How the Gunfighter Killed Bourgeois America

by Ryan McMaken by Ryan McMaken

If there is a single genre of literature and film that defines the 20th century, it is the Western. As the popularity of the Western began to decline in the 1960’s, far more Western films had already been made than films of any other genre. Countless television Westerns had dominated the airwaves for decades, and the iconic gunfighter had become one of the most recognized characters ever in American popular culture.

In time, the gunfighter would come to be used as a symbol of America itself. Even in the early days of the 20th century, when the Western was just beginning to take shape as a literary genre, politicians, intellectuals, and political hacks of every stripe, knowing the grip that the romance of the frontier held on the American psyche, identified themselves, and whatever political agenda they happened to be pushing, with the gunfighter and the Old West. The morally unambiguous gunfighter, and his natural habitat, the Wild West, would come to represent a world where life was supposedly more pure, simple, and virtuous. Theodore Roosevelt pioneered the use of the frontier as a rhetorical device in ideology and politics, and by the time the Cold War was in full swing, Westerns and their heroic gunfighters were widely accepted as an analogy for America’s place in the international community. There were good guys and bad guys and nothing in between, and this simplified version of reality would prove to be quite attractive.

The traditional or "classic" Western would dominate American popular culture for over half a century and become an essential source of American iconography throughout much of the 20th century. While the later Westerns (produced after 1965 or so) would stray from the formulas of the traditional Westerns, they would never quite abandon the genre’s fundamental themes. Nevertheless, the classic Westerns of mid-century are regarded as the "purest" form of the Western, and their fans continue to regard them as the high point of the genre.

A case in point is the modern right-wing’s attachment to the Western. Since it has always been seen as a commentary on the role of the American state and American society in the world, the Western continues to be revered by American Conservatives and libertarians who have convinced themselves that the decline of the Western’s popularity must somehow be connected to American nihilism, political correctness, or some other deplorable development in American society. The greatness of the Western, they maintain, stems from its strict adherence to good old-fashioned American values. They tell us that the mythos surrounding the gunfighter and the frontier in Western films is a wonderful mythos because it reflects the true foundations of America.

If this were the case, then the Western would have to reflect the values of bourgeois liberalism, the ideology that dominated American society from colonial days through the 19th century. The Western is quite disconnected from this tradition, however, and is in fact far more in line with very anti-liberal values that began to dominate America and Europe during the 20th century. As I will show below, the Western, at its core, is a genre fundamentally opposed to the bourgeois and liberal ideals that dominated 19th century American society. Western-type literature never found a large audience among Americans of the 19th century, but the Western would find a very large and enthusiastic audience among Americans of the 20th century who would largely abandon classical liberalism for new ideas of nationalism, socialism, and an ever-expanding American State.

The Western and Liberalism

Very often, defenders of the Western associate it with liberty, private property, and suspicion of government power. That is, the Western is associated with classical liberalism, the dominant ideology of 19th century Western Europe and America, where limited government, liberty, and free enterprise became the darling ideals of a new class of bourgeois elites. And, while in theory liberalism as an ideology could exist anywhere at any time, liberalism has only ever dominated the political landscape where bourgeois middle classes have had significant influence. Historically, the story of liberalism is inseparable from the history of bourgeois liberalism.

Believing themselves to be the heirs of this tradition, many right-wing defenders of the Western, accepting the assumption that the Western defends traditional American values, staked their claim on the Western decades ago, and there remains a lingering loyalty to the Western as a distinctly liberty-loving genre. It is simply assumed that, since in the real West, bourgeois middle class societies built an advanced and free society in the wilderness, the Western genre must reflect the same values that made it all possible.

This is a very bad assumption. Since the beginning, the Western has masqueraded as history. It has claimed to be the "story of America" and as a true, albeit embellished, telling of the settling of the West in the 19th century. Yet, we don’t find much of the 19th century in the 20th century Western at all. The Western genre, whether in film or in literature, is in fact strictly a product of the 20th century, reflecting the politics and values of an age that came only after the Old West was a thing of the past. The typical elements of the Western are all part of a world created in the 20th century to represent a world that might have existed in the 19th century, but did not.

The classic Western, it turns out, centers not on bourgeois values of commerce, hearth, and home, but on martial values of courage, honor, and power through violence. Perhaps there is nothing to dislike about values such as courage and honor, yet what we find in the Western is that these values, as personified in the gunfighter, are not complementary values to the bourgeois world, but are in fact mutually exclusive. Through this literary device, the Western turns the value system of the historical frontier on its head. In the 19th century, bourgeois values dominated (many historians would even describe this dominance as "hegemonic") both in the settled East and on the frontier. But in the Western, bourgeois values are viewed not just as irrelevant, but as a hindrance to the settlement of the frontier. What is essential to the settlement of the frontier in the Western, is the frequent application of deadly force upon both the White and Indian denizens of the frontier.

That the classic Western is an apologia for American expansionism and "militant Anglo-Saxonism," (as Richard Etulain calls it) has been forwarded quite thoroughly by historians and critics of popular culture (such as John Cawelti and Tom Englehardt) for many years. I will not attempt here to prove such theories all over again. Instead, I will focus on the misconception that the nationalistic and authoritarian subtext of the Westerns is friendly toward the American bourgeois culture of the 19th century. In fact, it is clear that the Western does not defend 19th century liberal values at all, but actually repudiates them. The result is that in the universe of the typical traditional Western, the values of the gunfighter are necessarily at odds with the values of the bourgeois America he is supposedly defending.

In the typical Western, the bourgeois society must subject itself to the authority of the gunfighter or face annihilation. The gunfighter exists as a personification of the State on the frontier, and the choice that faces the townsfolk is to either accept the supremacy of the gunfighter or to accept oppression at the hands of Indians, outlaws, or worse. Self-defense is rarely an option, for the bourgeois settlers, consumed by their petty commercial and domestic pursuits are incapable of handling themselves in a dangerous and chaotic world.

To establish ideal conditions for the extension of this militaristic fable, the Western makes two assertions that are central to the life of the genre. First, it creates the image of an American West that is extremely violent. Second, the Western requires that the residents of the frontier be incapable of defending themselves so that they may only be saved after they abandon their naïve bourgeois ways and embrace militarism as their only hope in avoiding destruction.

I will not deal here with the issue of how violent the historical West really was. Since the 1970’s there has been a growing body of research debunking the myth of the bloody and wild West (see here and here). What I will focus on here is the obsession that Westerns have with violence, the virtues of militarism, and the heroic stature of the gunfighter at the expense of all other players in the story of the West. We find that again and again, the Western sets up a tale of gunfighters (themselves almost supernatural in their wisdom and invincibility) who are beyond the comprehension of ordinary polite society. The gunfighter serves a messianic role on the frontier as he saves the bewildered townspeople from their enemies, pulls them away from their petty private concerns, and unifies them in a struggle against evil.

While the gunfighter ascends to levels of great virtue in the Western, the institutions of peaceful and private society are regularly mocked and portrayed as corrupting at best and ridiculous at worst. Businessmen, intellectuals, and religious figures are generally treated with thorough contempt, further solidifying a preference for force over reason within the genre. So, while we know that the landscape of the historical West is primarily a landscape of farms, ranches, shops, churches, and homes, the landscape of the cinematic West is a landscape of war inhabited primarily by gunmen and their victims. This focus on the frontier society’s dependence on the gunfighter pushes all institutions of civilization to the margins, and produces a genre that portrays constant violent conflict as a romantic and redemptive activity. Meanwhile, religious devotion, economic pursuits, and domestic concerns are shown to be secondary activities, and as superfluous luxuries that owe their very existence to the quick draw of the gunfighter.

