On Israel, the Palestinian Territories and the Doubtful Project of Liberal Peacemaking

A Plague Chronicle

October 13, 2023

I’ve had a bit of self-imposed writer’s block recently. There are things I want to say about the discourse around the Hamas attacks and the Israeli response that are very delicate and which, I fear, will earn me few friends. So, until this morning, I’ve tried very hard not to write them. I’ve now given up on that plan – after all, there’s little point in running an anonymous blog if you can’t say what you think. Before you get angry, note that I am only trying to speak of things as they are, and not as I want them to be. I’ve written this as neutrally as I can.

Most of us live inside liberal (or, increasingly, post-liberal) political systems, and especially since 1990 there is no unified, credible alternative in sight. In consequence, it becomes easy to mistake many contingent ideological constructs for moral principles universal to all of humanity, or even for features of reality. A cluster of these constructs attach to that universal human activity we call war.

Liberalism at least claims to have a deep distaste for war. It has called into being an entire international system of diplomacy and peacekeeping to head off armed hostilities and stop them once they have started. It deplores aggressors and aims to impose an international criminal code on the activities of belligerents, which is designed above all to spare civilian populations and confine armed conflict to soldiers and military infrastructure. Whenever a conflict breaks out, we have long arguments about which party is the aggressor, which party is entitled to defence, which attacks by which party might be justified or excessive, and what kind of peaceful solutions we can impose.

However strange it may be to contemplate, ancient peoples and even many today outside the liberal West thought and think about armed conflict much differently. Specifically, the unspoken assumption that there can be stable political alternatives to war in most or even all instances has become an intriguing Western preoccupation, as is the general notion that war is a thing for international institutions to adjudicate and manage away.

The liberal discourse surrounding war also suffers from some telling internal problems of coherence. Perhaps the greatest of these is that liberal states, insofar as they claim to channel the wishes of the people, inevitably implicate these ‘people’ in their aggression, even as they elaborate a legal and moral system premised on shielding civilians. I think much liberal anxiety about war crimes and atrocities arises from this central tension.

Nor can it be said that liberal states never target civilians with measures ranging from sanctions to bombardment; they do so routinely, and there is much to recommend the ‘realist’ thesis that their behaviour hardly differs from that of illiberal nations. If anything, ascendant liberal states may be even more aggressive than we’d otherwise expect. Because they regard the right to self-determination and democracy as the most urgent moral principles, prior to all other politics, liberalism itself can become a casus belli justifying all manner of brutality. The 2003 Iraq War is a shining example.

For these and other reasons, it is hard to see talk of war crimes and human rights violations as the pure expression of a high-minded liberal morality which has civilised itself beyond the point of needing war. On the contrary, this kind of rhetoric often resembles little more than convenient accusations levelled opportunistically at enemies. It helps that liberal norms regarding warfare have a remarkable flexibility which suits them for this purpose. Many of the arguments against the Russian invasion of Ukraine, for example, can be redeployed against the Kiev regime simply by adopting the perspective of the pro-Russian peoples of the Donbas instead. Or, lest you think I am too partisan to be objective in this case, consider an example nearer to (my) home: Now that recession has made Germany desperate as never before for good economic relations with China, EU sanctions for Chinese human rights abuses in Xinjiang have become inconvenient. Thus we are provided long and learned investigations of the Islamic terror campaigns waged by the Uyghurs between 2010 and 2016 and the justified nature of Chinese security concerns in the region.1

While it is totally understandable to oppose death and destruction, I am pessimistic that the liberal order always has good solutions, and I think invoking liberal rhetoric to justify or defend specific parties in a conflict is generally unhelpful. Since this rhetoric can excuse or condemn almost anybody, it frequently tends to do little more than support the interests of dominant liberal powers.

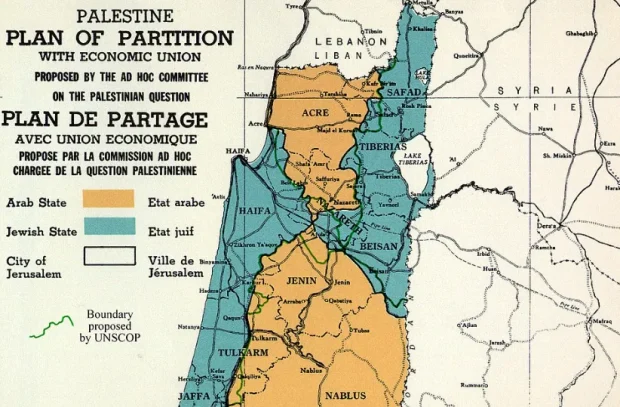

None of this is to say that this liberal rhetoric doesn’t matter. In all those lands subject or peripheral to American liberal hegemony, liberal appeals can be very powerful, even when raised by parties which do not seem especially inclined to liberalism themselves. (The universal nature of liberal claims makes the system entirely open to instrumentalisation of this nature.) The Palestinians and their supporters have used these appeals to defend themselves and confine the options of Israel since at least 1948. In this environment, parties like Hamas even benefit from provoking Israeli retaliation. ‘Terrorism’ is an imprecise term for many things, but an important subset of the activity gathered under this heading appears to exist in complex symbiosis with core liberal attitudes regarding armed conflict.

Copyright © Eugyppius