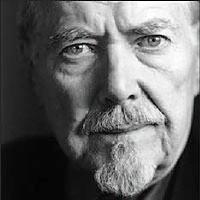

Robert Altman, the director of the movies M.A.S.H. (1970), Nashville (1975), Streamers (1983), The Player (1992), Short Cuts (1993), Prêt -a- Porter (1994) and Gosford Park (2001), amongst many others, is 80 this weekend (February 20th).

Robert Altman, the director of the movies M.A.S.H. (1970), Nashville (1975), Streamers (1983), The Player (1992), Short Cuts (1993), Prêt -a- Porter (1994) and Gosford Park (2001), amongst many others, is 80 this weekend (February 20th).

A lot has been written about Altman and his films, so I do not intend here to do any in-depth analysis. I have no doubt that his movie-making over 40 years has by now been the object of plenty of psychobabble, and countless learned dissertations at Film or Cultural Studies departments in universities throughout the land.

I will simply put my cards on the table. I like Altman’s films, even the bad ones (in parts): unlike much of the fantasy-world fare which regularly tops the charts at the box-office but cannot sustain even a second viewing, they are thought-provoking, funny-melancholic and complex, and repay repeated viewing. Being also intrinsically American, they are especially interesting to one who, like me, is a keenly interested outside observer of 20th-century American culture and history, well-disposed to its founding libertarian traditions.

So I feel it is right and proper today that, having reached the milestone of 80 years, Altman should be fawned over, called yet again the Big Daddy of American art cinema, and have another media moment in the California sun.

He was born on February 20th, 1925 in Kansas City, Missouri, to a Catholic family of German origin.

Freelance writer Stephen Lemons, in an August 2000 article in Salon on the 25th anniversary party for Nashville, describes the adolescent Altman as "a cutup and hell-raiser — to the degree that his parents shipped him off to Wentworth Military Academy in Lexington, Mo., during his junior year of high school." Joining the US Army Air Force from there in 1945, he saw active service at the tail-end of World War II as a bomber pilot in the Pacific.

When he came back he was at a loose end. He tried acting. He tried out a crazy scheme for tagging dogs. He ended up back in Kansas City in 1947 and, at age 22, started out on a life of film by making documentaries for a firm which made industrial shorts, the (now defunct) Calvin Company. From the mid-1950s, after he had written and directed a teen exploitation movie called The Delinquents, he worked in television, first at the invitation of Alfred Hitchcock, on the show "Alfred Hitchcock Presents," and later on several regular TV series, the best-known of which were “Bonanza” and "Combat."

Altman began directing feature-length movies in the 1960s, after leaving TV. But he would not achieve fame until the relatively late age of 45, with the controversially satirical film M.A.S.H., set at the time of the Korean war but clearly intended to refer to Vietnam, which came out in 1970.

"M*A*S*H," as the website of the Directors’ Guild of America tells us on the occasion of a 2003 award to Altman, "featured a sprawling cast of largely unknown actors, so naturalistic that you might assume that they are purely improvising, except that the arching nuances and comic timing hit all too perfectly. Donald Sutherland and Elliott Gould’s characters embody Altman’s split perspective on America, full of anti-authoritarian cynicism and swaggering braggadocio. They are neither the accidental heroes, nor the slow-witted innocents of traditional combat films. They are wise-cracking revolutionaries, smart enough to see through the charade and insanity of war. In general, it is not a fixed disdain for authority that Altman expresses in his films. Instead, he simply combines an outsider’s view with a little wit and lets the absurdity of the establishment reveal itself."

"M*A*S*H," as the website of the Directors’ Guild of America tells us on the occasion of a 2003 award to Altman, "featured a sprawling cast of largely unknown actors, so naturalistic that you might assume that they are purely improvising, except that the arching nuances and comic timing hit all too perfectly. Donald Sutherland and Elliott Gould’s characters embody Altman’s split perspective on America, full of anti-authoritarian cynicism and swaggering braggadocio. They are neither the accidental heroes, nor the slow-witted innocents of traditional combat films. They are wise-cracking revolutionaries, smart enough to see through the charade and insanity of war. In general, it is not a fixed disdain for authority that Altman expresses in his films. Instead, he simply combines an outsider’s view with a little wit and lets the absurdity of the establishment reveal itself."

