Walter Block has invited us to provide some autobiographical background on how we came to be Misesians/Rothbardians. This is my contribution to the cause.

Jerome Tuccille wrote a book thirty years ago, It Usually Begins With Ayn Rand. It was a good book, especially the sections on the Galambosian, but it was wrong. Back when he wrote it, it usually began with The Freeman.

Today, it usually begins with LewRockwell.com.

I remember the lady who first handed me a copy of The Freeman. It was in 1958. She was an inveterate collector of The Congressional Record. She clipped it and lots of newspapers, putting the clippings into files. She was a college-era friend of my parents.

She was representative of a dedicated army of similarly inclined women in that era, whose membership in various patriotic study groups was high, comparatively speaking, in southern California. These women are dead or dying now, and with them go their files — files that could serve as primary source collections for historians of the era. I suspect that most of them disposed of their collections years ago, cardboard box by cardboard box, when they ran out of garage space, and their nonideological husbands and children finally prevailed.

Back then, someone had already coined a phrase to describe women like her: little old lady in tennis shoes. But she wasn’t that old, and she didn’t wear tennis shoes. In fact, in all my days, I only saw one ideological little old lady in tennis shoes: Madalyn Murray O’Hair, who stood in front of the humanities departments’ building at the University of California, Riverside, to lecture to maybe 20 students. That was over a decade after I read my first issue of The Freeman. By then, I was writing for The Freeman.

ANTI-COMMUNISM

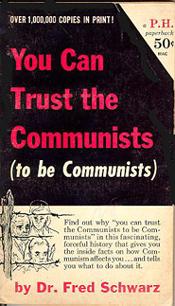

My main academic interest in 1958 was anti-Communism. In 1956, the lady had taken me to hear the anti-Communist Australian physician Fred Schwarz, when I was 14, in one of his first speaking tours in the United States. Shortly thereafter, I sent Schwarz’s Christian Anti-Communism Crusade $100 ($650 in today’s money), which were big bucks for me. I had been working in a record store after school for $1 an hour for only a few months.

My main academic interest in 1958 was anti-Communism. In 1956, the lady had taken me to hear the anti-Communist Australian physician Fred Schwarz, when I was 14, in one of his first speaking tours in the United States. Shortly thereafter, I sent Schwarz’s Christian Anti-Communism Crusade $100 ($650 in today’s money), which were big bucks for me. I had been working in a record store after school for $1 an hour for only a few months.

My parents were conservative Republicans. My father was in the FBI. He monitored “the swoopers” — the Socialist Workers Party, a Trotskyite splinter group. Once in a while, he would put on his Sherman Williams Paint (SWP) cap for effect. But he wouldn’t wear it while surveilling the Trotskyites.

Sometimes, dad would be called in to monitor “the real stuff”: the local Communist Party. He told me that one night, after a CP rally, the local leader of the Party, Dorothy Healey, got into her car, looked behind her at my dad’s car, and waved her arm to follow. Then she pulled into traffic and drove away. He, of course, followed her. (I was disappointed that she didn’t put this incident in her 1990 autobiography, Dorothy Healey Remembers.)

To give you some idea of how conservative dad was, when the U.S. Government suggested that employees drive with their lights on out of respect to the anniversary of Martin Luther King’s assassination, dad drove home that evening with his lights off, risking a ticket and a collision. Yet he was one of the four Los Angeles FBI agents who discovered evidence that identified James Earl Ray as King’s assassin, for which he was happy to take credit. He did his work as a professional.

In the summer of 1958, I went to Boys State, a week-long program in state government sponsored by the American Legion — Bill Clinton attended in Arkansas a few years later — and that experience matured me more in one week than anything ever has. It was there that I gained my confidence to speak in public. I was elected to a state-level office. Ironically, the office was Superintendent of Public Instruction. That success gave me the confidence to run for student body president the next semester. I won. I did it with a comedy speech that poked fun at the system.

