The other day, Donald Trump mentioned that Jeb Bush’s brother, George W. Bush, used Eminent Domain (government seizure of private land) in order to build the baseball stadium that helped make his fortune and position him for a political career. Eminent Domain, of course, runs counter to private property values, which are dearly held by many Republican voters.

Fox News asked Jeb about this, “I don’t think eminent domain should be used for private purposes,” the candidate said, looking awkward, as he so often does. “I don’t know what my brother did or not.”

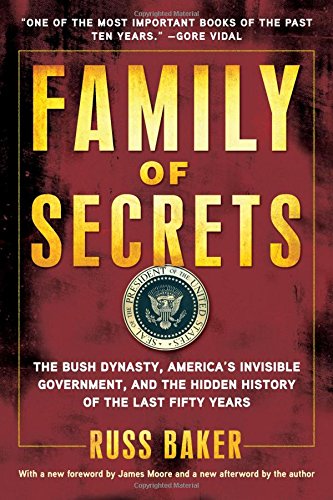

In this case, Trump, who so often blows smoke, was spot on. And since Jeb is unfamiliar with the background, we’ve decided to reprint a chapter in my book on the Bush clan, Family of Secrets, dealing with the baseball team and the land deal.

It’s about the privileges of the sort you and I don’t have.

Feel free to send it along to Jeb.

_________________________________________________________________________

Family of Secrets

Best Price: $1.93

Buy New $8.85

(as of 05:45 UTC - Details)

Here is Chapter 17 of the book Family of Secrets: The Bush Dynasty, America’s Invisible Government and the Hidden History of the Last Fifty Years, by WhoWhatWhy Editor-in-Chief Russ Baker:

Family of Secrets

Best Price: $1.93

Buy New $8.85

(as of 05:45 UTC - Details)

Here is Chapter 17 of the book Family of Secrets: The Bush Dynasty, America’s Invisible Government and the Hidden History of the Last Fifty Years, by WhoWhatWhy Editor-in-Chief Russ Baker:

W. was not quite the baseball player his father and grandfather had been—but he was the master of a certain kind of pitch. In the days leading up to the 1988 election, W. was on the phone constantly making sales calls, though not for his father’s candidacy. As Bush family adviser Doug Wead recalled: “It was interesting to sit and listen to him pick up the phone again and again and say: ‘Well, we’re gonna buy a baseball team. Want to buy a baseball team?’ ”

Maybe George W. Bush felt that his father’s election was in the bag. Or maybe he was in a hurry because he thought it was less unseemly for the son of a vice president seeking the presidency to be soliciting funds for personal reasons than for the son of a sitting president to be doing so. Whatever his reason, at that particular moment, baseball was on his mind.

W. has genuine affection for “America’s pastime,” but his decision to acquire the Texas Rangers baseball team was not just about fun. He was creating a legend that would set him on the path to the presidency. How could a man with so few accomplishments be made into an impressive public figure? How could a fellow who had few prospects of honestly earning a fortune be set up in the sort of lifestyle he and his friends expected?

Such questions were certainly on the mind of his informal political adviser Karl Rove. Although the Bush forces would claim that W. had not seriously thought about running for higher office until well into the 1990s, as far back as Poppy’s inauguration Rove had been letting reporters know that there was another Bush waiting in the wings. In fact, W.’s name was floated as a possibility for the 1990 Texas governor’s race, but W.’s mother publicly opposed his bid because of concerns that a loss would be seen as a referendum on Bush Sr.’s presidency.

Even back then, Rove was envisioning a path for him and his friend straight to the White House. The Texas governorship would give W. a base, and a bucketload of electoral votes to start with. So in the final days before his father’s victory over Democrat Michael Dukakis, George W. Bush was looking toward his own future—first, a brief baseball “baptism” as a public figure, then political office. “Mostly he was talking about his plan with the Rangers and governor, back then,” recalled Wead. “It was Rangers and governor, Rangers, governor, Rangerrrrs . . .”

Anyone seeking a path to the big leagues could do worse than owning a ball team. George W. Bush and his cadre well understood that a winning sports play, like a steady spot in a forward church pew or an art museum with one’s name on it, accorded instant points—and went a long way toward ameliorating deficiencies (particularly moral ones) on other fronts.

The Bushes and their friends had ownership stakes in a lot of teams—the Reds, the Mets, the Tigers, and other favorites. It all started with W.’s greatgrandfather George Herbert “Bert” Walker, who was a force behind professional golf’s Walker Cup and, in fact, the introduction of golf itself into America. He was also a prominent booster of the New York Yacht Club, professional tennis, and premier horse racing. This family legacy culminated in George W. Bush’s successful effort at capturing a new constituency known as the NASCAR voter. Of course, being associated with sports offers obvious benefits in terms of pleasure and ego, but there is little question that the Bush group was adept at leveraging yet one more beloved American institution.

As would be demonstrated by the Supreme Court that would decide the 2000 election in W.’s favor, getting a “fair break” for oneself begins with knowing the referee. Peter Ueberroth, the baseball commissioner at the time W.’s group acquired the Arlington, Texas–based Rangers, was known to be looking for opportunities in politics as he left baseball in 1989, the year Poppy took office. One source close to the negotiations told the New York Times that after W. had failed to persuade the wealthy Texan Richard Rainwater to join the investment group, Ueberroth himself had approached Rainwater and suggested that he team up with Bush, at least partly “out of respect for his father.” As commissioner, Ueberroth was succeeded by Bart Giamatti, an Andover alum who became president of Yale; he was succeeded by Fay Vincent, another old friend of the Bushes who had roughnecked in the oil business in Midland, and even lived at the Bush house briefly when W. was growing up.

W. was relentlessly optimistic about his plans to get into baseball. “He’d get off the phone after somebody said no, and there was not even the slightest disappointment or discouragement,” recalled Doug Wead. “You couldn’t even see a whiff of self-doubt. I thought, man, he’d be a great salesman, he doesn’t even have any [sense of ] rejection.”

Not that there was too much rejection. Smart men—and it was virtually only men who invested—knew that this was a good moment to be in business with George W. Bush, the president’s son.

Family and friends understood the plan: turn a nobody with a famous name into a “somebody,” and, while you’re at it, use the famous name, insider connections, and the implied glamour of the project to make a bundle.

According to Comer Cottrell, a black Republican hair products entrepreneur who put up half a million dollars to become a limited partner, “George brought a lot to the table just by being the president’s son and running for governor . . . Everybody wanted to know him.”

Bush paid six hundred thousand dollars in borrowed money for a 2 percent stake in the Rangers. However, he secured the generous proviso that his share would jump to 11 percent once the partners had gotten their investment out. Thus, the entire deal seemed designed to benefit Bush.