M.A.S.H. introduced several enduring Altman hallmarks: the lack of linear plot, the unifying theme achieved through a device (in this case the surreal announcements over the field hospital’s PA system), the overlapping dialogue, the director’s paternalism and love-hate relationship with his cast, and the feel of creative, ad-hoc improvisation which can be both so inspiring and so infuriating in all of his films. It also offered up that enduring triple nemesis of modern Puritanism: sex and drugs and rock’n’roll. As Lemons says, it fed audiences "all of the major characteristics of an Altman film: rabid anti-authoritarianism, anti-militarism, black humor (the blackest), sacrilege, delight in decadence, adolescent sexual escapades, hypocrisy revealed and casual drug use."

Altman’s next big success was Nashville (1975). Famously given a rave review in the New Yorker 4 months ahead of its opening by that renowned critic, the late Pauline Kael, for many this film is emblematic of America in the 1970s, maybe even the pinnacle of Altman’s achievement. In the first of two reviews, eminent film critic Roger Ebert wrote:

Altman’s next big success was Nashville (1975). Famously given a rave review in the New Yorker 4 months ahead of its opening by that renowned critic, the late Pauline Kael, for many this film is emblematic of America in the 1970s, maybe even the pinnacle of Altman’s achievement. In the first of two reviews, eminent film critic Roger Ebert wrote:

"Robert Altman’s Nashville, which was the best American movie since Bonnie and Clyde, creates in the relationships of nearly two dozen characters a microcosm of who we were and what we were up to in the 1970s. It’s a film about the losers and the winners, the drifters and the stars in Nashville, and the most complete expression yet of not only the genius but also the humanity of Altman, who sees people with his camera in such a way as to enlarge our own experience. Sure, it’s only a movie. But after I saw it I felt more alive, I felt I understood more about people, I felt somehow wiser. It’s that good a movie. […]

This is a film about America. It deals with our myths, our hungers, our ambitions, and our sense of self. It knows how we talk and how we behave, and it doesn’t flatter us but it does love us."

It is also interesting to note in passing that, even 30 years on, users of the invaluable Internet Movie Database (ImdB) continue to comment in uncommonly large numbers on this movie. One very recent comment makes the point that, "Altman’s slice of Americana has lost none of its punch… Despite being made in the Watergate and Vietnam era…. the film is even more relevant today in this age of celebrity-worship and apathetic, gutless American media who believe missing suburban wives are more pertinent and crucial to this nation’s well-being than questioning facts and our leaders’ motives for waging a needless, costly war."

The next Altman movie on my list is Streamers (1983). Even in the many surveys and articles on Altman available on the Internet, this cinematic adaptation of an intense and close-atmosphered anti-war stage play by David Rabe, set in a basic-training barracks before a group of recruits is sent out to Vietnam, is given little attention, coming from a period in which Altman is regarded as having been generally in the doldrums. It is not available on DVD. Nevertheless, it is as intense an Altman experience as you are ever likely to get, and I strongly recommend it, even if you feel the need for a strong drink afterwards.

The next Altman movie on my list is Streamers (1983). Even in the many surveys and articles on Altman available on the Internet, this cinematic adaptation of an intense and close-atmosphered anti-war stage play by David Rabe, set in a basic-training barracks before a group of recruits is sent out to Vietnam, is given little attention, coming from a period in which Altman is regarded as having been generally in the doldrums. It is not available on DVD. Nevertheless, it is as intense an Altman experience as you are ever likely to get, and I strongly recommend it, even if you feel the need for a strong drink afterwards.

From the IMdB: Streamers is about the truly dramatic consequences of censored communication. It’s a gripping, demanding, powerful and very satisfying film that leaves your head spinning and your heart racing.

It is only fair to mention that there are also strongly negative user comments on this film: one writer calls it a u2018lengthy, lethargic and lackluster Altman lecture.’