Another Boys State attendee that year was Dwight Chapin. He later served as Nixon’s appointments secretary. He went to jail because he was the in-house contact man for Bob Segretti, of dirty tricks fame. In March, 1970, I contacted Chapin for a job. He agreed to help me get one. It did not work out.

I remember in the fall of 1958, when I was researching a 15-page, double-spaced term paper on Communism for a high school civics class, that the lady handed me my first copy of The Freeman. We got into a discussion about civil government. She was opposed to tax-funded education. I was amazed. She also did not trust the FBI, which she said was a national police force, which the U.S. Constitution did not authorize. I was even more amazed. It was then that I began my odyssey from anti-Communism to free market economics.

There was another key figure in my life: Wayne Roy. He taught civics (“senior problems”) at Mira Costa High School in Manhattan Beach. (Its most famous graduate was surfer Dewey Weber, class of ’56, who lives on beyond the grave because of the Dewey Weber T-shirt worn by Mackenzie Phillips in George Lucas’ film, “American Graffiti.”) Mr. Roy was the best social studies teacher on campus, and by far the hardest grader. I requested to get into his class, and I became his best student that year. He was a fundamentalist and a conservative. I was not yet interested in religion, but I liked his conservatism.

He actually discussed Christianity in the classroom, especially in the required marriage and family section. He later became notorious among liberal educators in Southern California after the Supreme Court decisions on religion and public education came down in the early 1960’s. He refused to pay any attention to the Court. Educators from outside the school district tried to get him fired, but they were not successful.

In the spring of 1959, he explained the economics of Social Security. He told us that it was actuarially unsound and that it would go bankrupt before most of us died. He primed us on questions to ask the local Social Security PR flak who came to every school in the district every year to promote the program. In the man’s retirement year, he told Roy that his were the only classes where students ever asked him tough questions.

COLLEGE

I have previously discussed the influence that Robert Nisbet had in my career, beginning in 1960. At the University of California, Riverside, I was one of fewer than two dozen visible conservatives on a campus of 1,000. I was the only one involved heavily in campus politics. The campus doubled in size during my stay, but the number of conservatives didn’t.

Here is what I read. First and foremost, National Review. In 1961, one issue included a stapled insert: Dorothy Sayers’ 1947 essay, “The Lost Tools of Learning,” a masterpiece. I read selected essays in The Freeman and Modern Age, and faithfully read the little-known monthly booklet, Intelligence Digest, published in Britain by Kenneth de Courcy. I also read Russell Kirk’s University Bookman, which was sent free to National Review subscribers. That was a very influential little quarterly journal in my thinking.

I began subscribing to New Individualist Review with the first issue in April, 1961. That was where I first read Milton Friedman. The NIR ran an extract from Capitalism and Freedom in the first issue. That issue was also where I read the first libertarian critique of Hayek that I ever encountered, an essay by Ronald Hamowy, “Hayek’s Concept of Freedom: A Critique.” The NIR was edited by Ralph Raico and published by a group of students at the University of Chicago who were associated with the I.S.I. (On the I.S.I., keep reading.)

In that same year, I contacted F. A. Harper at the William Volker Fund. I asked him a question regarding Human Action. I had caught Mises in what I still think is a conceptual mistake, his discussion of the Ricardian law of association, where he used simple mathematics in an illegitimate way (HA, 1949, p. 159.) Harper replied in a letter. I still keep it in my 1949 edition of Human Action. He said he agreed with me on this point. He soon invited me to Burlingame to visit. He offered to pay for the flight. I took his offer. “Baldy” Harper, who was not bald, had been with the Foundation for Economic Education (FEE) until his defense of zero civil government led to a break with Leonard Read. He then went to work at the Volker Fund.

The Volker Fund was the one libertarian foundation with any money in 1961. It was very low key, as its late founder, William Volker (“Mr. Anonymous”) wanted. Through its front, the National Book Foundation, the Volker Fund gave away libertarian books, such as Böhm-Bawerk’s, to college libraries. Writing book reviews for the Fund were Murray Rothbard and Rose Wilder Lane, although I did not know this at the time.