In the traditional Western, the gunfighter is part Nietzschean bermensch and part Hobbesian Leviathan rolled into one. He exists to enlighten others and to impose order on a dangerous world simply by virtue of being more proficient at the use of force than his enemies. He is always a man apart. He is above the contemptible pursuits of ordinary daily life, and only after order is imposed by the gunfighter is peaceful civilization possible. The classic Western thus comes to an important conclusion: without the gunfighter, civilization is impossible.

John Ford

John Ford

Reviewing the themes of the classic Western, it becomes clear that those who defend the Western, cannot possibly defend it from the viewpoint of classical liberalism, but only from a 20th century worldview where bourgeois society must subject itself to the authority of gunmen or face oblivion. In the Western, those who remain preoccupied by economic and domestic interests live rather trite lives until they embrace the way of the gun. The real conflict then is between the non-gunfighters of the frontier (who represent the outdated and dangerous notions of an ill-conceived bourgeois society) and the heroic gunfighter, a symbol of a 20th century society much better suited to deal with the harsh realities of the world.

The evolution of the Western in film follows fairly well the evolution of the written literature, so I will use Western films to represent the genre as a whole. The films of six influential directors in particular will provide an insightful sampling of Westerns made since the 1930’s. During the 1940’s and 50’s, as the Western grew to the height of its popularity, the most influential and popular directors of Westerns were John Ford, Anthony Mann, and Howard Hawks. These men would develop the Western film into the iconic genre we know today, and they dominated Western films for decades with their epic, big-budget Westerns. Films like Stagecoach (1939), Winchester ’73 (1950) and Rio Bravo (1957) are considered defining films in the history of the Western, and in these films and others by these directors, the canon of the classic Western took shape.

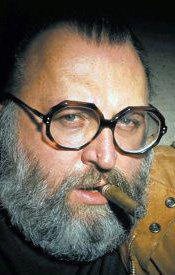

Sergio Leone

Sergio Leone

While Ford, Hawks, and Mann dominated the era of the classic Western, Sergio Leone, Sam Peckinpah, and Clint Eastwood would revolutionize the Western in the 1960’s and 70’s. In fact, before the traditional Western had even disappeared, Leone and Peckinpah would be reworking it and questioning many of the original themes and conclusions. The later Westerns could be critical of the classic Westerns, but the new Westerns, with a few exceptions, never quite abandoned the themes set out from the earliest days of the genre. Indeed, the many made-for TV Westerns being produced today for cable television have more in common with the classic Westerns of decades long past than the revisionist Westerns of the 70’s, 80’s, and 90’s. The fact remains that at the core of almost every Western is a fight against the domestic and liberal values of the 19th century, and this has been true from the very beginning.

The Western and Nostalgic Primitivism

It is significant that while liberalism developed and enjoyed its greatest influence in an industrializing world where international trade, the division of labor, and the urban landscape became increasingly important fixtures of life, the Western would celebrate primitive modes of living while portraying cities and advanced economic systems as an effeminate corruption of the "natural" human condition.

The Western began in the age of "Nostalgic Primitivism" (to use Gaylyn Studlar’s phrase), where novels and early silent films used the new genre of the Western as a means to "redefine the nature of masculine identity in a society increasingly regarded as u2018overcivilised’ and u2018feminised.’" Referring specifically to the Westerns of Douglas Fairbanks, Studlar identifies the Western in these early years as part of a "widespread effort to redefine American male identity in response to perceived threats from modernity."

Perhaps the chief popularizer of this revolt against cultured urban life at the close of the 19th century was Theodore Roosevelt, a privileged Easterner who had convinced himself that his travels in the American West had somehow made him much more masculine than most of his fellow American men. Roosevelt, like countless others at the turn of the century, believed that camping out in the woods was the best way to achieve "character development" in young boys. According to Studlar, "character-builders embraced a nostalgia for a primitive masculine past. The strongest evidence of the past in contemporary life was the instinct-driven u2018savagery’ of boys." Ernest Thompson Seton, head of the Boy Scouts of America, would claim that living the primitive life was an "antidote to u2018city rot’ and the u2018degeneracy’ of modern life."

In Western after Western from the earliest days of the genre to even modern times, the hero is set up as an uncultured man of the frontier who is quite contemptuous of the effeminate and urbanized Easterners who cross his path. Over the course of a typical Western tale, the urban fool must learn the ways of the gun or be destroyed. The representative of complex or ineffective Eastern values has little to contribute to the more pure and primitive order established by the tough men of the West.

The doomed soldiers of Fort Apache: “They’ll keep living as long as the Army lives.”

The doomed soldiers of Fort Apache: “They’ll keep living as long as the Army lives.”

In John Ford’s Fort Apache (1948), this theme is immediately clear as Colonel Thursday arrives in the Arizona desert quickly declaring that he’d much rather be in Europe than the American West. Thursday simply doesn’t understand the ways of the West, and when he refuses to shake hands with a low-ranking cadet, it is apparent that Thursday is far more concerned with the letter of the law practiced in the East than with the more primitive (and presumably just) code of honor that governs the Army on the frontier. Thursday happily works within the restrictions imposed by the civilian government while Kirby York, his frontier-bred number-two, strains under its burden of bureaucracy. At every turn, the Easterners are far less honorable and effective than the frontiersmen who know better. Thursday’s ambition and attachment to Eastern ways eventually brings about his downfall as he leads an ill-fated charge against the Apaches.

This theme is repeated in Rio Grande (1950) as Kirby Yorke’s [he’s "York" in Fort Apache, but "Yorke" in Rio Grande] son must be made to learn the ways of the frontier against the objections of his mother. In Cheyenne Autumn (1964) Ford portrays the frontier cavalry as only guilty of reluctantly following orders when the Eastern bureaucrats hand down orders that lead to the annihilation of the Cheyennes.

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance: The man of letters sits in his apron while the gunfighter makes the streets safe.

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance: The man of letters sits in his apron while the gunfighter makes the streets safe.

This theme is further developed to perfection in Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) where Ransom Stoddard (James Stewart), an Eastern Lawyer and obvious symbol of Eastern civilization is continually harassed by outlaw Liberty Valance. Stoddard is incapable of defending himself, although he thinks he has beaten Valance in a showdown. We learn later that Stoddard had in fact missed and Valance had been killed by Tom Doniphon (John Wayne), a crusty frontiersman. The public does not know this however, and Stoddard is lionized as savior of the town. Soon afterward, the territory becomes a state, Stoddard is made a Senator, and freedom reigns gloriously. Yet, this new gift of civilization was not made possible by the effete Stoddard but by Doniphon who selflessly allows Stewart to take the credit. Doniphon, being a mere humble frontiersman, believes himself unfit for a leadership role in the rapidly civilizing West.

In all of these cases, the film presents the gunfighter — who in Ford’s films, is virtually always a government agent — as the only truly competent defender against threats to the establishment of law and order. In each case where the "simplicity" of the West is victorious over the complexity and corruption of the East, it is with the Eastern interloper attempting to use law and reason to limited avail while the gunfighter functions much more successfully on blind instinct. Stoddard keeps attempting to reason his way to a solution with Valance, but in the end, this proves useless, as the only thing the men of the West understand is brute force.

The impetus behind this fondness for savagery and Primitivism, as Studlar notes, is a distinct reaction against the urban bourgeois life that characterized the 19th century. Referring again to the early Westerns of Fairbanks, Studlar writes

"In his films, without literally becoming a child, Douglas Fairbanks seemed to achieve a change that many American men in routine-driven, sedentary, bureaucratized jobs yearned for. The onerous psychic and physical demands of masculinity could be held in abeyance by a hero who embodied qualities of intensity, vitality, and instinctual liberation which seemed to many, to be increasingly difficult to acquire and retain among the complacency, compromise, and consumerist comfort of modern bourgeois life."