This divergence of views highlights the undoubted truth that both Altman the person and his work provoke extreme reactions. It is almost impossible to remain indifferent. As he is loved, so he is also detested: loved by many fans and by the circle of distinguished and well-known actors whom he has regularly allowed to improvise and be themselves in his movies; loved by the professional critics who wax effusive about America having its very own auteur and art cinema director (and yet cannot resist, many of them, the mean pleasure of pulling the man down by gloating over his relative failure at the box-office); detested for his forthright liberal and anti-war opinions by the faux-patriots for whom America can do no wrong, and an object of puzzlement for those who want to go to the movies for nothing too difficult such as actually having to think, but merely to be distracted and carried along by a fanciful and morally simple yarn, preferably involving good guys taking out dark, evil monsters.

Such conflicting reactions were also in evidence in relation to The Player, which came out in 1992 and was hailed at the time as Altman’s u2018comeback.’ This film is oddly unsatisfying and oddly fascinating at the same time, perhaps because it portrays an anti-hero, an unsympathetic and amoral main character who literally gets away with murder, but with whom we nevertheless are drawn to sympathize because he is dealing with the enemy within — within himself and within the vicious, back-stabbing Hollywood milieu, which is portrayed here with a savage bitterness born of intimate familiarity. There is also a strong implicit condemnation of the abject superficiality and pretentiousness of the cult of celebrity, allied with an ironic and paradoxically mischievous delight in it. Like all addictions, you love it and can’t get enough of it, at the same time as you hate what it does to you and want to be rid of it.

Such conflicting reactions were also in evidence in relation to The Player, which came out in 1992 and was hailed at the time as Altman’s u2018comeback.’ This film is oddly unsatisfying and oddly fascinating at the same time, perhaps because it portrays an anti-hero, an unsympathetic and amoral main character who literally gets away with murder, but with whom we nevertheless are drawn to sympathize because he is dealing with the enemy within — within himself and within the vicious, back-stabbing Hollywood milieu, which is portrayed here with a savage bitterness born of intimate familiarity. There is also a strong implicit condemnation of the abject superficiality and pretentiousness of the cult of celebrity, allied with an ironic and paradoxically mischievous delight in it. Like all addictions, you love it and can’t get enough of it, at the same time as you hate what it does to you and want to be rid of it.

Speaking personally, I also find the character played by the usually elegantly attractive actress Greta Scacchi unsympathetic and annoying: she plays a supposedly mysterious and u2018difficult’ artist who is resisting — and yet not resisting — the charms of the anti-hero. It has to be admitted there are times when the deliberate ambiguities and occasional longueurs of an Altman script get to even the keenest of fans.

This movie has the dubious distinction of having attracted the ire of Murray Rothbard, who was disturbed by what he called the nihilism of the u2018New Left’ cinema, which led directors like Altman to show that life is evil and meaningless, rather than to provide happy endings as Old-Left cinema did (Rothbard wished in 1992 that Altman had u2018stayed away forever’). Personally I think Rothbard comes down too hard on Altman, based on this one movie: it is easy to agree with him that what Altman portrays is not a pretty sight. But it is wrong, in my view, to attribute nihilistic intent to the director.

No such reservations apply to the bitter tragi-comedy of manners and life in Los Angeles, Short Cuts (1993), one of my favorite films of all time. It is based on the short stories of the late Raymond Carver (1938—1988), and portrays a set of characters whose lives overlap in strange and unexpected ways. It is a melancholy film, in that its linking theme is the incidence of death, both physical and of the soul, and our common helplessness in the face of it. "The most representative plot," writes Doug Thomas in the editorial review on Amazon.com, "deals with a group of friends (Buck Henry, Fred Ward, and Huey Lewis) who decide to keep fishing even after discovering a body in the river. The story works as a morose comedy and a flag holder for the movie: the inability to take the correct action. […] A huge and talented cast twists in the wind, bumping into moments of truth, sex, and passion. Some even come out all right in the end. The accidental nature of life — a common theme in many Altman films — has never been so maddeningly persistent, or absorbing. The score by Mark Isham, with songs sung by Annie Ross (also a cast member), fuels the moodiness, as does the opening number in which Medfly helicopters spray the town to the tune “Prisoner of Life.”"