Harper was a master recruiter. He was a trained economist, a former professor at Cornell University, along with W. M. “Charlie” Curtiss. Both of them had joined FEE in its first year, 1946. One of their students was Paul Poirot, who was became editor of The Freeman. It can be said that academic libertarianism was born at Cornell, though not nurtured there.

Harper wrote a few books, most notably, Liberty: A Path to Its Recovery, but his main contribution to libertarianism was his systematic recruiting of young scholars. In 1961, he was publishing the William Volker Fund series of books, most notably Man, Economy, and State, which he sent me in the fall of 1962. Also in the series was Israel Kirzner’s Ph.D. dissertation, The Economic Point of View (1960), which was a rarity: a Ph.D. dissertation worth reading.

In the spring of 1962, I attended a one-week evening seminar given by Mises. It was sponsored by Andrew Joseph Galambos, one of the oddest characters in the shadows of libertarian history. He believed that all original articulated ideas possess automatic copyright, which is permanent, and no one has the right to quote someone else’s ideas without paying a royalty to the originator or his heirs. Galambos was influential in shaping Harry Browne’s thinking, as Browne has discussed in a 1997 essay. The seminar was held during the period when Human Action was out of print. Yale University Press was in the process of typesetting the monstrosity that appeared in 1963, the New Revised Edition. (Henry Hazlitt, “The Mangling of a Masterpiece,” National Review, May 5, 1964.)

In the summer of 1962, I attended a two-week seminar sponsored by the Intercollegiate Society of Individualists — now called the Intercollegiate Studies Institute — at St. Mary’s College in California. I had been on the I.S.I. mailing list for about two years. I read The Intercollegiate Review. During that seminar, I listened to Hans Sennholz on economics, and I slept through Francis Graham Wilson’s Socratic monologues on political theory. I heard Leo Paul de Alvarez on political theory. I remember nothing about his lectures, but I’m sure they were suitably arcane. He was a Straussian. Rousas John Rushdoony lectured for two weeks on what became This Independent Republic (1964). I was so impressed that I married his daughter — a decade later.

What I did not recognize at the time was that there had been a change of administration at the Volker Fund. The director, Harold Luhnow, who was Volker’s nephew, had fired Harper and had brought in Ivan Bierly, another ex-FEE senior staffer, and also a Cornell Ph.D. Bierly then hired Rushdoony. He also hired the strange and erratic David Hoggan (HOEgun), a Harvard Ph.D. and a defender of Hitler’s foreign policy (The Enforced War). When in his cups, he was a defender of Hitler’s domestic policies, too. He had already written the manuscript for his anonymously published book, The Myth of the Six Million, published years later. There have been many strange figures in the conservative movement, but when it comes to academic types, Hoggan was the gold medalist in weird. He could provide footnotes, not all of them faked, in eight languages. There was nothing libertarian about him. The other major figure on the staff was W. T. Couch, a former Collier’s Encyclopedia editor, and a man who rarely bathed. There was nothing libertarian about him, either. The Volker Fund was put on hold, replaced by the short-lived Center for American Studies (CAS). A decade later, the Volker Fund’s money went to the Hoover Institution.

A SUMMER OF READING

Rushdoony hired me as a summer intern at the CAS after my graduation in June, 1963. I was paid $500 a month to read, which was the best job I have ever had. I read books that I had wanted to read in college: The Theory of Money and Credit; Socialism; Man, Economy, and State; America’s Great Depression; and The Panic of 1819. I read Wilhelm Roepke’s A Humane Economy and Economics of the Free Society. I read Bohm-Bawerk’s Positive Theory of Capital. I also read a lot of typed book reviews by Rothbard and Lane, which were in the files. I also read Cornelius Van Til’s The Defense of the Faith. I had already decided to attend Westminster Theological Seminary that fall, to study under Van Til.

