Side Effects

As you would expect, the side effects from taking steroids mirror those seen with excessive cortisol, although in many cases are much more severe.

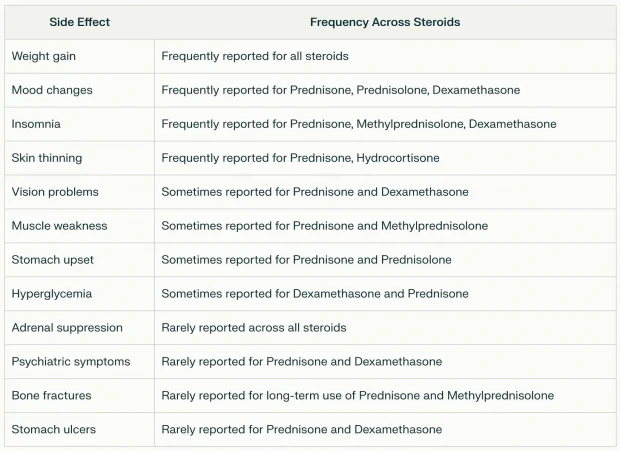

Furthermore, they are quite common (e.g., one study found 90% of users report adverse effects, and 55% report at least one that is very bothersome). Consider this summary of what users across the internet have reported:

Likewise, much of that has been established within the scientific literature:

Bone Loss: Corticosteroids double one’s risk of a fracture (and even more so for a vertebra), with 12% of users reporting fractures. At typical doses, steroids cause a 5-15% loss of bone each year, and in long-term users, 37% experience vertebral fractures (additionally, high dose steroid use increases the risk of vertebral fractures fivefold). Steroid bone loss in fact, is such a common problem that treating it is one of the few official indications the FDA provides for bisphosphonates (which while widely prescribed for bone loss have many severe side effects—including making your bones more likely to break). Lastly, higher doses increase the likelihood of avascular necrosis (with 6.7% of users taking higher steroid doses developing it).

Weight Gain: approximately 70% of individuals taking oral corticosteroids long-term (over 60 days) report weight gain. One study found a 5.73–12.79 lb increase per year, and another found a 4-8% increase in body weight after two years of steroid use. Additionally, this fat typically stores in areas like the face, neck, and belly.

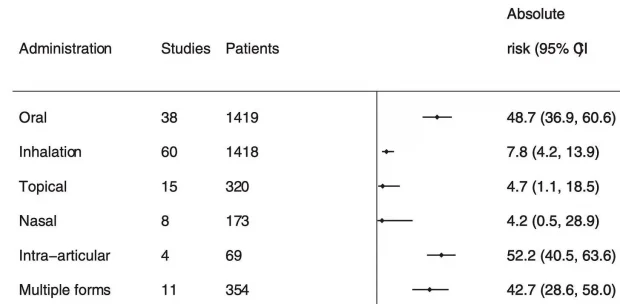

Adrenal Insufficiency: corticosteroids reduce the adrenal gland’s ability to produce cortisol (which can sometimes be life threatening). This is a huge problem that increases with the duration of therapy and systemic routes of administration (e.g., affecting 48.7% of oral users).

Diabetes: a systematic review found individuals taking systemic corticosteroids were 2.6 times more likely to develop hyperglycemia (with 1.8% of those receiving steroids in a hospital then developing diabetes). Likewise, patients who’d taken systemic corticosteroids at least once were 1.85 times more likely to develop diabetes. Finally, a meta-analysis found that, in patients without pre-existing diabetes, a month or more of steroids caused hyperglycemia in 32% and diabetes mellitus in 19% of them.

Cardiovascular: high doses of steroids have been observed to increase heart attacks by 226%, heart failure by 272%, and strokes by 73%.

Eyes: Steroids have been found to increase the risk of cataracts by 245-311% (with 15% of users reporting this side effect) and the risk of ocular hypertension or open angle glaucoma by 41%.

Gastrointestinal: Steroids are linked to many gastrointestinal events (e.g., nausea and vomiting) and have been found to increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding or perforation by 40%.

Psychiatric: between 1.3%-18.4% of steroid users develop psychiatric reactions (with the rates increasing with the dose), and around 5.7% experience severe reactions. Additionally, 61% of steroid users reported sleep disturbances, and steroids can also sometimes cause psychosis.1,2

Infections: Steroids also increase the risk of infections. For example, users of inhaled steroids were found to be 20% more likely to develop tuberculosis, and this increased at higher doses in patients with asthma or COPD. Similarly, patients on steroids were 20% more likely to develop sepsis (possibly due to the initial symptoms of the infection being masked by the steroids).

Skin: prolonged topical use of steroids also frequently causes skin issues (e.g., up to 5% experience skin atrophy after a year of use).

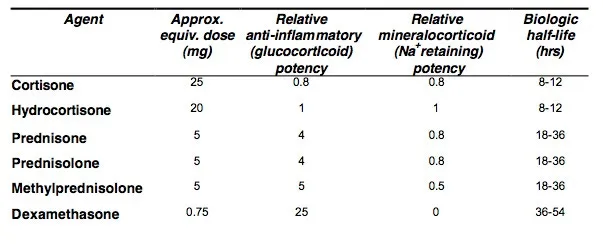

Lastly, certain steroids are much more potent than others, and the more potent ones that persist in the body (e.g., dexamethasone) are more likely to create systemic effects like HPA axis dysfunction.

Uses of Steroids

The toxicity of steroids greatly increases with prolonged doses and routes of administration that have systemic absorption (e.g., oral). Because of this, many now believe they should be reserved for life-threatening emergencies (with the side effects that frequently follow being an acceptable trade off) and for a prolonged period, only be used in a manner with minimal systemic absorption (e.g., topically).

Note: I recently interviewed a variety of specialists for their perspectives on using steroids in their fields of medicine. Collectively, they felt that while steroids can be helpful, they are frequently prescribed in an inappropriate manner that causes more harm than good (discussed here).

Chair Yoga for Weight ...

Best Price: $16.47

Buy New $16.97

(as of 03:06 UTC - Details)

Chair Yoga for Weight ...

Best Price: $16.47

Buy New $16.97

(as of 03:06 UTC - Details)

Inhaled Steroids

Inhaled steroids are routinely used to treat asthma and COPD. Since the systemic absorption of inhaled steroids is much less than from oral steroids, systemic side effects are rarer (but can still occur with prolonged use at higher doses).

While inhaled steroids (along with the other medications commonly prescribed for these respiratory conditions) can help and are often the only option available to patients, I believe in most cases natural therapies that directly treat the conditions are preferable. For example, COPD is seen as a progressive and incurable illness which can only be delayed or partially mitigated with the existing therapies. In contrast, when nebulized glutathione is used to replenish the protective lining of the lungs, it halts the progression of the disease, and unlike steroids does so without side effects. Likewise, many natural therapies exist for asthma.

Topical Steroids

Topical steroids are routinely used for skin issues and sometimes in other areas as well, such as for certain eye conditions, like preventing graft rejection after a necessary corneal transplant. In these instances, systemic side effects are rare, and most local issues result from prolonged use (e.g., skin changes or skin thinning—particularly on the face).

Note: I have long suspected topical steroids in part work by reducing fluid circulation to the skin (via the insterstitium), thereby preventing inflammatory toxins from arriving there and creating skin reactions (whereas agents like DMSO treat skin conditions by augmenting the skin’s microcirculation so stagnant toxins cannot irritate a set area). As such, due to the potential issues with suppressing skin symptoms, I typically treat skin issues with natural therapies like DMSO or by eliminating the underlying cause of the skin issue.