No such reservations apply to the bitter tragi-comedy of manners and life in Los Angeles, Short Cuts (1993), one of my favorite films of all time. It is based on the short stories of the late Raymond Carver (1938—1988), and portrays a set of characters whose lives overlap in strange and unexpected ways. It is a melancholy film, in that its linking theme is the incidence of death, both physical and of the soul, and our common helplessness in the face of it. "The most representative plot," writes Doug Thomas in the editorial review on Amazon.com, "deals with a group of friends (Buck Henry, Fred Ward, and Huey Lewis) who decide to keep fishing even after discovering a body in the river. The story works as a morose comedy and a flag holder for the movie: the inability to take the correct action. […] A huge and talented cast twists in the wind, bumping into moments of truth, sex, and passion. Some even come out all right in the end. The accidental nature of life — a common theme in many Altman films — has never been so maddeningly persistent, or absorbing. The score by Mark Isham, with songs sung by Annie Ross (also a cast member), fuels the moodiness, as does the opening number in which Medfly helicopters spray the town to the tune “Prisoner of Life.”"

Short Cuts, at 3 hours longer than usual even for Altman, could be the object of a review unto itself. I will limit myself to saying that this in particular is a film which repays concentration and revisiting: the first time around, you are likely to miss a lot, on account of the wealth of detail, the initial confusion of the overlapping stories and coincidences, and indeed moments of irritation, embarrassment or intense personal drama, as in the argument about marital infidelity between the characters played by Matthew Modine and (a nude) Julianne Moore.

1994’s Prêt -A- Porter (Ready to Wear) was slammed by many critics, and once again, viewer opinion is harshly divided. The film, which is a shaggy-dog story, actually contains some delicious moments (particularly those involving the scenes between Marcello Mastroianni and Sophia Loren), some fine acting, and for anyone who has experienced — or better still, worked at — the Paris Fashion Shows, it is a brilliant, witty and sexy satire, evoking all that is worst in their superficiality and pretentiousness while meditating on (and causing us to reflect sadly on) the amorality of human betrayal for the sake of — not much, in the end. As with "Short Cuts," a lot of unnecessarily prurient attention has focused on scenes involving nudity. If such scenes cause some viewers difficulty, the short answer is that they should not be watching Altman movies, as they will only be made angry and indignant by seeing those scenes out of context.

1994’s Prêt -A- Porter (Ready to Wear) was slammed by many critics, and once again, viewer opinion is harshly divided. The film, which is a shaggy-dog story, actually contains some delicious moments (particularly those involving the scenes between Marcello Mastroianni and Sophia Loren), some fine acting, and for anyone who has experienced — or better still, worked at — the Paris Fashion Shows, it is a brilliant, witty and sexy satire, evoking all that is worst in their superficiality and pretentiousness while meditating on (and causing us to reflect sadly on) the amorality of human betrayal for the sake of — not much, in the end. As with "Short Cuts," a lot of unnecessarily prurient attention has focused on scenes involving nudity. If such scenes cause some viewers difficulty, the short answer is that they should not be watching Altman movies, as they will only be made angry and indignant by seeing those scenes out of context.

An interesting group of Altman-directed movies, uneven, some say bad, others say terrible, came out in the second half of the 1990s. Kansas City (1996), a Depression-era pseudo-gangster movie which has just been re-released on DVD in the US, is a flawed but interesting tribute to his home town, and is dominated by the improvised jazz soundtrack. The Gingerbread Man (1998), starring Kenneth Branagh and Robert Duvall, was a John Grisham adaptation generally reckoned not worth viewing after its opening 15 minutes, yet even this thriller has its moments, and there are fans who like it. Cookie’s Fortune (1999), described as u2018a drowsy Southern comedy’ and starring Glenn Close, was a mediation on life in a small Southern town, and my personal favorite of this group, Dr. T and the Women (2000), starring Richard Gere and Farrah Fawcett, performed the brilliant reflexive trick of having Gere, who has played many Don Juan roles in his time, take the main part of Dr. T., a gynaecologist with a failed marriage who cannot cope with (his) women. And surely only Altman could succeed in having the ever-lovely Farrah Fawcett dance totally nude in a fountain in the middle of a Dallas shopping mall!

