The mistake is one which was exposed in advance by Montesquieu: "As it is a feature of democracies that to all appearance the people does almost exactly as it wishes, men have supposed that democratic governments were the abiding-place of liberty: they confused the power of the people with the liberty of the people." This confusion of thought is at the root of modern despotism.

~ Bertrand de Jouvenel, On Power

The Scandinavian monarchs over the years have become more like hereditary presidents of their welfare states than kings.

~ Robert T. Elson, Life Magazine, April 6, 1964

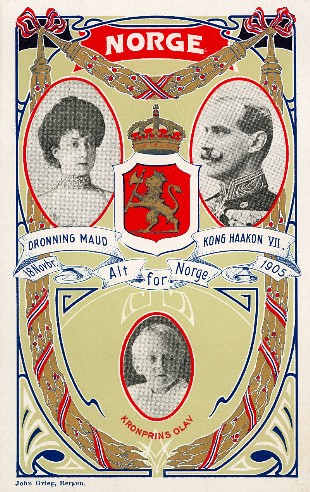

One hundred years ago today Haakon VII was crowned and anointed King of Norway. This not only marks the centenary of the last Scandinavian coronation. It also in a way marks a hundred years since the "coronation" of the work of 1905, which included parting with Sweden and basically the completion of parting with the old monarchical order. This is a remarkable paradox. A coronation marks the dawn of the democratic age.

I wrote about the democratic transition in Norway in a couple of articles about a year ago; one with a wider historical perspective and another concentrating more on Oscar II — in a long and short [LRC] version.

It was the Danish Prince Carl who was made King of Norway as a part of the events of 1905. However, King Oscar II was offered the throne of Norway for a prince of his house, provided that such a prince renounced his rights to the throne of Sweden. This was a tactical move partly to make the coup or revolution look less revolutionary to the outside world, and partly to ease the conservatives. The Norwegian coup-makers had no wish for a king from the House of Bernadotte. The Swedish Prince Carl was the most probable candidate for the throne from the House of Bernadotte. According to historian Roy Andersen the Swedish Prince Carl told Norwegian representatives that he had no interest in being a "marionette troll" at the palace in Christiania. This expression is a much better description of the kind of monarch Norway has had since 1905 than "constitutional monarch."

The Norwegian Parliament moved to depose Oscar II as King of Norway basically because he asserted his right to say no to what democratically elected politicians had moved. If we go beyond the formal technicalities, this is the issue. The declaration of June 7, 1905 from the Norwegian Parliament is a piece of exquisite art of phrasing. It does not mention the denial of royal sanction, which was never written into the official records of the Council of State as it was never countersigned. The parliamentary declaration is concerned with the King’s constitutional duty of providing the country with a Cabinet. It claims the King deposed himself by not providing the country with a Cabinet. It was based on a document from 1847, i.e., from before parliamentarism, that Cabinet secretaries had the right to resign instead of countersigning a royal act.

There are Norwegian scholars who believe the act of June 7, 1905 was not constitutionally in order, but they excuse it because it was democratically endorsed or secured democracy. They especially refer to the referendum of August 13, 1905, in which only 184 — or 0.05 % — said nay to the "union dissolution that had taken place." Other scholars say the Parliament’s act of June 7, 1905 was constitutionally in order. Professor of law Ola Mestad bases his view on the fact that the declaration did not touch the issue of royal veto, but only the right of the Cabinet secretaries to resign and the King’s duty to hold a Cabinet. These factors supposedly make the Parliament’s act constitutionally in order. Lawyer Cecilie Schjatvet has claimed that the union was dissolved both de facto and de jure both constitutionally and when it comes to international law on June 7, 1905. She bases this theory on a presumption that the Swedish state cannot be considered absolute. One could wonder what Ms. Schjatvet thinks of the absolute power of the Norwegian Parliament.

It can easily be imagined what outrage there would be if the King were to declare that the Parliament had deposed itself because, as the King sees it, it has failed to fulfill some constitutional duty.

Christopher Bruun, a priest, wrote a pamphlet to the Norwegian people in 1905. No Norwegian publisher would print it. He had to go to Copenhagen to get it printed. The pamphlet has some wisdom to offer those who are overwhelmed with how well the coup d’état was implemented:

Wrongdoing does not cease being wrongdoing if it is exercised in the nicest forms and with the greatest skill.

