None knew it then, but in 1915, Southern agrarian influence on the movies was at its height. The film trade had just left Fort Lee, New Jersey, only to land in the equally piously named Mount Lee, California. Of course, the latter’s new name was Hollywood, due to its Kansas prohibitionist developers, but it was also the same name as the Richmond cemetery sanctified by so many Confederate figures.

More important was that the industry leader was director David Wark Griffith, son of a Kentucky Confederate colonel and the man who dominated the industry almost from the moment he started making shorts for Biograph. All that was really pre-history. On February 8, he premiered The Birth of a Nation at Clune’s Auditorium. This Southern view of the Confederacy and Reconstruction is the most important movie in history. It became the biggest hit ever and provided the cash for innumerable film fortunes. Politics aside, no film historian disagrees that it’s the most important film artistically in that it served as the textbook for generations of filmmakers.

The South Was Right!

Best Price: $21.38

Buy New $36.15

(as of 10:45 UTC - Details)

Griffith reluctantly entered movies as an actor when his stage career stalled. Soon, he was directing one or two shorts a week for Biograph, Thomas Edison’s studio. Other companies may have had a plusher, more streamlined look, but Griffith’s work had passion which others took for ingenuity and studied. It is routinely claimed that he invented the close-up or the dissolve or cross cutting between scenes. He didn’t. He just did them better, not because he had a better crew, but because he had a better eye and sense of values to back up his dramatic mind. He didn’t just titillate you, but made you care for his characters more than anyone else did.

The South Was Right!

Best Price: $21.38

Buy New $36.15

(as of 10:45 UTC - Details)

Griffith reluctantly entered movies as an actor when his stage career stalled. Soon, he was directing one or two shorts a week for Biograph, Thomas Edison’s studio. Other companies may have had a plusher, more streamlined look, but Griffith’s work had passion which others took for ingenuity and studied. It is routinely claimed that he invented the close-up or the dissolve or cross cutting between scenes. He didn’t. He just did them better, not because he had a better crew, but because he had a better eye and sense of values to back up his dramatic mind. He didn’t just titillate you, but made you care for his characters more than anyone else did.

By the time he did The Birth, he had shot eleven Confederacy theme shorts, plus one anti-Klan picture, The Rose of Kentucky. In 1914, he was set up in the old Kinemacolor studio around the intersection of Hollywood and Sunset Boulevards. A Confederate project was his dream, but the immediate impetus seems to have been an associate who had worked with Kinemacolor on an ill-fated earlier attempt to bring Thomas Dixon’s play The Clansman to the screen in color. (The idea had been to follow a traveling company around and shoot it between performances.) Griffith knew the play since his first wife had done it.

He bought it and the source novel from Dixon, plus another book The Leopard’s Spots, and added stories he had heard from his father.

His tale has the Stoneman brothers and their sister Elsie (Lillian Gish) planning to visit their old friends the Cameron boys in South Carolina as the war breaks out. Ben, the Little Colonel (Henry B. Walthall), falls in love with Elsie from just her photo. At Petersburg, a wounded Ben leads a final, desperate charge to a cannon and rams a Confederate flag staff in it. The Yankees recognize his bravery and let him through. He recovers in a prison hospital where he finally meets Elsie. The first half ends with the two remaining young Stonemans witnesses of Lincoln’s assassination.

After the war, Elsie and her brother arrive in Piedmont, the Cameron hometown, where their father Austin, patterned on Thaddeus Stevens, takes personal charge of Reconstruction in the state. Despite all the atrocities, Elsie and Ben are still in love, as are her brother with his sister. Stoneman promotes Silas Lynch as the leader of his new black power base.

Ben conceives of the Ku Klux Klan to counter Reconstruction just before his younger sister (Mae Marsh) leaps to her death while escaping a black rapist. The rapist is tried and executed by the Klan and deposited on Lynch’s doorstep. The Yankees respond with their black troops. Anarchy breaks out. The Camerons are trapped in the cabin of Union veterans by the troops. The Klan gathers and rescues them in Griffith’s most famous race to the rescue. (Future director John Ford played a Klansman. He fell off his horse and was knocked out. He woke up to see Griffith hovering over him. Although not a true protege as so many others were, he was the director most faithful to Griffith’s spirit for over fifty years, starting with his first feature Straight Shooting. It ends with a rescue that’s almost a shot for shot reworking of this one. Taking a potentially killer fall and waking up to see Griffith standing in for God must have been a religious experience.)

The couples are married and imagine a future in which Mars, the god of war, is supplanted by Jesus in allegorical shots.

Griffith was genuinely amazed at the controversy his view of Reconstruction caused. He made some minor cuts, but they don’t seem to have made any real difference.

Real controversy about a movie was new back then, but this publicity for The Birth was good for only so much initial push. But as a dramatic entity, the film really delivered. Major roadshow reissues continued well into the twenties. Griffith practically remade it as a World War I movie, Hearts of the World.

The controversy has never ended. It was one of the NAACP’s first causes. Even today when it runs, newspapers often receive form letters that have been used for decades.

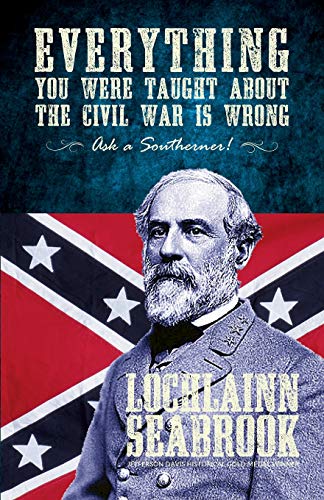

Everything You Were Ta...

Best Price: $16.20

Buy New $14.98

(as of 09:10 UTC - Details)

Everything You Were Ta...

Best Price: $16.20

Buy New $14.98

(as of 09:10 UTC - Details)

The recent British-PBS documentary on Griffith shows this. The British filmmakers finished it with no complaints from their British backers. But then the PBS partners demanded that two black voices be gratuitously inserted.

In 1965, I had some experience with this when I loaned the last reel of my 8mm print to a student group in a deadly dull high school sociology class, sad to say, to use as an example of KKK recruitment tools. The class was informed of its cinematic importance, what I was interested in. Suffice it to say, the class loved it. Initially, I’m afraid, they just saw it as an old, jerky movie, but they were into it cinematically by the end. The teacher hated what I’d done. It wasn’t even my group! She knew its importance beforehand and couldn’t fault it cinematically, but as a school resource, fortunately one she couldn’t control, she told me she would have preferred a member of the Communist Party as a speaker. This was when the legislature in Raleigh was debating the legality of that on state college campuses.

A few years later I showed it to a local, so called film society, dominated by the usual little theater types. I was expecting trouble, but by their unspoken manner I saw they had a grudging respect for it.

This print’s finest moment came in 1974, when it was shown in Winston-Salem at a conservative gathering, and the titles were read by the immortal Mel Bradford. Sad to say, I wasn’t there.

Griffith started to fight back against his critics with an attack on liberal reformers called The Mother and the Law. But as money came in from The Birth, he added the Crucifixion, the Fall of Babylon, and St. Bartholmew’s Day. He cut between these four segments, ending in one incredible race to the rescue that stretched over 4200 years. He called it Intolerance (1916), the most audacious movie in history. It also lost most of his money from The Birth.