That summer, I spent every extra dollar I had to buy silver coins at the local bank. Sennholz had convinced me the previous summer that Gresham’s Law would soon eliminate silver coins, because silver dollars, which had a higher silver content, were already disappearing. I sold my coins to my parents to pay for seminary. They kept the coins, selling them only after silver’s price soared. Silver coins started disappearing that fall. Turnpike officials in the East Coast had to go to churches on Sunday nights to buy coins tossed into collection plates.

GRADUATE SCHOOL

I lasted at seminary for one year. I could see the handwriting on the wall. It was going from right to left.

I enrolled at UCLA in the fall of 1964 to study economics. The department’s war was on: the Keynesians vs. the Chicago School people, and I was caught in the crossfire. I dropped out and transferred back to UC Riverside, where I enrolled in the history program. I remained there until 1971, when I joined FEE’s staff. I was awarded my Ph.D. in the summer of 1972.

The main influences on me in graduate school were these: Nisbet; medievalist Jeffrey Burton Russell; Douglas Adair, a specialist in the American Revolution and the reigning expert on who wrote which essays in The Federalist Papers; Herbert Heaton, aged yet still teaching, one of the founders of economic history as an academic specialty; Hugh G. J. Aitken, another economic historian and later the editor of The Journal of Economic History; and Edwin Scott Gaustad, a specialist in American religious history. I also banged heads with Marxist economist and science fiction aficionado, Howard Sherman, who was a nonideological grader and who shared my suspicion of the usefulness of simultaneous equations in economic theory.

Nisbet was a great lecturer, but day in and day out, the best classroom lecturer I ever heard in my entire academic career was Roger Ransom, another economic historian. His book, One Kind of Freedom, on the economics of sharecropping in the Reconstruction era, remains a standard work. It shows that sharecropping was an economically rational response to the post-war shortage of capital in the South.

I received two fellowships: the Earhart Foundation (two years) and a Weaver Fellowship from the I.S.I. That one came the second time I applied. I think the fact that I had published a book, Marx’s Religion of Revolution (1968), and had been publishing in The Freeman since early 1967 helped. I was a teaching assistant in Western Civilization for three years. This enabled me to see just how committed students were to academic pursuits. I decided that if I could avoid college teaching, I would.

The Ph.D. glut hit right on schedule in the spring of 1969. The date of this event had been predicted for several years, and the prediction was accurate. The state’s subsidy to education (increased supply of graduates), coupled with the slowdown in university hiring (tenure positions filled), created a double whammy that is still in progress a generation later. I saw that the Ph.D. was no longer a union card. It was a membership card in the reserved army of the unemployed. But, in utter defiance of the doctrine of sunk costs, I decided to complete my degree.

In 1971, I was offered a job at the James Madison College of Michigan State University, but I turned it down. I think I know why I got the job offer. I was lecturing on medical licensing, which I opposed. At the conclusion, the most liberal member of the college’s faculty responded. “It sounds to me as though you are recommending that consumers should be supplied with Fords rather than Cadillacs.” I don’t know where my response came from. “I’m just trying to reduce demand for used Hudsons.” Student laughter ended the discussion.

FEE

When George Roche left FEE in 1971 to take over as president of Hillsdale College, where he hired Lew Rockwell to launch the most effective fund-raising newsletter in history, Imprimis, Leonard Read offered me Roche’s job at FEE. I joined the senior staff in September, 1971, as Director of Seminars. This entitled me to ask the secretary who ran the program, “Have you sent out cards to applicants saying, ‘We have received your application’?” and be told, “We don’t do it that way.” But I got paid on time. I now had enough money to get married.