It has also been claimed that since Crown Prince Regent Gustaf was warned of the Cabinet laying down their offices if the Act of Consulates was not sanctioned, and since the King and Crown Prince were quite passive during the crisis, the events of May and June of 1905 cannot be labeled a revolution.

A crime is still a crime if it is defended with the most perfectly constructed — and in themselves irreproachable — phrases in court. A crime is still a crime if warning is given of its being committed. Such a crime is still a crime if such warnings do not result in precautions being taken. Before the terrorist attack against the American Embassy in Nairobi in 1998 warnings were reportedly given, and these warnings were reportedly not taken seriously. That does not make the attack any less a crime.

A murder is still a crime if the popular majority approves of it. As Christopher Bruun’s pamphlet tells us:

And the wrong we have exercised does certainly not get better if the entire people learn to shout: it is not we who have done wrong, it is the King.

On the Contrary. That the people learn to turn moral concepts upside down is amongst the worst sides of the issue.

There are a lot of people who walk about with an unclear feeling that when the people or its majority agree on something, it must also be right. Perhaps they do not say it, but it is a part of their mindset. The majority does have the might in many ways to legalize what was formerly illegal. So it must then also have the ability to make wrong right.

And then we have the confusion of moral concepts going like an epidemic.

The fairy tale style story of the harmonious peacefully agreeing people of the August 13 referendum is probably quite widespread. Norwegians deplore similar referendum and election results in countries "with which we do not want to be compared." Professor of history Nils Ivar Agøy, amongst others, has made an honorable attempt at destroying this fairy tale view and myth. Dr. Agøy tells us that the August referendum was set up so that there could not be a shadow of a doubt as to whether the Parliament’s act of June 7 was final and legitimate.

If one did not believe that the Parliament’s act to depose the King and dissolve the union was legally, constitutionally, or otherwise in order, one could not take part in the referendum. As Agøy notes:

[B]y voting at all they accepted that [the dissolution of the union] had "taken place" (the question was a good example of the "have you stopped beating your wife?" type).

The referendum was about discipline, propaganda, angry mobs attacking those few who dared show dissent, and the likes. August 13, 1905 was a Sunday. The referendum largely had its polls in churches. Polling stations were decorated with propaganda for yea to the dissolution. Churches were decorated with Norwegian flags. Typically, a service was held where the parish was told that it was God’s will that the union was to be dissolved. Then the parish went to the polls.

According to Agøy the August referendum is no measure of popular agreement with the act of June 7. He notes:

We do also have many testimonies that people who up to June 7 wished to preserve the union voted yea August 13. This was not necessarily because they had altered their views, but rather because voting nay could not serve any good. It would not bring the union back, but it could make the situation worse for the country in August.

It should be added that probably a considerable amount of men voted yea due to pressure. Agøy notes on the 184 nay voters:

[T]he sources suggest that not a few of them [the nay voters] voted as they did because they took their oaths to Constitution and King more seriously than others, i.e., something concerning the revolutionary sides of the act of June 7, but not the view of the union as such.

We can discuss the issue of might versus right in constitutional history a lot. People tell me it is interesting, but not very relevant for our time. This side won, that side lost. Which side was constitutionally in the right is interesting, but the important thing is which side won, because politics is about might, and the actual outcome is what we are living with today. That is exactly the problem. We have to live with it. We can put all constitutional considerations aside. The fact remains that the limited and mixed governments of the 19th century were far friendlier towards liberty than today’s mass democracies. The Norwegian events of 1905 are a defeat for the concept of limited government and limited parliamentary power.

It is a common claim that 1905 marks the end of the transition to constitutionalism, i.e., that constitutionalism was not fully implemented before the end of Bernadotte rule in Norway. This is true if constitutionalism denotes that the King is completely subject to politicians, and basically cannot interfere in politics. I.e., it is true if the concept denotes a system where the King is basically powerless and at the complete mercy of Parliament, in that Parliament for instance may redefine the monarchy totally, e.g., by redefining how the throne is inherited. It may even abolish the monarchy completely if the royal office or family does not "behave" or loses popularity in the opinion polls. It is not true if constitutionalism denotes a system where the government is limited by a constitution. Nor is it true if constitutionalism denotes a system where the constitution is abided by. Today politicians basically define and redefine the Constitution at will. If constitutionalism denotes a government "of laws, not of men," our history since 1905 is definitely not a history of constitutionalism.

