In this climate of accelerating intolerance for any cultural expression that predates this morning’s ethical pinnacle of woke self-indulgence, Progressive catechisms have never rung more hollow.

The preposterous self-importance that recently witnessed “adults” debating whether or not the vintage holiday song “Baby It’s Cold Outside” constituted an “ode to rape”—and in the very summer that witnessed Amazon pull Gone with the Wind (Selznik, 1939) before Atlanta being unironically burned to the ground by America’s extra-chromosome Left—is it silly to anticipate a comparable cancellation of a far more prominent icon of traditional America, the entire memeplex around the perennial bugaboo, White Christmas?

I won’t rehearse the entire woke antipathy to Irving Berlin’s song, first popularized in Paramount’s Holiday Inn of 1942 and immortalized by Bing Crosby’s homey baritone and moody, scooping diphthongs. It’s entirely possible that only an infinitesimal minority of Americans born between 1885 and 1995 would find themselves unable sing a few bars from memory. As the world’s best-selling single in the age of mechanically reproducible music—until Elton’s John’s 1997 remake of “Candle in the Wind” in honor of the late Princess Di which marked the significant transition to digital reproduction—it was incredibly simple, just fifty-four words and sixty-seven notes. And while there is an interesting backstory to the various recordings in circulation, I was delighted to have my hunch confirmed that the set for Holiday Inn was reused for 1954’s White Christmas (Paramount). Now, the real question I need answered is whether or not it was also used for Christmas in Connecticut (Warner Bros., 1945)!

Ideas Have Consequence...

Best Price: $6.84

Buy New $13.31

(as of 03:40 UTC - Details)

Ideas Have Consequence...

Best Price: $6.84

Buy New $13.31

(as of 03:40 UTC - Details)

The lightning rod for the rebarbative Left is, as always, a semantic issue not an empirical one. In this, one is reminded of Richard Weaver’s argument about the tragedy of the nominalist take-over of post-medieval culture in Ideas Have Consequences (1948). That words can trigger the psychologically frail reminds us of the sturdy folk wisdom we all grew up with, “sticks and stones…” The absence of this simple lesson alone probably accounts for more psychiatric prescriptions in this century than any other fact of life. Today, “silence is violence,” but violence is… well, it’s censored unless it fits “the Narrative.”

“White.” Do we need to go any further? And “Christmas?”

I mean, really, can there be another three syllables that so elegantly compress the entire Christo-fascist program into one hard gemstone of pure, lustrous hatred?

While it is not difficult to design experiments to reveal the reasoning processes of lab animals and house pets, this is not the case for Progressives and socialists. In the animal kingdom at least, these efforts are largely successful because the structure of inferential logic circuits in the cortices of most mammals exhibit a stable anatomical structure and clearly differentiated, if nested, functional operations that are repeatable and reproducible. This is not the case for human beings who have had these logic circuits “recoded” by emotional noise, deactivating both simple calculation as well as higher forms of disinterested reason. The “recoding” is indoctrination; the “emotional noise” is the learned magnification of affective inputs.

What goes under the rubric of “education” in the United States is actually a form of intentional distortion of our innate capacity for empathy and detached, deliberative ratiocination. Students acquire this intentional disability in order to consider themselves educated. It’s a sick and twisted tale that goes back to the creation of the Prussian educational system in the wake of the humiliation wrought by Napoleon’s swift subjugation, and Horace Mann’s importation of this system to our country in the 1840s.

Missing from this emotion-drenched approach to the world and human culture is the capacity to grasp actual, shared historical facts. Anything that informs the mindset behind the creation of any artifact, especially one that strikes a chord with millions of people across three or four generations, is regarded as counterproductive to raised consciousness.

White Christmas (Blu-r...

Best Price: $6.43

Buy New $11.99

(as of 06:55 UTC - Details)

White Christmas (Blu-r...

Best Price: $6.43

Buy New $11.99

(as of 06:55 UTC - Details)

While this isn’t the place for a fully-developed, sympathetic analysis of the symbolism of the entire “White Christmas” phenomena—from the 1942 single, its recording in Holiday Inn, and its regeneration in the blockbuster film—I think one can make reasonable statements about the lyrics, the script, and the 1954 staging that would probably align with the tacit assumptions and values of the national audience from this period (1942-1954).

