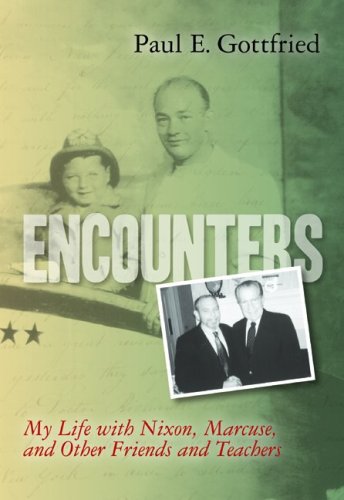

Encounters: My Life with Nixon, Marcuse, and Other Friends and Teachers, by Paul Gottfried, ISI Books, 275 pages

Professor Paul Gottfried, who calls himself a “historically centered traditionalist who admires the bourgeois civilization that had dominated the West in the nineteenth century,” has written a first-rate memoir of some of his most cherished encounters with prominent politicians and intellectuals.

Gottfried shrewdly avoided taking the conventional autobiographical route through his life and has instead produced a series of narratives relating to his scores of fascinating friendships with those he calls professional nonconformists or “figures who have represented the true dissenting academy.” Thus, Gottfried’s latest book gives us a series of revelations of his spirited engagements with some of the intellectual community’s most engaging minds.

The author is a “conventionally observant” Jew whose father left Central Europe to escape the competing tyrannies that had begun to emerge prior to the Second World War. His flawed but courageous and rebellious father, born in Budapest, is a focus of the book early on. The elder Gottfried profoundly influenced his son’s perspective and opinionated demeanor, both of which have led Paul to resist the conformist pressures of his chosen career as historian and teacher. That resistance has cost him friends.

Encounters: My Life wi...

Best Price: $5.20

Buy New $5.60

(as of 08:10 UTC - Details)

Encounters: My Life wi...

Best Price: $5.20

Buy New $5.60

(as of 08:10 UTC - Details)

But Gottfried’s lack of popularity among his colleagues in academia has not prevented him from leading a life that, he says, “has gone nowhere in particular but has nonetheless been packed with fascinating encounters.” During his graduate stint at Yale, he met the German-Jewish scholar Herbert Marcuse, a theorist of the neo-Marxist Frankfurt School. Marcuse’s Old World carriage and extraordinary lectures attracted the young Gottfried, who became enthralled with European intellectual history and German philosophy. (Marcuse, in fact, was admired by a diverse group of young scholars — the conservative philosopher and economist Hans-Herman Hoppe also studied under Marcuse at Goethe University in Frankfurt.) The significance of Marcuse as a scholarly influence in Gottfried’s life is summed up when the author concedes that he “learned true liberal intellectual exchange from a declared Marxist-Leninist.”

Perhaps the principal lesson contained within Encounters is that Gottfried’s enviable intellectual life has not been without its pitfalls. Early on, his frequent dissent on issues that were critical to the ambassadors of multiculturalism led to his marginalization by the liberal academic establishment.

Not surprisingly, Gottfried is among the most candid and gifted of the conservative historians who have challenged the notion that neoconservatives are a part of the Right. He condemns them as “paradigmatic leftists who are counterfactually identified as ‘conservatives.’” Three main problems that Gottfried sees with the neocon-dominated establishment conservatives is their desire to enforce democracy all over the world, their support of gender politics, and their politically correct position on immigration. His historic battles with neoconservative ringleaders ultimately led to him being denied a professorship at Catholic University, as well as the defeat of his potential chairmanship at the National Endowment for the Humanities in 1986. Hence his assertion, “The refusal to call neoconservatives what we are supposed to call them may be politically and professionally imprudent.” Still, he challenges the neoconservatives when they resort to employing the “conservative” moniker in their quest for social progress through an extensive welfare state and egalitarian agenda. He writes:

Both their enthusiasm for Third World immigration and their opposition to immigration restrictionists flow from their view that populations are interchangeable. All people are ‘individuals’ who can be socialized in the same way, providing they are molded by a suitable public administration and by a steady diet of human-rights talk. Because, like the earlier progressives, the neoconservatives associate public education with ‘democratic patriotism,’ and because they link morality to ‘democratic values,’ they have been allowed to appropriate for themselves the ‘conservative’ mantle. This, in my opinion, is a case of mistaken identity.

At the Tennessee farm, July 2009.

At the Tennessee farm, July 2009.

Furthermore, his scholarly work has outlined the proper distinctions between the post-war, socially progressive, neoconservative Right and their critics who are genuinely on the Right. Gottfried calls this the “airing of dirty linen.”

In his life, Gottfried has been inspired by a host of eccentrics who cannot easily be typecast along ideological lines, including the Communist-turned-religious-conservative Will Herberg, a Jewish theologian who once noted that “anti-Catholicism is the anti-Semitism of secular Jewish intellectuals.” There was also Christopher Lasch, a social critic and communitarian who cast aspersions on the narcissistic culture of consumer capitalism and bemoaned much of contemporary political thought in America, infuriating intellectuals on both the Left and Right. Gottfried at first became an adversary of Lasch — lost out on a professorship at the University of Rochester due to “Lasch’s politicking” and Gottfried’s own reputation as a Nixon Republican. Twenty years later, however, the two were friends, though it’s not clear what transpired in the years in between.