It is a common claim that 1905 marks the end of the transition to constitutionalism, i.e., that constitutionalism was not fully implemented before the end of Bernadotte rule in Norway. This is true if constitutionalism denotes that the King is completely subject to politicians, and basically cannot interfere in politics. I.e., it is true if the concept denotes a system where the King is basically powerless and at the complete mercy of Parliament, in that Parliament for instance may redefine the monarchy totally, e.g., by redefining how the throne is inherited. It may even abolish the monarchy completely if the royal office or family does not "behave" or loses popularity in the opinion polls. It is not true if constitutionalism denotes a system where the government is limited by a constitution. Nor is it true if constitutionalism denotes a system where the constitution is abided by. Today politicians basically define and redefine the Constitution at will. If constitutionalism denotes a government "of laws, not of men," our history since 1905 is definitely not a history of constitutionalism.

It has been claimed that the term constitutional monarchy denotes a monarchy where it does not matter who is monarch. This is supposedly because the monarch is just to see to it that the Constitution is upheld. Now, if we apply an equivalent definition to constitutional democracy, this term would denote a system where it does not matter who the people are — or who the politicians are. They are just there to see that the Constitution is upheld. Does that sound like any democracy you know?

The election of Danish Prince Carl as King of Norway and his taking the name Haakon VII are often referred to as the establishment of a new monarchy. This is not so. Notwithstanding propaganda from the time giving another impression, no new monarchy was established. Of course, the monarchy was different after 1905 than before. However, the Swedish monarchy was different after the total emasculation of the King in the 1970’s, but it still is not referred to as a new monarchy as if it were a newborn baby. The Norwegian throne was the same through the events of 1905. It became vacant by King Oscar II’s abdication on October 26, 1905. Through a referendum — often, erroneously, referred to as a vote on the form of government — the people concurred in asking the Danish Prince Carl to accept this throne.

Constitutional amendments were passed in 1905, including introducing a requirement that an heir to the throne had to be born in wedlock. They were passed unconstitutionally in November because of the new constitutional situation. The union was gone, and provisions no longer relevant were amended. It is often referred to as "emergency law." It was Parliament that had acted unconstitutionally in the first place, so that’s a pretty poor excuse. In a way you could say our Constitution is from 1905, since it at that time was unconstitutionally amended. However, it is dated May 17, 1814. No formal changes were made to our Constitution in November 1905 regarding royal powers.

The lack of formal constitutional changes notwithstanding, what rose out of 1905 was basically a parody of a republican form of government, i.e., a republic in a monarchy’s clothing. The Swedish-Norwegian union was a construction of the age of dynastic monarchies. The "new" monarchy was a "national monarchy," a concept mainly promoted by Sigurd Ibsen, son of Henrik Ibsen. The concept of national monarchy was basically that the monarchy belonged to the nation, and this concept broke radically with the old order, where territories belonged to monarchies.

The lack of formal constitutional changes notwithstanding, what rose out of 1905 was basically a parody of a republican form of government, i.e., a republic in a monarchy’s clothing. The Swedish-Norwegian union was a construction of the age of dynastic monarchies. The "new" monarchy was a "national monarchy," a concept mainly promoted by Sigurd Ibsen, son of Henrik Ibsen. The concept of national monarchy was basically that the monarchy belonged to the nation, and this concept broke radically with the old order, where territories belonged to monarchies.

When Prime Minister Michelsen was seeking a unanimous act of Parliament in June of 1905, he was seeking as few changes as possible. The parliament was only to dissolve the union. If there were any old school monarchists in Parliament at the time, they were seriously had.