The rough prototype for my analysis is Stefan Zweig’s autobiographical epiphany that he had lived in three worlds: the world prior to the Great War, the world that followed in its wake, and the emergence of modern barbarisms of national and international socialism that prepared the second global conflagration of his lifetime. His tragic suicide was his decision to avoid that third world, and the fourth world it would create.

My belief is that White Christmas does not simply invoke nostalgia for one’s youth and the rose-colored memories of long-lost relatives celebrating the birth of our Savior. The film is actually a testimony to the good-natured resilience of the pre-Great War world where the values of humility, honesty, hard work, and thrift were not lifestyle choices but survival strategies. Like Remember the Night (Paramount, 1940)—another Christmas classic from Hollywood’s golden age—the values of the protagonists’ parents were pitted against their own pressing, personal appetites and the relentless, anonymous social forces of the situation in which they found themselves, in that case the justice system. In both cases, the wisdom of the parents’ generation wins out. And White Christmas is a hymn to that victory.

I think the first safe assumption is that White Christmas’ chronological “meridian,” if you will, might be the year 1903, the year of Crosby’s birth. Crosby, whose voice provides the physical embodiment of the sentiments and affections evoked in the lyrics and score, would have had his deepest and most profound formative childhood experiences prior to his adolescence and the transformation of the country and the world in the events of World War One. Zweig has a memorable passage describing how in 1941, when visitors to the cinema are shown men and women from the year 1900, they “break out into uncontrolled laughter.” The norms of Zweig’s entitled youth had become “historical and incomprehensible” to the next generation, and that became the filter for Berlin, for Crosby, and for director Michael Curtiz (1886-1962).

This was a world before automobiles were even a novelty in most parts of the country and a world where few people had indoor plumbing, to say nothing of electrical service. There were only forty-five states at the time and the chances are that your grandparents’ generation had a few Civil War veterans on one side or the other. When Crosby was a small boy, if his parents wanted coffee they first had to make a fire; and when anything was delivered, it was probably taken off a horse-drawn wagon.

It’s a Wonderful...

Best Price: $8.01

Buy New $7.40

(as of 06:55 UTC - Details)

It’s a Wonderful...

Best Price: $8.01

Buy New $7.40

(as of 06:55 UTC - Details)

He and his cohort would have not had vivid memories of the Great War beyond echoes in popular culture. The dark theaters where silent films replaced the wholesome analog experience of Vaudeville was making “entertainment” into a mass commodity. Cars, phones, and radios went from being luxuries to being ubiquitous commodities during the 1920s.

All of this cultural, economic, and technological churn came to be the norm: standing still amidst all the change became the balancing act that enabled his generation to adapt first to roadways without paving, let alone traffic lights, and to the enormous wealth accumulation which would certainly have concerned their elders. These themes form the plotlines of several Hollywood productions. Make Way for Tomorrow (Paramount, 1937) is a wrenching exploration of the intergenerational moral friction between nineteenth-century parents and their twentieth-century offspring that, in many ways, offers a handy reference to twentieth-century parents and their twenty-first-century children. White Christmas filters these frictions through the lenses of loyalty and patriotism. The forms of expression may be novel, but we see though them an allegiance to the sources of pre-modern inspiration.

And unlike the Austrian belle-lettrist Zweig, with his “livid steeds of the Apocalypse,” Americans were quick to salvage what we could from the past, pragmatically repurposing it for artistic inspiration. Entire production numbers leverage our useable past, and make it a springboard into contemporary expression—“Choreography” mocks modern European abstract dancing in favor of good ol’ fashion, on-stage hoofing; “Minstrel Show” is a post-blackface homage to the artistry of African American folk music and the roots of jazz. With the exception of the seductive “Mandy,” most all of the numbers rely on stock American pop culture topoi to make a connection to the audience. The working assumption is that we all share a broad river of cultural expression, we all add to it, and Hollywood is one funnel through which it is fed back out for refiltration, with new twists here and there but with an intact moral core.

Indeed the script of White Christmas, and the other holiday classics from this generation, holds fast to the moral wisdom of its elders’ generations. We did not twice host the scorched earth of post-war Europe and can be excused for seeing our past with less anger. In the 1950s, as Europe was rebuilding according to the moral strictures of Le Corbusier and the Bauhaus, we were building split-level neo-colonials and driving pink convertibles.

We were PoMo before we were Mo!

