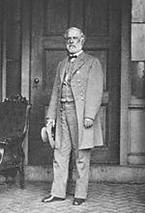

This Sunday is the 196th anniversary of Robert E. Lee’s birthday, and we shouldn’t let the day pass without paying homage to this fine gentleman. In recent years, Lee has become one of the primary targets of the PC campaign to eradicate Southern heritage. But General Lee’s reputation has survived. New books about the "Gray Fox" are still being published even though hundreds of Lee books already exist. Robert E. Lee is the subject of television documentaries and major films portray him in a favorable light. And, of course, there is "the poem."

This Sunday is the 196th anniversary of Robert E. Lee’s birthday, and we shouldn’t let the day pass without paying homage to this fine gentleman. In recent years, Lee has become one of the primary targets of the PC campaign to eradicate Southern heritage. But General Lee’s reputation has survived. New books about the "Gray Fox" are still being published even though hundreds of Lee books already exist. Robert E. Lee is the subject of television documentaries and major films portray him in a favorable light. And, of course, there is "the poem."

Military figures do not ordinarily inspire poets to write about them. But Robert E. Lee was not an ordinary military man. So Donald Davidson, an admirer of General Lee, as well as a defender of Southern principles, was moved to write "Lee in the Mountains" and this poem has become a cult favorite.

Except for Libertarians and advocates of Southern conservative beliefs, Donald Davidson doesn’t have the following he deserves. Davidson was a member of the famous Southern Agrarians, a group of pro-South intellectuals from Vanderbilt University who extolled Southern virtues in the early part of the twentieth century. This group included Allen Tate, Robert Penn Warren, John Crowe Ransom and others. Davidson’s book: "The Attack on Leviathan: Regionalism and Nationalism in the United States" should be required reading for all political science students but you probably won’t find it in any syllabus or any college library.

In his poem "Lee in the Mountains" Davidson depicts Lee in his later years when he was president of Washington College in Lexington, Virginia. As shadows fall in the late afternoon, Lee is walking across the campus when he overhears a group of students whispering, "Hush, it is General Lee!" These words stir the old man’s thoughts.

The young have time to wait But soldier’s faces under their tossing flags Lift no more by any road or field, And I am spent with old wars and new sorrow. Walking the rocky path, where steps decay And the paint cracks and grass eats on the stone. It is not General Lee, young men… It is Robert Lee in a dark civilian suit who walks, An outlaw fumbling for the latch, a voice Commanding in a dream where no flag flies.

Robert E. Lee’s thoughts turn to his father, Lighthorse Harry Lee, the hero of the Revolutionary War, member of congress, and Governor of Virginia. In his mid-50s, bad health forced Harry to seek the warm climate of the West Indies in order to recover his health. Robert was only six years old when his father left the Lee home in Alexandria and sailed for Barbados.

I can hardly remember my father’s look, I cannot Answer his voice as he calls farewell in the misty Mounting where riders gather at gates. He was old then — I was a child — his hand Held out for mine, some daybreak snatched away, And he rode out, a broken man.

While in the West Indies, Harry’s health continued to deteriorate. Fearing that death was imminent, he decided to return to his family but during the voyage the suffering man’s condition worsened. When the ship reached the coast of Georgia, Lighthorse Harry asked to be put ashore on Cumberland Island. He died there a few weeks later and, on the grounds of the Dungeness estate, amidst the live oak and magnolia groves, he was given a full military funeral. Ships at anchor in the gulf fired their guns in salute while soldiers from nearby Fernandina solemnly marched to the graveside with crape on their sidearms.

Now let His lone grave keep, surer than cypress roots, The vow I made beside him. God too late Unseals to certain eyes the drift Of time and the hopes of men and a sacred cause. The fortune of the Lees goes with the land Whose sons will keep it still.

Earlier, before leaving for the West Indies, Harry’s soured real estate deals had eventually caused his financial ruin and landed him in debtor’s prison. In a 12 × 15-foot cell at the county jail at Montross, Lighthorse Harry Lee began writing his memoirs of the Revolutionary War. Upon his release, he completed and published them. Now his son, in his final years, feels compelled to edit and republish his dead father’s memoirs.

What did my father write? I know he saw History clutched as a wraith out of blowing mist Where tongues are loud, and a glut of little souls Laps at the too much blood and the burning house. He would have his say, but I shall not have mine. What I do is only a son’s devoir To a lost father. Let him only speak.

But memories of the long years of the War Between the States disrupt Lee’s thoughts. He is unable to forget the South’s bitter defeat nor can he calm his tormenting doubts about his decision to surrender. The memory of that Palm Sunday at Appomattox continues to haunt the Gray Fox.

The Shenandoah is golden with a new grain The Blue Ridge, crowned with a haze of light, Thunders no more. The horse is at plough. The rifle Returns to the chimney crotch and the hunter’s hand. And nothing else than this? Was it for this That on an April day we stacked our arms Obedient to a soldier’s trust? To lie Ground by heels of little men, Forever maimed, defeated, lost, impugned? And was I then betrayed? Did I betray?

In the waning days of the War, faced with mounting injuries and dwindling supplies, Lee planned to conceal his remaining soldiers in the mountains of North Carolina and use guerilla-style raids on the enemy until a new army could be formed. General Washington had successfully employed this technique during the Revolutionary War when, like Robert E. Lee, his forces had also been outnumbered. But Confederate President Jefferson Davis had turned down Lee’s request. Now Lee wonders what might have happened if Davis had not rejected his plans.

Too late We sought the mountains and those people came. And Lee is in the mountains now, beyond Appomatox, Listening long for voices that will never speak Again; hearing the hoofbeats that come and go and fade Without a stop, without a brown hand lifting The tent-flap, or a bugle call at dawn, Or ever on the long white road the flag Of Jackson’s quick brigades. I am alone, Trapped, consenting, taken at last in mountains.

The sound of a chapel bell interrupts Lee’s reverie, his mood suddenly changes, and he is overcome with a powerful religious conviction.

Young men, the God of your fathers is a just And merciful God who in this blood once shed On your green altars measures out all days, And measures out the grace Whereby alone we live.

The religious motif that brings Davidson’s poem to this passionate conclusion is foreshadowed throughout this remarkable composition. There is a feeling of reverence surrounding Lee’s attachment to the land, his pride in his famous family, his paternal feelings toward his students, and his unceasing devotion to the memory of his heroic father.

In the last year of his life, Robert E. Lee, accompanied by his grown daughter, Agnes, took a tour of the South. Their stopover in Savannah was particularly poignant because Lee made what he sensed would be his last visit to his father’s grave. On an April morning, Lee and Agnes took a steamer to Cumberland Island. Lee stood by in silence while Agnes placed beautiful fresh flowers on her grandfather’s grave.

Within a few months Lee himself passed on and was buried in the crypt beneath the chapel at Washington College. Years later, Harry Lee’s body was removed from Dungeness and placed in the crypt beside his son. Now all the Lees were home again in their beloved Virginia. As Davidson reminds us: