In my book Who REALLY Killed Martin Luther King Jr.?, I detailed not only William Bradford Huie’s central role in framing James Earl Ray as MLK’s assassin but noted a number of earlier instances of his long-term association with J. Edgar Hoover, dating back to the 1940s. The story about Huie’s involvement with Hoover and the FBI in the aftermath of the murder of three young civil rights workers had not been addressed. To fill that void, this story adds substance and context to their association, which inexorably led to greater closeness between them, thus creating the kind of trust that would be required for his key covert mission — one of ensuring that Huie’s myth would immediately be inserted into the public consciousness.

On June 21, 1964 three civil rights workers were murdered near Philadelphia, MS. The FBI and two hundred Navy sailors searched for the bodies but failed to find them. According to Wikipedia, “The three men’s bodies were only discovered two months later thanks to a tip-off.” What Wikipedia left off of that description was that the “tip-off” was from one of the culprits, who they paid $30,000 ($244,000 today) for the information — a technique taught to them by the unscrupulous author William Bradford Huie. This was not the first, nor the last, time that the FBI would work closely with Huie in their long association. Four years later, the FBI gave Huie a new, highly secret covert mission to “frame” James Earl Ray for the murder of Martin Luther King Jr.

In late July, Huie contacted the FBI’s Special Agent in Charge (SAC) in Jackson, Mississippi where he fielded the idea of his possible intervention into the search, broaching the suggestion that he offer one of the suspects $25,000 for information regarding the location of the bodies. He explained that he had already been given a $5,000 advance for an article to be written for the Saturday Evening Post regarding the murders. [1]

Three months later, Huie reappeared in the Jackson FBI field office, having published his story in the Saturday Evening Post about the murders. He announced that he had been given a $40,000 advance for a book to be published by Christmas, first in newspaper serial form, then “a cheap paperback edition” followed by a hardback “to be published later by Doubleday.” Though it is stated very subtlety in the Jackson SAC’s report to FBI headquarters dated 10/20/64, it is clear that the FBI acknowledged to him (but not publicly) that they had paid one of the murderers for the information about the location of the bodies:

The comments of the Jackson Special Agent in Charge (SAC) reveal his own insights about the “fiction writer” Huie who liked, occasionally, to be factually correct, but preferred not to get too hung up on that because in books he could “take more license” than normal reporters and magazine writers. It appears that his purpose that day had more to do with gaining an acknowledgement that the idea he had planted three months previously had taken root and it had indeed been the device that produced the bodies; it was as if he needed the recognition and affirmation that resorting to his scurrilous methods was indeed worth the price.

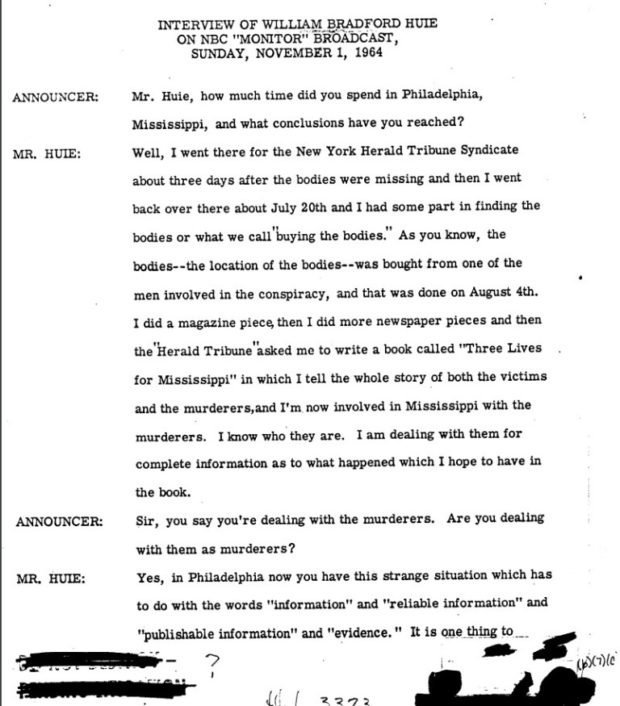

Twelve days later, on Sunday, November 1st, he went to an interview on NBC’s “Monitor” television show. It wasn’t enough for him that he got the nod from the Jackson SAC that they had adopted his idea for the payoff; evidently, to feed his own hubris and nourish his inflated ego, he decided that he couldn’t hold the secret anymore and needed the entire nation’s praise for “solving” the case through the short-cut that he had championed, as he then deliberately leaked the FBI’s secret when he let it slip that he had a key role in solving the triple-murder case:

Huie noted the ironies that his methods created, as he explained his plan for paying the murderer another $10,000 (over $83,000 in today’s currency) despite the fact that the state had not filed charges against any of them at that point. He even noted the question of the “morality” of paying murderers for information, knowing that the local citizenry would close ranks around the accused men to ensure they would not be terribly inconvenienced:

It took three years for the federal government to finally charge 18 individuals with civil rights violations (In his memoirs, William Sullivan stated that there were 19 Klansmen involved, which might have meant that, in addition to his windfall in cash, the informer received a pass on his participation). Seven were convicted and received relatively minor sentences for their actions. The state of Mississippi decided to let the murder charges go for the next forty (40) years, before finally charging one of the murderers, Edgar Ray Killen, with three counts of manslaughter. He was convicted in 2005 and sentenced to 60 years in prison, but only served a little over 12 years before dying in prison of old age.