Miracle On 34th St (bw)

Best Price: $8.01

Buy New $6.99

(as of 06:55 UTC - Details)

And beyond the white, look afresh at the lurid, saturated colors of White Christmas. Reds and greens so deep and resonant that they buzz on your optic nerve as you follow the contour of the holly leaves in the opening credits. The Argentinian blue of the “Sisters” and their costumes, the hemoglobin red of the linens in “Minstrel,” and the shocking pinks and hot yellows of other costumes, to say nothing of the warm, creamy flesh tones of the interiors. There is more chromatic excitement in this movie than in anything prior to the time-travel sequence in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (MGM, 1968).

Miracle On 34th St (bw)

Best Price: $8.01

Buy New $6.99

(as of 06:55 UTC - Details)

And beyond the white, look afresh at the lurid, saturated colors of White Christmas. Reds and greens so deep and resonant that they buzz on your optic nerve as you follow the contour of the holly leaves in the opening credits. The Argentinian blue of the “Sisters” and their costumes, the hemoglobin red of the linens in “Minstrel,” and the shocking pinks and hot yellows of other costumes, to say nothing of the warm, creamy flesh tones of the interiors. There is more chromatic excitement in this movie than in anything prior to the time-travel sequence in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (MGM, 1968).

If anything, the whiteness of White Christmas is a luminous and available source of moral energy, a light beam from a distant star. Whereas the regressive Left chose to see our “great enrichment” during the Industrial Revolution as the source of human misery, we chose to see it as it was : the antidote to a miserable, impoverished, short life stranded on a distant farm with limited capital and even less access to opportunity. With the exception of “Mandy’s” white leotard, whiteness throughout is about purity and moral excellence. Crosby’s character was a “knight on a white steed” until he is wrongly assumed to be cutting a deal; then he’s restored, in the final moments of the film, to his place.

The whiteness of White Christmas is the symbolic purity of a world energy uncorrupted by socialism, by world war, mass death, famine, genocide, fiat money, forced labor, and conscription. It was a world in which people daily toiled, adjusted their lives to the output of that toil, and understood the moral balance within would be reckoned with the balance without, regardless of one’s faith. The microcosm and macrocosm that undergirds every Mosaic faith is the subtext. And that faith in the once-good and the Eternal Good is the core that makes us well up with tears as we watch and contemplate how such people faced tectonic change, constant upheaval, and industrial-grade inhumanity—and could go ahead and make these silly stories!

One of the great losses we have suffered in the corrosive onslaught of our American culture by the Cultural Marxists, the Progressives, and today’s cognitively and morally impaired Left is the outright destruction of middle-brow culture.

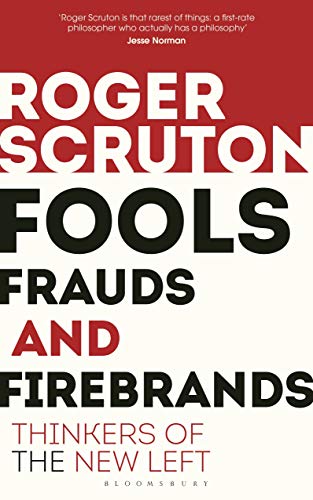

American middle-brow taste offered access to the imagery and energy of high culture without the time and the mental demands; as a trade-off, it conveyed a thumbnail sketch of the enduring themes of high-brow culture, of permanence, continuity, and moral comfort. But this was seen by warlocks of the Frankfurt School as Kitsch, as non- or sub-art and unworthy of an adult. I think one of the things we see today, in the wake of 2016 and 2020, is that there are tens of millions of people who want that access to those noble themes even though they may simply not have the time or bandwidth for the full message. And thanks to the “frauds and firebrands” described by the late Roger Scruton, we have done away with middle-brow culture altogether. Because high-brow culture will not scale, we are left with efforts that constantly refresh the low-brow with ever lower, more depraved sources of human experience. We are denied Schlock because it is Kitsch, but are forced to ingest filth in its stead.

Fools, Frauds and Fire...

Best Price: $15.32

Buy New $17.40

(as of 03:56 UTC - Details)

Fools, Frauds and Fire...

Best Price: $15.32

Buy New $17.40

(as of 03:56 UTC - Details)

If there is a silver lining to a whiteness theme, it is that the whiteness of White Christmas—the glow of pure motives, loving families, of true hope in the payoff of genuine effort—is something that can be shared by everyone willing to put in the time and the effort.

And if anything else has been made clear in the last four years, it is up to us to demand and to supply the culture we deserve.

Originally published on Letters From Fly Over Country.