I could see that FEE was an appendage of Read, and he was not going to let FEE grow beyond what it already was: a place for him to schmooze and for Poirot to edit The Freeman. The week that I arrived in Irvington, Read informed me of his policy that FEE would receive every dime I would ever earn in my off-hours, such as fees for writing and lecturing, which were what I did best. I saw that this would hurt my career in the long run. At $18,000 a year, I had counted on outside income to enable me to compete with stockbrokers in the local real estate market, which was merely high priced then, rather than astronomical, which it is today — the main reason why FEE has not been able to hire full-time young scholars since 1973. If Read had allowed a 50-50 split, I might have stayed, but FEE was too bureaucratic for my tastes. I began plotting my escape the week I arrived. I quit FEE sometime in March, 1973, to sell silver coins. Harry Browne was working for the same company, now known as Monex. We both conducted evening seminars. He got the big cities. I got the leftovers.

I started my newsletter, Remnant Review, in May of 1974. In late 1973, René Baxter, a financial newsletter writer and coin salesman, stopped me in the hall at a conference of the Committee on Monetary Research and Education, and asked me: “Why don’t you start a newsletter?” I had no good answer.

If I had still been with FEE, I would not have started my newsletter. Read would have vetoed the idea, and even if he didn’t, FEE would have received all of the money. Leaving FEE was one of my better decisions.

Nevertheless, I owe a great deal to FEE. Paul Poirot launched my national career by publishing almost everything I submitted to The Freeman. The money helped put me through grad school. His editorial policy was simple: all or nothing. He sent back a submission if he did not like it. He did not alter the author’s text. He did add bold-faced headings if the author didn’t, so I started adding my own. This affliction has never left me. I cannot write without headings. I even ad sub-headings in my books.

In the summer of 1973, I went on staff at my father-in-law’s Chalcedon Foundation. I was the second full-time employee. I made $1,000 a month with no benefits: retirement or medical insurance. I started my newsletter less than a year later. He let me mail my first promotional piece free of charge in his newsletter. That was what launched my publishing career.

In 1974, I attended the now-famous Austrian Conference at South Royalton, Vermont, sponsored by Harper’s Institute for Humane Studies. Harper had died the year before. There, a few months after Mises had died, and a few months before Hayek won the Nobel Prize, the troops assembled. The old warriors were there: Rothbard, Kirzner, Ludwig Lachmann, Hazlitt, W. H. Hutt (of “consumer sovereignty” fame), and William Peterson. Younger faces included Jack High, David Henderson, Richard Ebeling, Shirley Letwin, Karen Vaughn, Laurence Moss, Walter Block, Walter Grinder, Sudha Shenoy, Joseph Salerno, Roger Garrison, Mario Rizzo, D. T. Armentano, Don Lavoie, and Gerald O’Driscoll. Milton Friedman even showed up to deliver an evening lecture.

It was at that meeting that Walter Block and I first met. We found a common interest: our sense of outrage at R. H. Coase’s famous theorem. I recall Block’s succinct theoretical objection to Coase’s theorem: “Coase, get your cattle off my land.” That pretty well summarizes my position.

That conference was a major event in the recovery of the Austrian economics movement. Out of that conference came The Foundations of Modern Austrian Economics (1976). Edwin Dolan had persuaded Cornell University’s economics department to allow our little group to meet there, but then they reneged, even though Dolan was on the faculty. The South Royalton School of Law was a fall-back position in every sense. We therefore can trace early academic Austrianism in America from Cornell to Cornell (almost).

WASHINGTON INTERLUDE

I joined Ron Paul’s staff in June, 1976. He had just been elected to Congress after the incumbent Democrat resigned to take a bureaucratic job. Congressman Larry McDonald had told Paul that I was available. (Seven years later, McDonald disappeared on Flight 007, which we are told crashed, leaving no bodies or debris. Some people still believe this official version. I don’t.) It turned out that Paul was a subscriber to Remnant Review, or so I recall. I joined his staff as his research assistant. I even got a parking place. That was back when you could by a 2,500 square foot brick home in the Washington suburbs for $85,000.

It was an amazing staff. Bruce Bartlett was on it. He was an M.A. in history, author of The Pearl Harbor Cover-Up. He later went on to become Jack Kemp’s staff economist. There was John Robbins, a Ph.D. in political science, a former Sennholz student, a Calvinist, and a disciple of philosopher Gordon Clark, Van Til’s nemesis. We shared the same back office.