The events of May and June 1905 provide an excellent recipe for how a king who does not "behave" can be handled. The success of Parliament’s unconstitutional act is a great manifestation of popular sovereignty. So are our two first referenda, which both took place in 1905 — with a three-month interval. The provisional Cabinet acted solely on parliamentary authority from Parliament from June to November in 1905. Those who negotiated with the future King were republicans in principle, and they were decidedly democrats. They had no interest in letting the constitutional order where there was a check on popular or parliamentary power survive. The same kind of people, and to an extent the same people, were "king makers" and "king raisers" in the period following the ascension of King Haakon VII. The premises for the November referendum were also quite clear. The Bernadotte "partisan monarchy" had been discredited. No interference in "self-rule" was to be tolerated.

In the parliamentary debate on the November referendum the not-so-representative Alfred Eriksen expressed:

Everyone knows that if there now is established a monarchy in this country, it will not be a monarchy by the grace of God, it will not even be by the grace of the people; it will at the most be a monarchy by the grace of Michelsen.

The Speaker of Parliament, Carl Berner, who had given Michelsen the idea of declaring the King deposed and the union dissolved almost at the last moment, also spoke. Obviously he was not acting as Speaker at the time. According to Professor of law Ola Mestad this was the most representative position in Parliament:

[W]e have come so far that if we now get our own Norwegian King, we can be sure that it would be a constitutional monarchy we would commence, and thus we would also have complete security for a complete self-government without a trace of limitation.

The provisional Cabinet’s proclamation — according to Mestad, formally a part of the basis of the referendum — says:

The political liberty of a people depends first of all on its constitutional right to decide its own destiny and on the people’s maturity and ability to use the Constitution, — but less on the question on whether the head of state is called King or President. The English people’s political liberty is as complete as that of any other people, and the new Italian monarchy has promoted the development and popular freedom of Italy as safely and quickly as any republic. In the democratic societies of our time the forms of monarchy or republic mean little and by the way prove nothing regarding the political liberty of the people and the size and strength of self-government.

Mestad notes that it is Great Britain, the mother of parliamentarism — or parliamentary government, and Italy with the new powerless King that are the role models, not Norway’s neighbors Sweden and Denmark. Nor is the monarchy that Norway has had a role model. I would add that neither Russia, Germany, nor the Habsburg Empire are set up as good examples.

Fridtjof Nansen, Norwegian polar explorer and national hero and then future Nobel peace laureate spoke on the day before the referendum commenced:

I can understand that there are people who find the republican form of government more ideal, I am myself not very fond of the monarchy, and I would gladly take part in abolishing it if anyone with certainty could give us a form of government that is more ideal and could give us greater advantages for the future, — and if I were certain that the republican form of government were as ideal in reality as it looks on paper. What I have seen of republics, and that is of the most developed and high standing, has not convinced me thereof. I have gotten the impression that they are very far from being ideal.

Later on in the same speech he tells the audience:

There is, however, as great differences between the different republics as between republic and monarchy. The American President has more power than any monarch in Europe, even if we include the Tsar. […] In the French Republic there is a president who has no power.

According to Mestad several changes were made regarding the royal office. King Oscar II and his predecessors had advisors in matters of state apart from the Council of State. Haakon VII had no such advisors. Previously documents in cases to be brought before the King’s Council — also known as Council of State or simply the Cabinet — were sent to the King in advance. Not so with King Haakon VII, at least with Haakon VII there were only a few exceptions to the rule that information was only given first at the Council meeting. There was also a question of whether the King could go with the minority in the Council. Prime Minister Michelsen had made it clear that the majority ruled even when the Prime Minister was with the minority. The King did not buy this — at least not immediately — and he asked for a private meeting with Michelsen. King Haakon VII is reported to have said at an occasion when he took a handkerchief out of his pocket:

According to Mestad several changes were made regarding the royal office. King Oscar II and his predecessors had advisors in matters of state apart from the Council of State. Haakon VII had no such advisors. Previously documents in cases to be brought before the King’s Council — also known as Council of State or simply the Cabinet — were sent to the King in advance. Not so with King Haakon VII, at least with Haakon VII there were only a few exceptions to the rule that information was only given first at the Council meeting. There was also a question of whether the King could go with the minority in the Council. Prime Minister Michelsen had made it clear that the majority ruled even when the Prime Minister was with the minority. The King did not buy this — at least not immediately — and he asked for a private meeting with Michelsen. King Haakon VII is reported to have said at an occasion when he took a handkerchief out of his pocket:

This, you see, is something in which I am allowed to poke my nose.