Criticizing modern bourgeois life then becomes a raison d’tre of the Western early on, and the theme of the competent and honest frontiersman against the incompetent and duplicitous Easterner becomes an enduring symbol.

The Bourgeois World

From Marxist historians like Eric Hobsbawm to classical liberal historians like Paul Gottfried, the political liberalism that so dominated the 19th century was so closely tied to the rise of the bourgeois middle class as to be virtually inseparable. As Gottfried describes it in After Liberalism, the old classical liberalism of the 19th century was centered on the values of the rising middle class that glorified the business-oriented private property owner. These middle class liberals valued self-responsibility, a commitment to family, and an acceptance of long-term obligations to both home and the workplace. The "good" man of the 19th century middle class planned for the future with sound savings and investment. He was a part of complex economic and social systems of families, markets, and political institutions, all of which he used to forward bourgeois goals. And, it should be remembered, bourgeois society was a Christian society.

Liberalism dominated politics throughout America and Western Europe where members of the rising bourgeois classes, chafing under the yoke of ancient systems of government privilege and control, set out to strip government of its power. In its place, the bourgeoisie wanted regimes friendly toward free trade, low taxes, large-scale business enterprises and liberty. Perhaps most important of all, they wanted peace. When one is the owner of a major economic enterprise dependent on international trade, war is extremely bad for business. In America, such liberal views of war were exemplified by early American isolationism or the foreign policy views of the Manchester liberals. Fed up with the dynastic wars of the age of absolutism and the persistent mercantilism of every age, the bourgeoisie had grown extremely suspicious of both power and war.

The bourgeoisie were naturally criticized for this. Napoleon scoffed at the British as a nation of shopkeepers, concerned with matters of commerce when they should have been tending to more glorious pursuits such as war. Some Brits theorized that their countrymen, the Manchester liberals, would gladly have accepted military conquest by the French — as long as it produced new business opportunities. In America, liberals who were seen as excessively attached to peace and free trade —Thomas Jefferson, for instance — were denounced as traitors and fools.

As liberalism was the political theory of the bourgeoisie, Victorianism was its social philosophy. The exalted position of domestic and commercial life during the Victorian era in Britain permeated American social structures as well. The family was of exceptional importance, while dignity, restraint, prudence, thrift, temperance and fortitude, were all viewed as important values that provided a solid foundation for the preservation and advancement of Western Civilization.

The gunfighter, whether wandering loner, sheriff, or military man, is very rarely a member of the bourgeoisie. The gunfighter does not own property, he does not have savings or make investments. He does not have a family, and he rarely, if ever, has any use for God at all. In the Western, this figure so hostile to bourgeois sensibilities remains always at the center of the action. There might be a businessman or family patriarch somewhere in the background, but such figures remain more or less as props viewing the action with little more input than the audience sitting in the theatre.

Anthony Mann’s gunfighters in The Man From Laramie (1955), Winchester ’73 (1950), The Naked Spur (1953), and Bend of the River (1952) are all men who emerge from the wilderness, and remain uncomfortable in "civilized" situations. They must always be moving, either to avoid danger, or to escape their pasts, or simply to satisfy a need for a transitory life. As a part of the wilderness itself, they emerge to protect the settlers and society in general from the menaces that exist out in the wilds. Their status as uncivilized and wild is what qualifies them to be effective as defenders of the hapless general public in these films, for if they had actually been an ordinary member of civilized society, they would be incapable of defending themselves and others in the aggressive manner required in Westerns. In Mann’s Westerns especially, the hero is virtually incapable of existing in normal society for he is "near psychotic" as film scholar Paul Willemen describes him. He is motivated by the basest desires such as revenge and greed, yet it is this wildness and lack of control that makes him so valuable to the ordinary people in need of his protection. He might eventually be won over to the cause of the bourgeois settlers, (as in Bend of the River) but this transformation can only take place after the important conflict has been resolved (through violence), and the gunfighter’s services are no longer required. The ultimate message is that suppressing evil and living the bourgeois life are quite incompatible.

In Ford’s films, the hero is less feral, although just as aloof to being attached to the responsibilities of ordinary society. In all four of his cavalry films, Cheyenne Autumn (1964), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), Fort Apache (1948), and Rio Grande (1950), the hero, always a cavalry officer, has virtually no obligations to any family or property, and his affections are reserved strictly for the Army. Only in Rio Grande does the hero, Kirby Yorke, have living family members at all, and even then he is estranged from them and unfamiliar with the responsibilities of family life.

The hero attains his value as an extremely efficient killing machine who is at home only in the wild and is not comfortable filling roles that would normally be associated with an ordinary middle class lifestyle. In these films, the hero is more comfortable in the saddle than in a chair, and more accustomed to sleeping outside than in a bed. He might be tamed for an evening to engage in the niceties of civilization, but he must always return to the wilderness where the important action — the heroic action — takes place.

The gunfighter has attained his status as protector and indestructible man through his many years away from ordinary civilized people, and he therefore carries with him a natural virtue not possessed by the new arrivals in the West. The Primitivist influence on this aspect of the Western is pervasive. Heroism is learned and acted out in the wild, while cowardice and pointless talk take place in the cities and towns and living rooms.

The anti-intellectualism that permeates the Western further serves to solidify the values of Primitivism in its audience. Through the bare-bones efficiency of action employed by the gunfighter, instinctual action and frontier justice can be shown to be morally and practically superior to the more civilized notions of systematic thought and the rule of law. Writing on the consequences of Primitivism’s view of the intellect, Murray Rothbard had this to say:

Civilization is precisely the record by which man has used his reason, to discover the natural laws on which his environment rests, and to use these laws to alter his environment so as to suit and advance his needs and desires. Therefore, worship of the primitive is necessarily corollary to, and based upon, an attack on intellect. It is this deep-seated “anti-intellectualism” that leads these people to proclaim that civilization is “opposed to nature” and [that] the primitive tribes are closer to it. . . And because man is supremely the “rational animal,” as Aristotle put it, this worship of the primitive is a profoundly anti-human doctrine.

This is precisely why the gunfighter so often relies on instinct. In Winchester ’73 for example, Lin does not need to deliberate about killing his own brother. He just "knows" that Dutch was born evil (the only explanation provided for his criminal behavior), and as such is incapable of redemption. Lin cannot realistically attempt to rehabilitate his brother since in the Western, people are either good or evil. In traditional Westerns, good guys never become bad, and bad guys never become good no matter how much they may wish to make a change. The conventions of the Western require absolutely no moral uncertainty or ambiguity, for such things might call into question the absolute righteousness of the final showdown. Such easy dichotomies are essential in the Western. Complex moral or social issues cannot possibly be addressed in an atmosphere where intellectual effort and complexity are viewed with grave suspicion.

Winchester ’73: After fratricide, romance blooms.

Winchester ’73: After fratricide, romance blooms.

Intellectual pursuits are rarely of any value in the cinematic West, and anti-intellectualism manifests itself primarily through the Western’s critique of the Eastern bourgeois lifestyle of the recent arrivals to the West. Lawyers, businessmen, clergy, and others who make their living through the use of words and documents and legal arrangements marginalize themselves through their reliance on such things while the gunfighter succeeds because of his reliance strictly on action. The impotence of white-collar professional types in the West is the primary theme in Ford’s Liberty Valance, but it is common in countless other Westerns where it reinforces a populist and Primitivist view of the West where "eggheads" have precious little to offer society.