I wrote a weekly newsletter for Paul. I wrote it as every journalist writes: on the day it was due. It included a bi-weekly column, “Where Your Money Goes . . . and Goes . . . and Goes.”

When he was defeated by 268 votes out of 183,000 in November, I went looking for another job on Capitol Hill. My friend Stan Evans, who had just started the National Journalism Center — a terrific organization, by the way — had recommended me to his old friend, an incoming Congressman from Indiana, Dan Quayle. Quayle told Evans to have me contact his administrative assistant. I did. My experience with that ideologically gray sludge, stonewalling, flank-protecting character persuaded me to leave Washington. I wrote an issue of Remnant Review, “Confessions of a Washington Reject,” which burned whatever bridges might have remained. Then I moved to Durham, North Carolina, where I became a non-paying user of Duke University’s magnificent library.

If I had gotten that job with Quayle, I might have worked with William Kristol, who ran Quayle’s Senate and Vice Presidential offices. I had met Kristol at a Philadelphia Society meeting in 1969, when he was 17, at which time R. Emmett Tyrrell recruited us to write for The Alternative, later called The American Spectator. Somehow, I don’t think our relationship would have worked out.

I joined the staff of Howard Ruff’s newsletter, Ruff Times in early 1977. I worked for Ruff until the fall of 1979. Ruff’s was the first hard money letter to gain a mass audience.

In the fall of 1979, I was appointed to the chair of free enterprise at Campbell University in North Carolina, a position that William Peterson had previously held. That semester was my one and only full-time position in academia. By that stage of my newsletter-publishing career, North Carolina’s income tax was going to cost me more than what the position paid. I moved to Texas in late December: no state income tax.

MY LIFE’S WORK

I decided at age 18 that I would try to discover the relationship between the Bible and economic theory. I was persuaded by The Freeman that Mises had the correct approach: market freedom. But I had become a Christian at age 17, and I was convinced in 1960 that the Bible applies to all areas of life, including economics. I wanted to know if Mises’ economics related to the Bible. My first published effort in this regard was my book, An Introduction to Christian Economics (1973).

In the spring of 1973, my wife persuaded me to begin writing an economic commentary on the Bible. I published my first chapter in the May, 1973, issue of my father-in-law’s newsletter, Chalcedon Report. I recently completed St. Paul’s first letter to Timothy. This is volume 13 in the series: Genesis, Exodus (3 volumes), Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, Matthew, Luke, Acts, Romans, I Corinthians, and I Timothy.

There are also about ten volumes of appendixes and supplements, including my story of the coup d’état that produced the United States Constitution: Political Polytheism, Part 3. These books are all on-line for free at www.freebooks.com. One volume is my hatchet job on R. H. Coase’s theorem, which I published as a book in 1991, The Coase Theorem: An Essay in Economic Epistemology. I am happy to say that a short version of that book is scheduled to appear in an upcoming issue of The Journal of Libertarian Studies.

Since 1977, I have devoted ten hours a week, fifty weeks a year, to this commentary project. I plan to cease working on it at age 70 and write a treatise on Christian Economics. The section on socialism I intend to call, “The Devil Made Me Do It.”

CONCLUSION

What have I learned so far? This: “Stick to your knitting.” Decide what you want to leave behind, and begin working on it as soon as you decide, systematically, week by week, until they find you lying face down on your keyboard, with a screen filled with a single letter.

On my tombstone, I shall leave behind this assessment of my career: “O deadline, where is thy sting?”

December 16, 2002

Gary North is the author of Mises on Money. Visit http://www.freebooks.com. For a free subscription to Gary North’s twice-weekly economics newsletter, click here.

Gary North is the author of Mises on Money. Visit http://www.freebooks.com. For a free subscription to Gary North’s twice-weekly economics newsletter, click here.