Who REALLY Killed Mart...

Best Price: $4.76

Buy New $11.23

(as of 12:55 UTC - Details)

Who REALLY Killed Mart...

Best Price: $4.76

Buy New $11.23

(as of 12:55 UTC - Details)

Though William Bradford Huie had a long-term, very productive relationship with the most Machiavellian FBI officials of the 20th century, others, with no axes to grind or fortunes to pay to him, did not think much of the unctuous “fiction writer” from Hartselle, Alabama. One such person, Louise Hermey Stanford, had worked in the Meridian, Mississippi office of the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) in the summer of 1964 and had been the first to report the disappearance of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner; she was involved in the search for the men, visiting the burned church where the men were going the day they disappeared and identifying the burned automobile the men had been driving that day. Ms. Stanford was interviewed by Sibyl Jackson from the LBJ Library in September, 1989 for an oral history. The excerpts below reference the matter of the existence of a paid informant — though not “secret” anymore, effectively concealed from most books, articles and official documents (Exhibit “A” is the Wikipedia site referenced above):

- SJ: “Was there any speculation as to whom the informant had been that tipped the FBI off to the location of the bodies?

- LHS: “No, I heard nothing about that. I read William Bradford Huie’s book [Three Lives for Mississippi] several years later and found out that there was an informant. I don’t know if it was the informant that he was talking about. I don’t trust anything that he wrote from encounters with the man, but I was not aware that summer that there was an informant or if I heard it, it didn’t make much difference.” [Emphasis added].

- SJ: “Right. It’s on record that the FBI could have possibly paid as much as thirty thousand dollars and that the informants led them to the bodies.”

- LHS: ” That’s what I have read and heard that the reward was thirty thousand dollars. I never heard any speculation as to who it might have been or that it was male, female, or whatever. I just never heard anything about it.”

A cousin of Ms. Hermey Stanford, Judith Haemmerle, added a description of one of those “encounters” in her one-star Amazon review of Huie’s book, about how Hermey had thrown him out of the COFO office as the following excerpts from that review illustrate:

- Before her stint ended at the COFO office in Meridian in the summer of 1964, Hermey said she briefly spoke to one journalist, William Bradford Huie, author of the 1965 book, Three Lives for Mississippi. “He hung around the (COFO) office,” she said. “I caught him making long-distance calls and kicked him out of the office.

- As he walked away, he said, ‘You’ll be sorry for this. I’ll write you out of history.’ Her name never appeared in Huie’s book.”

- Ms. Haemmerle’s final lament: I’m wary of journalists who have personal agendas, especially spiteful ones.

William C. Sullivan, in his memoirs published after his mysterious 1977 death (shortly before he was scheduled to testify to the House Select Committee on Assassinations) caused by a hunter who mistook him for a deer, stated:[3]

- “The bureau probably saved taxpayers hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of investigating hours by paying our informant thirty thousand. Without informants, any police department — federal, state, or local — would be almost helpless” [as if the issue were merely one of the use of “informants”, ignoring the 800 lb. elephant in the room, that this “informant” was one of the murderers].

- “But they were apprehended and President Johnson was off the hook.”

It will never be known how the triple-murder of the civil rights workers might have turned out if the FBI had stuck with more conventional methods. What is known is that one of the 19 men — who, together, ambushed the idealistic young men who must have realized how dangerous their mission was — profited greatly from what amounted to a bribe.

And we know that William Bradford Huie greatly profited, not only for the payments for his magazine articles and two editions of his book, but how he had saved himself the cost of bribing the man willing to sell out his eighteen KKK “friends”. It is not clear from the Weisberg files whether he ever paid the man an additional $10,000 for further information for his book, as he explained in his NBC interview.

Finally, we also know that Huie, the famed “checkbook journalist” who had ingratiated himself into a number of unsavory missions for his own financial and promotional benefit, was an unprincipled, unscrupulous and mendacious man willing to do anything for financial rewards and public accolades. He proved that four years after this event when he accepted a new mission from FBI HQ: The mission to frame James Earl Ray, as described at length in Who REALLY Killed Martin Luther King Jr.?

ENDNOTES

[1] See Harold Weisberg Collection, Hood College, Frederick, MD: http://jfk.hood.edu/Collection/Weisberg%20Subject%20Index%20Files/H%20Disk/Huie%20William%20Bradford/Item%2056.pdf

[2] LBJ Library Oral Histories, LBJ Presidential Library, accessed 9/25/2019: Oral history transcript, Louise Hermey Stanford, interview 1 (I), 9/6/1989, by Sybil Jackson ( https://www.discoverlbj.org/item/oh-stanfordl-19890906-1-06-19 )

[3] Sullivan, William C., The Bureau: My Thirty Years in Hoover’s FBI, W.W. Norton & Company, New York, 1979, p. 77