Essential to this equation as well is the cheapening of the use of language. Talk is viewed with extensive suspicion, and is usually the central weapon of the villain against the hero. The most reliable plot device to exhibit this axiom of the genre is the positioning of a slick, charismatic villain against a socially-awkward, simply-dressed hero. Hawks uses this device in El Dorado (1966) and Rio Bravo, but Anthony Mann is particularly proficient at this as is shown in Winchester ’73, the Man From Laramie, The Far Country (1954), and Bend of the River in which the villains talk almost constantly with glib tongues while the hero sits in stony silence. The punch line of course, comes when the antagonist’s fondness for talking is revealed as part of his villainy and weakness. Real men, the Western tells us, deal only with actions. Fools and villains, on the other hand, confuse things with talk.

The final lesson to be learned in this is that the virtuous Westerner has no need of finely crafted words and slick reasoning to make his way through the frontier. A contract is unnecessary when a handshake will do, and a group discussion over a proposed plan of action is foolish when the hero can jump into the saddle and accomplish something. It is always better to be silent and strong, as is the impetus behind Nathan Brittles’s famous advice (of dubious value) in She Wore a Yellow Ribbon: "Never apologize, son. It’s a sign of weakness."

Capitalism in the Western

Primitivism is not limited to expounding on the heroic nature of savagery. A recurring theme in the Westerns is a distrust of industrialized societies and complex economic systems. As Tompkins points out, just as language is to be distrusted because of its symbolic nature, money, as a representation of economic value, is also to be distrusted. Contracts, bank notes, and deeds are all symbols of economic value that cannot immediately be understood with the senses, and are therefore suspect. Large businesses in the Western are particularly threatening. Everywhere in the Western, the railroads are a sign of Eastern decadence and corruption. Large ranchers and industrialists commonly attempt to exploit the honest people of the West, and everywhere we look in the Western, private companies are portrayed as vultures preying on the new settlers.

Libertarians and other modern right-wing defenders of the Western point to the fact that the defense of property rights is a common theme in Westerns. On the surface, this is certainly true, but if we look more closely at the conflicts over property common in the Western, the conflict is between two property owners, with one being a large property owner, and the other being small. In the end, the small property owner will win, for it is just assumed that this outcome is somehow more just.

Probably the most well-known case of this is George Stevens’ Shane (1953) in which a number of small farmers move onto land that has been run for years by Ryker, the proprietor of a vast cattle ranch. The film’s central assumption is that the farmers have a right to Ryker’s land for some reason, and when Ryker objects to the farmers’ squatting, he is portrayed as a villain. The film doesn’t provide a convincing explanation as to why exactly Ryker should give up his land to the farmers, yet it is just assumed that since the farmers are small underdogs and Ryker is a big rancher, he must automatically be the bad guy. This same conflict appears in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance in which the big ranchers oppose statehood for the territory because it would break their stranglehold on land in the region. The small ranchers are victorious, though, once flag-waving and democracy are brought to the territory and the fiendish big ranchers are defeated.

Bend of the River: Never trust those greedy businessmen.

Bend of the River: Never trust those greedy businessmen.

In Rio Bravo, after a wealthy land baron’s brother is jailed, the baron hires a gang of killers to overrun the sheriff’s office where the protectors of the honest townsfolk are holed up. El Dorado (a remake of Rio Bravo) naturally employs a very similar plot device. In Anthony Mann’s Westerns, new settlers to the West are constantly in danger of conniving businessmen who seek to exploit and defraud anyone who comes into their territory. How exactly these exploiters manage to stay in business is never explained. Yet, in both The Far Country and Bend of the River, the central threat to the townsfolk is the local large businessman who is responsible for the corruption of law and order, while Hawks’s The Big Sky features an evil "fur company" that attempts to violently crush all competition.

These storylines all follow a basic pattern in which the townsfolk are threatened by an aggressive and evil business interest that seeks to exploit all for its own interests. The only thing standing between these businessmen and their sinister aims is the gunfighter, who is usually a government agent, perhaps a sheriff or a federal marshal. The people beg for deliverance from the exploiters, and justice is served with a few well-placed shots.

She Wore a Yellow Ribbon: Making sure no one’s engaging in any unauthorized buying or selling.

She Wore a Yellow Ribbon: Making sure no one’s engaging in any unauthorized buying or selling.

So yes, the defense of private property is certainly a theme in Westerns, but "property rights" is understood as the crushing of large business enterprises for the good of "the people." In essence, the view of business in the Western is the view one would expect from a genre that took shape during the Progressive Era, and reached its greatest popularity among a population that overwhelmingly supported the New Deal. Everywhere, large business interests are out to crush small business interests, and must be neutralized. The influence of Nostalgic Primitivism is apparent as well since while small, simple one-man operations are looked upon with great fondness in the Western, large enterprises and sophisticated business practices are not to be tolerated.

The Western takes a dim view of the free market in other ways. Stagecoach features a banker stealing the payroll owed to the workers, a particularly insidious act of theft. The banker then proceeds to extol the virtues of the American business class. His hypocrisy is obvious. Winchester ’73, Fort Apache, and She Wore a Yellow Ribbon all feature merchants who engage in the apparently unforgivable act of attempting to trade guns and other goods to the Indians. Indeed, in Fort Apache and Yellow Ribbon, it is shown that a central purpose of the cavalry is to enforce trade embargoes against the Indians. In Yellow Ribbon and Winchester ’73, the merchants are murdered by the very Indians they are trying to do business with. Why the Indians would kill those who supply them with essential goods is certainly not explained, but the message to the audience is clear that such are the wages of trading with the enemy. In The Man From Laramie, it is revealed that the villain plans to sell rifles to the local Indians in an effort to keep the Army away so he can rule the entire countryside with an iron fist. When the hero, Will Lockhart, learns of this, he declares with ferocious disdain that "some people will sell anything to make a profit."

Red River: Rancher Tom Dunson murders an uncooperative employee.

Red River: Rancher Tom Dunson murders an uncooperative employee.

Excluding Ford’s silent Westerns from the 20’s, if we look at the Westerns of Mann, Hawks, and Ford, we find only one film where large-scale capitalists are not portrayed either as villains or as fools. This one exception is Hawks’ Red River (1948) in which Tom Dunson builds a cattle empire through his own efforts, although he acquires the land by killing a rider of the Mexican Don who already owns it. Even Dunson would inevitably enter quasi-villain status as his commitment to drive his cattle from Texas to Kansas slowly turns into violent megalomania, and he begins murdering any employee who expresses doubts about the venture when things begin to go poorly.

Given the Western’s origins, there is nothing surprising about the Western’s anti-capitalist stand against the 19th century and all its factories, corporations, stock markets, and other components of an economically advanced civilization. In the Western, it is alright to do business, but not too much business lest one become corrupted. Contrary to the 19th century bourgeois liberals who saw free trade and markets as a source of enduring prosperity, peace, and cooperation, the Western sees business and trade as a zero-sum game where exploitation is much more likely than cooperation.

The economics of the Western fits quite well with the Primitivist view of modern economics in which advanced economies exploit workers, coerce the public, and rob men and women of their right to live off the fat of the land. This romantic view of subsistence living is economic analysis at its worst, as was pointed out by Murray Rothbard in his critique on the division of labor and Primitivism pointing out that not only is modern industrialization necessary to keep the significant bulk of humanity alive, but that modern civilization offers the best hope for a decent standard of living for most of the human race. Even many Marxist historians agree that the rapidly urbanizing world of the 19th century was marked by substantial and unprecedented improvements in the standard of living for a very large portion of the population. These wages were made possible by increases in productivity that resulted from new economies of scale and major industrial development. The industrial revolution made it possible for the bulk of humanity to rise above the most base levels of subsistence living for the first time. Yet, one certainly wouldn’t learn this from watching Westerns. From its earliest days to the present, the Western has embraced a view of frontier economics where all men live in a state of virtual equality as they work their lands and trade simple goods for simple necessities at the general store.