All this led up to Altman’s biggest box-office success in years in 2001, the u2018English country house’ 1930s period piece, Gosford Park. I had mixed feelings on first viewing this lavishly decorated film, with once again an all-star cast — all the usual mixed feelings: it was too long, had no real plot, and was at times irritating; but it improved tremendously on second viewing. I think this has everything to do with expectations. We have become so conditioned by Hollywood mainstream fare to expect moronic, fast-paced, shoot-em-up action, posturing instead of acting, and platitudes instead of thought, that when a thought-provoking cinematic experience such as Gosford Park comes along, many are simply too impatient and unskilled at knowing how to absorb and appreciate it, and so react not just with indifference, but with active hostility at having had their own limitations shown up and having been, in their own estimation, cheated.

All this led up to Altman’s biggest box-office success in years in 2001, the u2018English country house’ 1930s period piece, Gosford Park. I had mixed feelings on first viewing this lavishly decorated film, with once again an all-star cast — all the usual mixed feelings: it was too long, had no real plot, and was at times irritating; but it improved tremendously on second viewing. I think this has everything to do with expectations. We have become so conditioned by Hollywood mainstream fare to expect moronic, fast-paced, shoot-em-up action, posturing instead of acting, and platitudes instead of thought, that when a thought-provoking cinematic experience such as Gosford Park comes along, many are simply too impatient and unskilled at knowing how to absorb and appreciate it, and so react not just with indifference, but with active hostility at having had their own limitations shown up and having been, in their own estimation, cheated.

One reviewer has put this issue succinctly: "Director Altman does NOT make films for everyone. He often makes films for the ‘Advanced’ film-goer. His work is often disjointed and overlapping to an extent that it requires one to actually pay attention to the goings-on rather than to spoon-feed the answers to the audience. Couple this with his tendency to allow the plot and the character to meander, evolving slowly over the course of the film, and you often get a movie that is distinctly ‘un-Hollywood’, which can turn some film-goers off. I would recommend that you allow yourself to watch [an Altman film] without any preconceived ideas of how a movie is supposed to be."

So finally to The Company, a 2003 documentary project on the Joffrey Ballet of Chicago suggested to Altman by Neve Campbell, an actress who trained from childhood with the National Ballet School of Canada but was obliged to give up ballet on account of repeated injury. Most critics were unsure of what to make of it, and many of the usual complaints were in evidence in the reviews — that it lacks plot, is neither one thing nor the other or, for one writer, is "a sloppy, ill-focused ramble through the rehearsal process of a top-drawer company." I watched this documentary rather defiantly, in a comfortable movie theatre in which there cannot have been more than half a dozen patrons, as if to prove that, when it comes to Altman, all this doesn’t really matter. Preconceptions about what a movie should be are indeed to be left at the door. Games can be played with the director’s conscious or subconscious references to earlier work, like the ballet which must go on despite (or perhaps in harmony with) a dramatic thunderstorm, echoing the shattering tornado at the end of Dr. T and the Women. "Pleasurable," the word used by the Washington Post’s critic, just about sums it up. I also feel that The Company is a neat, evocative return to the documentary form in which Altman started out, albeit that its effortless sophistication and the luxurious restraint of its sensuous and vulnerable atmosphere now reflect a maturity gained through a lifetime of movie-making.

So finally to The Company, a 2003 documentary project on the Joffrey Ballet of Chicago suggested to Altman by Neve Campbell, an actress who trained from childhood with the National Ballet School of Canada but was obliged to give up ballet on account of repeated injury. Most critics were unsure of what to make of it, and many of the usual complaints were in evidence in the reviews — that it lacks plot, is neither one thing nor the other or, for one writer, is "a sloppy, ill-focused ramble through the rehearsal process of a top-drawer company." I watched this documentary rather defiantly, in a comfortable movie theatre in which there cannot have been more than half a dozen patrons, as if to prove that, when it comes to Altman, all this doesn’t really matter. Preconceptions about what a movie should be are indeed to be left at the door. Games can be played with the director’s conscious or subconscious references to earlier work, like the ballet which must go on despite (or perhaps in harmony with) a dramatic thunderstorm, echoing the shattering tornado at the end of Dr. T and the Women. "Pleasurable," the word used by the Washington Post’s critic, just about sums it up. I also feel that The Company is a neat, evocative return to the documentary form in which Altman started out, albeit that its effortless sophistication and the luxurious restraint of its sensuous and vulnerable atmosphere now reflect a maturity gained through a lifetime of movie-making.