The Western and Domestic Virtue

While the Western has little patience for the economic complexities of the market and the industrialized world, it is all the more contemptuous of the social and religious life of the Victorian bourgeois world that dominated American culture throughout much of the 19th century. The American middle class of the 19th century, much like the middle class throughout Western Europe, was dominated by bourgeois assumptions about the role of the domestic world in the larger society. The Cult of Domesticity (as it is now known by its critics) was one of the primary characteristics of 19th century bourgeois American culture.

Proper domestic conduct was no small affair. The domestic sphere in the bourgeois world was seen as the fundamental building block of Western civilization. Contemporary defenders of the bourgeoisie from Vienna to San Francisco knew that it was the family home that made civilization function, and it was the institutions associated with the home that had made Western civilization the most free and the most prosperous civilization on Earth. Indeed, the bourgeois home was the symbol of bourgeois liberal society. The liberal movements throughout Europe during the 19th century that attempted (usually unsuccessfully) to restrain the State through constitutions and representative governments were to a large extent executed with the goal of blocking the State from interfering in the domestic and economic pursuits of bourgeois families and individuals.

As the 19th century progressed, family and domestic relationships began to change. As the wealth and size of the middle classes throughout America and Europe continued to grow, a considerable number of ordinary families, for the first time in history, could subsist on the income of a single person working outside the home. This was virtually always the husband, so the wives became the central focus of household governance. "Home economics" as we now know it, became very nearly a science during the 19th century as middle class women spent many hours a day in household management and in budgeting the wages earned by their husbands. In most cases, the wife was exclusively responsible for household management including the physical maintenance of the home, the long-range planning for future capital needs, furniture, utilities, and countless other chores considered absolutely essential to the economic stability of the family.

Especially important was the education of the children in the arts, sciences, and religion. Women were responsible for educating the children, so women attained widespread literacy, and given the requirements of home economics, the wives and mothers were regularly educated in mathematics and basic science as well. For the bourgeoisie, there was no question about what sustained civilization. It was the domestic, literate, and Christian ethic learned in the bourgeois home.

In many ways, homes and churches would become worlds dominated by women. Women attained more and more power in the domestic sphere and in the churches where the middle class women who were fortunate to have discretionary time would devote their resources to tending to the poor and illiterate. Eventually, women would become very active in political movements, whether they were in favor of relieving poverty or abolishing slavery. As the century came to an end, women would be at the forefront of the peace movement against the Spanish-American war and against American entry into the First World War. Women’s groups would march against imperialism, against slavery, against drunkenness, and against anything else they saw as a threat to domestic life.

Today, the Anglo-American version of the bourgeois ideal, Victorianism, is often viewed with disdain and Victorian imagery is used to conjure up thoughts of sexually repressed women and psychologically damaged children living at the mercy of some monstrous patriarch. But those who actually lived in the bourgeois world saw (correctly) that they were witnessing a historical period in which economic prosperity paved the way for women to acquire more wealth and to become better educated than in any previous historical period.

By the time the 19th century gave way to the 20th, it was clear that Primitivism had become attractive to many who had become resentful of the bourgeois life that had so shaped the 19th century. In her essay, West of Everything, Jane Tompkins views the Western as an assault on both the bourgeois world of the 19th century, and on the women who were such an important part of that world. Tompkins’ analysis rests on juxtaposition between the popular literature of the 19th century and that of the 20th. Granted that the Western was the most popular and commercially successful genre of the 20th century, Tompkins looks to the "sentimental" Victorian novels that dominated popular fiction through much of the 19th. The literature of the 19th century, pioneered by female authors like Harriet Beecher Stowe, Susan Warner, Maria Cummins, and others, could not have been more unlike a traditional Western:

In these books (and I’m speaking now of books like Warner’s The Wide Wide World, Stowe’s The Minister’s Wooing, and Cummins’s The Lamplighter) a woman is always the main character, usually a young orphan girl, with several other main characters being women too. Most of the action takes place in private spaces, at home, indoors, in kitchens, parlors, and upstairs chambers. And most of it concerns the interior struggles of the heroine to live up to an ideal of Christian virtue — usually involving uncomplaining submission to painful and difficult circumstances, learning to quell rebellious instincts, and dedicating her life to the service of God through serving others…there’s a great deal of bible reading, praying, hymn singing, and drinking of tea. Emotions other than anger are expressed freely and openly. Often, there are long, drawn-out death scenes in which a saintly woman dies a natural death at home. Culturally and politically, the effect of these novels is to establish women at the center of the world’s most important work (saving souls) and to assert that in the end spiritual power is always superior to worldly might.

Tompkins continues:

The elements of the typical Western plot arrange themselves in stark opposition to this pattern, not just vaguely and generally, but point for point. First of all, in Westerns (which are generally written by men), the main character is always a full-grown adult male, and almost all of the other characters are men. The action takes place either outdoors —on the prairie, on the main street — or in public places — the saloon, the sheriff’s office, the barber shop, the livery stable. The action concerns physical struggles between the hero and a rival or rivals, and culminates in a fight to the death with guns. In the course of these struggles the hero frequently forms a bond with another man — sometimes his rival, more often a comrade — a bond that is more important than any relationship he has with a woman… There is very little expression of emotions. The hero is a man of few words and expresses himself through physical action — usually fighting. And when death occurs it is never at home in bed but always sudden death, usually murder.

It is surely not a coincidence that 19th century American society, which the Primitivists would criticize as too civilized, would relish Victorian novels while the Western, a genre dominated by violence, aggression, and war would come to be loved by so many during a century notable primarily for bloodshed on an unprecedented scale.

Novels like those written by Stowe, Warner, and Cummins were immensely popular during the 19th century, and not just among women. The themes of Christian virtue and endurance of evil never failed to please. To further illustrate this, Tompkins points to Charles Sheldon’s 1896 book In His Steps which chronicles the evolution of a congregation as it attempts to live a radically charitable Christian lifestyle. This book was wildly popular, was translated in 21 languages, and sold many hundreds of thousands of copies. In this same period, books such as Ben Hur and Quo Vadis featured heroes who do not triumph by killing their adversaries, but by meekly enduring a series of trials, and ultimately, persevering in their faith in God.

Tompkins’ conclusion is that the Western, being so hostile to Christianity and to domestic virtue, is at its most basic level designed to negate the role of women in American society. She undoubtedly has a point here, but she misses the larger point. Her observations on how the Western "jettisons" most everything dear to middle class Americans during the 19th century (i.e., domestic Christian values) take us closer to the truth. The non-essential roles that women play in the Western are certainly emphasized in the films, but the women are not just women in the Western, they are also representatives of bourgeois society. As the Nostalgic Primitivists made clear with their hatred of industrialized society and with their utopian schemes for achieving manhood in a mud hole, the real loathing being propagated by the Western is not necessarily for women, but for the urban, industrial, bourgeois world that had so radically changed Western Civilization. The Primitivists may have been (and probably were) misogynists, but their real interest was in subduing not women, but the larger society they represented.

Women in the Western

In many Westerns, women serve a similar function to the effete males of the East. They lack an understanding of the ways of the West, and they fail to grasp the monumental importance of the work being performed by the gunfighter. In Rio Grande, for instance, Yorke’s estranged wife is told by her son that Yorke is a "great soldier," and she responds that "what makes soldiers great is hateful to me." Yet, we’re not supposed to sympathize with Kathleen when she makes this statement. By the end of the film, she modifies her value system to match his, and Yorke remains unchanged. We are led to conclude that she simply doesn’t understand the sacrifices that must be made to bestow the blessings of modern government on the frontier. In She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, the hero’s wife is long dead, so the hero remains as free to act as Red River’s Tom Dunson who deserts his fiancée to build his ranch. Dunson then stumbles upon a young orphan in the wilderness. The subsequent adoption of the orphan allows Dunson to acquire an heir without the inconvenience of having sex with a woman. It is also helpful in providing an excuse to avoid having any themes of domestic life in the film, even though the film is ostensibly about a family dynasty.

The Searchers: When a woman talks, no one listens.

The Searchers: When a woman talks, no one listens.

Often, women are just obstacles to be overcome. In Fred Zinnemann’s High Noon (1952) Mrs. Kane allies herself with the cowardly townsfolk and tries to convince Marshal Kane to leave town before the villains arrive. Similarly, in The Searchers (1956), after a woman and her older daughter have been raped and murdered by Indians, and a second daughter kidnapped, Ethan Edwards, the hero, is told by an older woman to not encourage the young men to waste their lives in vengeance. Edwards ignores her. He then leads the men on a multi-year hate-fueled spree across the desert.

In other films, women explicitly represent civilization. In My Darling Clementine (1946), Clementine attempts romantic attachment to Wyatt Earp, yet Earp rejects her so he can ride off to a showdown with the Clantons. He eventually leaves Tombstone altogether (without her) so as not to be ruined by the civilized ways of the growing town. In The Naked Spur, it is the woman who convinces the hero to give up his bounty hunting and take up an ordinary life. The hero’s submission to the heroine’s domestic urgings is seen more as a defeat and surrender than as anything heroic. In all the Westerns of Mann, Ford, and Hawks, it is women who are used to express ideas about culture, civilization, religion, and family. More often than not, though, such ideas are completely irrelevant to the resolution of the central conflict which is always resolved through a gunfight. The woman’s talk can be safely ignored. The women encourage compromise, nonviolence, and "settling down," yet the life of the gunfighter is incompatible with all of these things.

The gunfighter is often shunned by the ignorant and puritanical townsfolk. As film scholar David Lusted has noted, the gunfighter takes on the persona of the "troubled innocent," a man whose great value to the community is either shunned or ignored by the community, specifically the women. Anthony Mann was particularly proficient at creating this type of hero, as with his characters Mork Hickman in The Tin Star, and Will Lockhart in The Man from Laramie. Ford employed this from time to time as with Earp in My Darling Clementine and the Ringo Kid in Stagecoach, although most of his gunfighters were professional government agents.

God and Religion in the Western

Stagecoach: Fleeing the shrewish women back in town.

Stagecoach: Fleeing the shrewish women back in town.

While women are symbols of domesticity in the Western, they also represent religion. As Stagecoach opens, Dallas, the clichéd whore with a heart of gold is being run out of town by the shrewish women who have created a frontier version of the League of Decency. Dallas’ woes are increased by the prejudices of the bourgeois passengers on the stagecoach. Fortunately, a few hours in a stagecoach together shows them all the errors of their ways. In Mann’s The Far Country, the women (most of them saloon girls) talk about building churches at some time in the distant future, implying that when churches arrive, the process of settling the frontier will have been complete. Westerns in general are dotted with occasional references to God, usually made by women, at which point the gunfighter is reliably shown to be made thoroughly uncomfortable by the whole situation.

Christianity in the 19th century was hardly such a marginal and infrequent topic of conversation. As Tompkins has shown, the popular literature of Victorian America was steeped in Christianity. The Victorian world was a Christian world, and the bourgeois families that lived in it identified themselves as Christian and subscribed to a Christian worldview. Christianity was prominent in their literature, in their education, and in their politics. We know that the people who settled the West carried their Christianity with them. Catholic and Protestant missionaries crisscrossed the frontier, and churches sprang up wherever new towns were founded. In spite of all of this however, the Western either ridicules or ignores religion as an important part of the story of the West.

Gunfighters are never religious men. Engaged in the primitive world of the kill-or-be-killed frontier, the gunfighter has no time for such immaterial pursuits. He knows only one thing — physical survival — and no amount of praying is ever going to do him much good. In fact, the gunfighter himself serves as a sort of divinity, doling out death and vengeance without the slightest thought that his judgments might be flawed or that he might be gunning down the wrong man. The gunfighter is always right (a byproduct of the anti-intellectualism in the Western) and he always wins. He is simultaneously omniscient and omnipotent. He doesn’t need God, for he is a god — impervious to the dangers and trials that would destroy a less able man.

This aspect of Westerns is closely related to the anti-intellectualism of the genre since, as noted above, the Western relies on a moral structure of simplistic dichotomies between good and evil. Later Westerns are notable for their moral ambiguity, but the traditional Westerns create a world where the gunfighter (the elect) destroys the villain (the damned) with the help of the gunfighter’s infallible instincts. When it comes to one’s status as a member of the elect or the damned, the characters in Westerns are quite lacking in free will since free will would imply an ability to repent of one’s evil ways or, conversely, to fall from grace. That fact that characters in Westerns virtually never do either illustrates the Western’s need to dispense with anything that might complicate the moral landscape.

Since eternal souls don’t matter in Westerns, the concepts of the elect and damned retain only a worldly status, but they are nevertheless extremely important in providing justification for the dependence on violence so central to Westerns. Unlike the Victorian novel where saving souls is an important consideration, the Western, through omission, denies the existence of a spiritual world, existing only in the physical world where physical elimination of the enemy is the only goal worth considering. Salvation is important in the Western, but it is a strictly physical salvation dependent on "redemptive violence" through which the simple moral order is rescued through the violent intervention of the gunfighter.

Religiosity is occasionally exhibited by gunfighters, but when it is, it is shown in a quite terse and dismissive fashion. Red River’s Tom Dunson makes a mockery of Christian values when on several occasions he guns men down for petty offenses, buries them, and stiffly recites some scripture ("The Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away") before getting on with the day’s chores. Ethan Edwards in The Searchers can’t even be bothered to endure the funeral of his own relatives when he’d rather be on a horse getting important things done.

The afterlife is apparently a source of great confusion in Westerns. Following the bloodbath incompetently engineered by Colonel Thursday, York (to the strains of the Battle Hymn of the Republic) declares that the dead soldiers "aren’t forgotten because they haven’t died. They’re living right out there and they’ll keep on living as long as the army lives." Piles of corpses don’t occasion one to mention God — just the Army. In a genre so replete with death, one might think that the characters might think from time to time about man’s ultimate fate. Such thoughts never occur to a gunfighter.

For the gunfighter, what matters is physical survival, and the central concern must be physical life and physical death. The biblical contentions that "to die is gain" or that it is better to endure an evil than to commit one, are absolutely meaningless in the Western. The Christian ethic is all the more ridiculous since in the Christian worldview, death may have to be accepted for the sake of defending a larger principle, but in the Western, death is always defeat. God, therefore, is persona non grata, and the only things that can be trusted in the Western are a ready gun, a steady horse, and a fast draw. The gunfighter may ride for the greater glory of his countrymen and the United States of America, but he most certainly isn’t riding for God.

Just as Ford used caricatures of puritanical women as a symbol of religion, Westerns can also use churches as general symbols of the surrounding bourgeois society. High Noon uses this device as a means to exhibit the town’s cowardice and hypocrisy. Looking for help against the outlaws, Kane is determined to gather support from the local church. He interrupts the Sunday service as the minister reads scripture. While he urgently seeks help, Kane is curtly reminded that he didn’t “see fit” to be married in that church: “What could be so important to bring you here now?” Kane simply replies: “I need help.” He admits that he isn’t “a church-going man,” and that he wasn’t married there — because his wife is a Quaker. “But I came here for help, because there are people here.” The cruel and oblivious congregation offers no help.

There are only so many scenes that one can cite here to illustrate the Western’s dim view of Christianity because the deafening silence with which the Western treats Christianity so permeates the genre. Neither Mann nor Ford nor Hawks ever see fit to include Christianity as anything other than a minor consideration of those who tend to be an irritant to the hero gunfighter, further illustrating the Western’s drastic and lasting departure from the popular entertainment of the 19th century.

The Gunfighter Against the People

As a final illustration on the Western’s dim view of American bourgeois society, Ford’s Two Rode Together offers a well-rounded example. It is one of Ford’s lesser known films, but in it we see the development of many of the anti-bourgeois themes that permeate his films. The film is laden with stereotypical portrayals of gullible Eastern settlers, cynical businessmen, and spiteful, gossiping women.

The film opens with Army officer Jim Gary (Richard Widmark) recruiting Guthrie McCabe to help him track down abducted whites living among the Indians. McCabe is a corrupt and jaded lawman, but he agrees to the job after he secures some attractive benefits for himself. At the settlers’ camp, McCabe is accosted by numerous parents still looking for their children who had been abducted by the Comanches years earlier. The chance of finding the children (now adults) and determining which ones belong to which parent is extremely low. The parents are desperate and pathetic, although not necessarily for the right reasons, and sheriff McCabe shines as a paragon of virtue next to the self-important businessman Mr. Harry J. Wringel who cynically explains that all he needs is any white male he can pass off to his wife as their son.

Two Rode Together: The settlers lynch an “Indian.”

Two Rode Together: The settlers lynch an “Indian.”

Eventually, McCabe manages to bring back two captives from the Comanche camp: one white male and one Mexican woman. The white male, a teenage boy, now thinks of himself as a Comanche and no longer speaks English. McCabe encourages compassion for the young man, but the settlers can’t be bothered to do much other than lock him up. The latent racism of the settlers prevents them from seeing him as one of their own, and he is treated worse by the settlers than he was ever treated by the Comanches. The young man turns out to be the brother of one of the settlers, but before his sister can figure this out, he kills one of his captors and is lynched by a vicious mob of settlers. Later, the other former captive, the Mexican woman Elena, is ostracized by the settler women of the settlement for being an Indian’s concubine. The settler women believe that Elena should have killed herself rather than submit to such an unseemly fate. In the end, McCabe lectures the townspeople on their lack of tolerance, and he rides out of the settlement with Elena.

So ends another Western, with naïve, selfish, and hypocritical townsfolk, being shown the virtuous path by the sheriff, the military man, or some other gunfighter who can rise above the insipid prejudices and dysfunctional bourgeois ways of the people he is selflessly serving. Two Rode Together is one of Ford’s last Westerns and like The Man who Shot Liberty Valance, and Cheyenne Autumn, Two Rode together is a more melancholy and pessimistic film that his earlier efforts. Yet, the anti-bourgeois attitude is very much in line with most Westerns of the 1950’s. The settler-gunfighter dynamic in Two Rode Together is extremely similar (as we shall see below) to that found in The Tin Star (1957) and High Noon, where the gunfighter educates the settlers on how to abide by their own professed values. Two Rode Together, like so many of its contemporaries, manages to posit a scathing critique of Eastern bourgeois society while setting up the gunfighter in a position of moral ascendancy who in his primitive state, is nonetheless more civilized than the hypocrites who claim to be civilizing the frontier.

The Transformation of the Western

By the mid-1960’s the Western had changed. The old view of the settlement of the frontier as triumphant progress in the face of savagery had broken down. While the Western had never been completely static, big-budget Westerns of the 1940’s and 50’s had generally followed reliable formulas that we now easily recognize as being part of the tradition of classic Westerns.

Part of the reason for the change was the fact that the directors who had dominated the Westerns for two decades were reaching the end of their careers. In 1964, John Ford released his last Western, Cheyenne Autumn. Howard Hawks continued to make Westerns until 1971 although both Westerns produced after 1959’s Rio Bravo followed identical traditional Western plot formulas. Anthony Mann directed no Westerns after 1960.

Every scholar of the Western has a theory about the genre’s evolution from its classic form to the darker and more ambivalent modern form. The Westerns of the post-classic age would prove to be more pessimistic, more graphic, and far less likely to portray the frontier as a place of rejuvenation. A common explanation for this change is that the Vietnam War and the crisis of legitimacy that the United States suffered during the 1960’s and 70’s fueled a breakdown in the traditional mythology of the West. Perhaps it was the assassination of Kennedy or the Age of Aquarius or Watergate, but one thing was sure, the image of the American gunfighter as harbinger of civilization in a wild land no longer had the same moral authority it once had.

It had been 6 decades since the first Western, The Virginian, had spawned a new genre, and regardless of the cause for its decline, the classic Western no longer seemed to have much to say that the American audience wished to hear. Consequently, the new directors who came on the scene began to rework the Western in new and inventive ways. By 1965, Sergio Leone and Sam Peckinpah had created new Westerns with much different visions that lacked the triumphant militarism of the traditional Westerns.

The Rise and Decline of the State in the Western

When comparing the classic Westerns with the late Westerns, what becomes most immediately obvious is the decline in the prestige of government institutions. The fact that late Westerns have a largely negative view of the State is not in dispute, although the causes for this are debated. To see this, we do not need to look much further than the portrayal of gunfighters as lawmen in Westerns.

In the classic Western, The gunfighter is very often a government agent of some kind. Cavalry officers, federal marshals and local sheriffs were all popular gunfighter heroes. As noted above, all of John Ford’s non-silent Westerns feature government agents as the protagonists with only two exceptions. In the two exceptions, Stagecoach and The Searchers, John Wayne plays a charming outlaw and an unreconstructed Confederate soldier respectively. At the climax of each film, the United States cavalry is nonetheless key to the resolution as it provides essential support in suppressing Indians that pose a threat to the protagonists. Ethan Edwards, The Searchers’ ex-Confederate main character, who contemplates murdering his abducted niece because she has gone native, is the least heroic of Ford’s protagonists. Ford purposely portrays him as a rather mentally-imbalanced racist motivated primarily by a lust for revenge. He’s nevertheless shown to be rather lovable — and certainly indispensable — by the time the final credits roll.

This portrayal is particularly interesting in light of Ford’s treatment of former Confederates throughout his films. Ford’s nationalism comes through in his repeated return to the theme of reunification between North and South. In his cavalry Westerns, it is common to find a scene in which a confederate veteran who has joined the U.S. Cavalry following the war, is killed by Indians. The other soldiers —all Northerners — gather around to commemorate the Confederate’s passing as the soundtrack plays a few bars of Dixie. The point of course, is to show the valor in Southerners fighting for the Union and to illustrate the rise of American unity since the war with Northerner joining Southerner in the fight against the savages on the frontier. Anthony Mann employs a similar device in Winchester ’73 when Lin helps a group of Union cavalry soldiers fend off a band of Indians. The commanding officer declares "I wish I had you with me at Bull Run," with Lin declaring that he had been at Bull Run, but on the Confederate side. The two former enemies shake hands and bond over a pile of nearby Indian corpses.

Rio Bravo: A tin star can make all the difference.

Rio Bravo: A tin star can make all the difference.

In addition to delivering messages about national unity, the classic Western often goes to great pains to ensure that the violence employed by the gunfighter is sanctioned by the community at large. An often seen exchange in classic Westerns is a scene in which the good guys are all deputized by the sheriff or the marshal right before the final showdown. This change in legal status for all the heroes involved naturally supplies legitimacy and legal immunity to the gunfighters as they prepare to gun down their enemies. Howard Hawks’s Rio Bravo and El Dorado are particularly notable for the attention they pay to the issue of legitimate and illegitimate power. In both films, the sheriff collects a band of scrappy allies to defend the town against the villainous ranchers and outlaws beyond the edge of town. The close-knit band of deputies combs the town for outlaws and enjoys the support of various townsfolk in the process. When it comes to the showdown, however, the sheriff and his deputies are isolated by their elevated status as professional lawmen, and they must protect themselves until additional official law enforcement personnel can arrive from far off federal installations. This power of legitimacy is conferred on select men by the sheriff himself, who, we are shown, also confers the approval of the entire community.