Conclusions

Altman’s films are about damage and about excess, about calling out the inner demons and enemies within, and the diagnostics and therapies we choose — or choose not — to apply in order to cope with, limit or reverse them. Unsurprisingly, they often show the dark side of the psyche, the working out of addictive behavior, the apparent survival of those who "get away with murder," a concept which still jars with a common sense of moral justice, even in these morally befuddled times. They can therefore be profoundly disturbing to those who are afraid to delve into the corresponding depths of mind and soul, or tell themselves that they would just prefer not to have their inner demons exposed.

In contrast to that other great American cinematic master, Woody Allen, who deals in neuro-comedy to touch many of the same subject-matters — psychological vulnerability, love and death, the obsession with celebrity, and the often vacuous nature of urban and suburban inner life, Altman deals with them in a psycho-tragic way which, more than with Woody Allen, offers a ray of hope in the possibility of a radical change when the personal cataclysm finally happens, as it so often does at the end of his films: Dr. T., physically whisked up high into the sky by a tornado, finds himself set down on earth again having to deliver a child somewhere in the Mexican desert. The dysfunctional couples in Short Cuts are all given a second chance by the freak coincidence of an earthquake at a key moment of moral decision.

As he celebrates his 80 years, Robert Altman’s cinematic activity is undimmed. One new movie, Paint, is currently being filmed, while the 2006 title A Prairie Home Companion starring Altman regulars Lyle Lovett and Lily Tomlin as well as Meryl Streep, is in pre-production. When asked about retirement, his oft-quoted rejoinder has been along the lines of "You’re talking about death, aren’t you?" I doubt that even mortality will push this hell-raiser off our screens, because, as both M.A.S.H. and Nashville have shown, his work is enduring. In the meantime, as perhaps the temporary occupant of the White House might care to note, a suitable postscript to Altman’s substantial filmography on this his 80th birthday might be that "no inner demon has been left behind."

Links and Further Reading

Articles

- Lemons, Stephen: Robert Altman, Salon.com — August 15, 2000

- McKay, Brian: Robert Altman: A Lifetime in 90 minutes or Less! Hollywoodbitchslap.com — April 23, 2003

- Self, Robert T.: The Modernist Cinema of Robert Altman, Senses of Cinema — December 2004

- Sterritt, David, Altman, Christian Science Monitor — February 8, 2002

- Usborne, David: Robert Altman: My Films are always the Director’s Cut, Independent — May 14, 2004

Books

- Keyssar, Helene, Robert Altman’s America, 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000

- Kolker, Robert Phillip: A Cinema of Loneliness : Penn, Kubrick, Coppola, Scorsese, Altman, 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Self, Robert T., Robert Altman’s Subliminal Reality — Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2002

Other Resources

- Robert Altman: A Bibliography of Materials in the UC Berkeley Library

- Website: Ward, Christopher: Altman’s Annex

Selected Film Reviews

- Nashville (1975):

Roger Ebert, first review in Chicago Sun Times, January 1, 1975

Roger Ebert, second review in Chicago Sun Times, August 6, 2000

- The Player (1992):

Roger Ebert, Chicago Sun Times, April 1992

- Kansas City (1996):

Hull, Christopher: Kansas City — Filmcritic.com, 2004

- Cookie’s Fortune (1999):

Sragow, Michael: Altman’s Fortune — Salon.com, June 3, 1999

- Dr. T. and the Women (2000):

Danks, Adrian: I Don’t Think We’re in Dallas Anymore — Senses of Cinema, March/April 2001

Dawson, Tom: Robert Altman on Dr. T. and the Women — Channel4.com, 2000

- The Company (2003):

Applebaum, Stephen: Robert Altman on The Company — Channel4.com, 2003

Hunt, Mary Ellen: The Company — Critical Dance, January 2004

Kipp, Jeremiah: The Company — A Film Review — Filmcritic.com, 2003

Quinn, Anthony: The Company — The Independent, May 7, 2004

Thomson, Desson: u2018Company’ — Altman’s Dance Film with Legs, Washington Post, January 23, 2004