Gunfighters might also receive legitimacy through public acclamation. In The Far Country, it is significant that when the public demands that Jeff Webster (James Stewart) confront the corrupt sheriff from the neighboring town (he’s allied with some villainous business interests), it is not suggested that Jeff confront the sheriff as a private citizen. First, he must accept public election as the town’s legitimate law enforcement chief. Only then may he then pursue a showdown. The film uses this as an opportunity to compare private, selfish interests (such as tending to one’s private property), with serving the common good as a government agent. At first, Jeff is inclined to mind his own business and work his claim. The moral repugnance of such a position is belabored repeatedly in the film until Jeff finally recants and accepts responsibility as a public servant, sending the message that bad things happen because good men aren’t willing to run for office.

The Tin Star: The enlightened sheriff vs. the backward townspeople.

The Tin Star: The enlightened sheriff vs. the backward townspeople.

While public acclamation is good when the sheriff-to-be is a good guy, it’s necessary to keep a tight lid on power when undesirables might end up in power. In Mann’s The Tin Star, Anthony Perkins plays Ben Owens, an inexperienced sheriff who takes charge only after his father, the previous sheriff, has been killed in the line of duty. The sheriff is tormented from time to time by the town agitator Bart Bogardus who is quite convinced that he could do a better job as sheriff. Fortunately for Owens, Morg Hickman (Henry Fonda) rides into town, reveals that he is a former sheriff himself and agrees to teach Owens how to deal with agitators like Bogardus. Owens learns from Hickman that "If the Sheriff doesn’t crack down on the first man who disobeys him, his posse turns into a mob."

Mob rule is a big problem for Owens since Bogardus is always inciting the townspeople to rebel. Much of this stems from Bogardus’s militant racism as is exposed when he refuses to be disarmed after shooting a half-breed Indian: "No sheriff’s gonna disarm no white man for shootin’ a mangy Indian. What are ya, an Injun lover?" The townspeople in The Tin Star are putty in the hands of whoever is most successful at bullying them. So, Owens learns to bully them. If Bogardus, the racist small businessman is allowed to retain control of the mob, then chaos will reign. But, if the Sheriff takes charge and "cracks down" on those who disobey them, order will be restored. The sheriff eventually has to face down his own town as they attempt to lynch his prisoners. Bogardus is reined in, mob justice is avoided, and goodness reigns. Film historian John Lenihan has pointed out that The Tin Star draws heavily on High Noon which also features a sheriff who must confront the ignorant and cowardly people of his own town. The Tin Star however, goes a step further in saying that the best frontier towns are those where the sheriff keeps the citizenry on the straight and narrow with a fast draw and a big shotgun. Outlaws aren’t the problem. It’s the entire population that’s the problem, and only a mild police state will keep the mob in line.

Such depictions of a benevolent order secured by the quick draw of the gunfighter would grow increasingly rare as the 1960’s progressed. As with Morg Hickman in The Tin Star, the gunfighter of the traditional Western eventually provides his services with benevolence and compassion. They might show reluctance at first, but in the end they always chose to defend the community in need, sometimes even at potentially great cost to self.

The Westerns of Peckinpah, Leone, and Eastwood, on the other hand, would feature gunfighters who held no such feelings of good will. Leone’s stock character, The Man with No Name, played by Eastwood in three films, is a thoroughly self-interested loner who only for very brief moments expresses much interest in anything other than private profit. Peckinpah’s protagonists can be actively menacing. His film Major Dundee (1965), for example, is a cavalry film where the cavalry is led by a nearly mad Union commander, Amos Dundee, who commonly abuses his own men, invades Mexico against orders, picks a fight with the occupying French forces, and partakes in not one, but two bloodbaths as the film draws to a close. In Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973), Pat, newly appointed sheriff, betrays his old friend Billy and guns him down as a service to the New Mexico territorial government. In both cases, the cavalryman and the sheriff, traditionally heroic characters in Westerns are suddenly murderous villains sowing discord wherever they go.

Sergio Leone’s Westerns rarely feature any government agents as prominent characters at all. In general, such agents in Leone’s Westerns are either irrelevant or corrupt as in Once Upon a Time in the West (1968) and The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966). Union soldiers in The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly are particularly monstrous, and the boys in blue prove to be the most snarling, violent, and corrupt people on the frontier. The one Union soldier with a conscience can only manage to face the absurdity of it all by maintaining a perpetual state of drunkenness. This is all part of the film’s profoundly critical view of the State in wartime. Taking place against the backdrop of the New Mexico theatre of the American Civil War, Leone paints the war as a pointless sideshow to the much more interesting and reasonable business of finding buried gold on the frontier. The greed of the protagonists appears quite sane and even charming against the senseless carnage of the war that surrounds them. "Blondie" (Clint Eastwood) even offers a puff on his cigar to a dying confederate soldier in a poignant scene displaying the mercy of the outlaw contrasted against the brutality of war.

The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly: Blondie contemplates the absurdity of war.

The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly: Blondie contemplates the absurdity of war.

A decade later, Clint Eastwood’s own The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976), drawing upon the many films about Jesse James, would feature the exploits of an unreconstructed Confederate guerilla who heads West to escape the disgraceful United States cavalry. In the end, he guns down a detachment of the United States Army with the help of a little old lady and her settler family from Kansas. In Unforgiven (1992), the sheriff, Little Bill, beats a man within an inch of his life for carrying firearms into town.

While some classic Westerns would feature crooked lawmen, such portrayals were never a commentary on power itself. In a classic Western, the problem of a bad lawman is usually solved by the intervention of a good lawman, while in the late Westerns power itself is what makes the bad man bad.

The Persistence of Traditional Elements

The Outlaw Josey Wales: Unreconstructed Confederate guerilla.

The Outlaw Josey Wales: Unreconstructed Confederate guerilla.

We cannot assume that negative portrayals of government in Westerns necessarily mean a rehabilitation of the image of bourgeois society in the Western. The Outlaw Josey Wales is quite an exception in its magnanimous view of middle-class Kansas settlers who form a close bond with Josey as they build a homestead in the wilderness.

An anti-capitalist bias is obvious in Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (1969) for example, when in the opening scenes, it is established that the outlaws’ primary foes are the local railroad conglomerate. The tyrannical and dishonorable railroad men ("We represent the law," they tell us) are contrasted with the honorable killers of the Wild Bunch itself who hold to a code of outlaw honor. The railroad company further makes its monstrous nature all the more clear when its hired gunmen open fire on the Wild Bunch even though a Temperance League parade has wandered into the crosshairs. The resulting bloodbath and the images of bodies of men women and children strewn about Main Street serve to further elevate the outlaws above the wicked railroad.

The Wild Bunch: Killers fresh from the whorehouse.

The Wild Bunch: Killers fresh from the whorehouse.

Nameless, faceless business interests are in collusion with the territorial government of New Mexico in Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid. Their primary motivation for ensuring that Garrett rid them of the Kid is that the Kid has become a thorn in the side of the large ranchers who are attempting to consolidate their power in the region. Garrett thinks he’s his own man, but in the end, it’s revealed that he has not escaped the corrupting influence of corporate America. A man with no name appears in Eastwood’s High Plains Drifter (1973) to avenge the murder of the late sheriff who had discovered that the corporation that rules the town with an iron fist is engaged in illegal mining activities. Naturally, the company will murder to protect its profits. Pale Rider (1985), a loose remake of Shane, pits small-time miners against large-scale miners with the large mining interests eventually resorting to hiring corrupt marshals to force the small miners off their property.