Democratically elected politicians obviously do not want kings poking their noses in "their business" of poking their noses in other people’s business. Democratically elected politicians are moreover far better at poking their noses — or authorizing bureaucrats to do so — in other things than handkerchiefs.

Prince Carl was born and raised in the monarchical age. The basically curbed post-1905 monarchy is probably due to a combination of causes, including pre-1905 events, 1905 events, staunch democratist politicians, and an active choice of Haakon VII of not challenging democracy. He was at times harsh when he had differences with politicians, but he basically kept those differences behind the scenes.

Servility is probably a poor description of the new monarch. He might have done well as an "interfering" monarch. I was once told that with the way it went with monarchies with active monarchs it would have little purpose for Haakon VII to be one. Perhaps, but what is definitely more certain is that the democratic-republican age was not a historically necessity. It can be tactically wise to choose a winning side, but it is not necessarily the right thing to do.

Haakon VII saw as his duty to serve his people. What we have had since 1905 has been denoted a "people’s monarchy." Princess Märtha Louise — the sister of our current Crown Prince — was once interviewed about the expression "people’s monarchy" and what it meant. She answered that a "people’s monarchy" is a monarchy where the monarchy serves the people and not the other way around. Well, any monarchy is there to serve the people. The modern misconception is that the people are best served with unlimited democracy — or with the absolute rule of democratically elected politicians — and monarchs letting this absolutism rule.

There is little doubt — if any — that King Haakon VII took his duty seriously. He is known to have said — adhering to an old king moral — that a king is either completely alive or completely dead. To him it was a disgrace not to show due to bad health. One could say he adhered to the motto of Ibsen’s character Brand:

What you are be so fully and wholly, not partly and divided.

Haakon VII did not always rubber-stamp the decisions of the Cabinet immediately. There were occasions where he had decisions postponed when he was in disagreement with his Cabinet. He at least once called a conference at the Royal Palace to turn his Cabinet. According to former secretary for the Council of State Dag Berggrav, the King had a conference with the Secretary of Defense, the Commanding General, and the Commanding Admiral. His Majesty convinced both the general and the admiral, and then the Defense Secretary turned as well. It has also been said that Haakon VII had a certain space within which to act in foreign policy.

Haakon VII did at least at a couple of occasions threaten with abdication. One could say that this does not leave the King totally emasculated. After all, threatening with abdication can often be the most effective means of getting one’s way. This is true, and Oscar II did at least once threaten to abdicate as King of Sweden. However, what is probably more important than the means that are used to have one’s ways is how the roles are.

A striking difference between Norway’s pre-1905 and post-1905 periods is that prior to 1905 the King was after all King, and the Council was the body of his advisors. After 1905 the Cabinet was "King," and the King was "Council." Before 1905 the Council could try to convince the King and the last resort was threatening to resign. After 1905 it was the King who had to convince the Council of State, and if he picked a fight, he was the one who had to threaten — as the last resort — with his resignation. The roles were basically switched.

It has been claimed that Haakon VII’s no to appointing a Nazi Cabinet in April 1940 is the last we ever saw of personal royal power. However, it was clear also here that the roles were like the said post-1905 roles. The King made it clear that the decision belonged to the Cabinet, but that he no longer would be King if the Cabinet gave in to the invaders.

Another — not so well known — threat of abdication came when politicians wanted to curb the King’s formal powers and strip him of the right to award orders. This was around 1913. The institution of orders was preserved, and the King’s formal powers were left intact. However, in 1913 the last doubt of whether there was any right of veto when it comes to constitutional amendments was removed. The arrangement of the King announcing constitutional amendments, as opposed to sanctioning or giving assent, was then put in writing. [Note: This amendment itself was announced by the King, not sanctioned. Any old school monarchist looking for a quarrel could have some fun with that. Additionally, one could theoretically have a possibility of an "announcement strike" when it comes to a constitutional amendment.] Already in 1911 it had been made clear that any decision in the Council of State had to be countersigned to be valid. At the same time military commands, i.e., from the royal office, were made subject to countersignature. In 1931 the Council of State was stripped of some powers regarding making treaties, but at that point the power already belonged to politicians. The power was moved from the Council of State to Parliament.

Professor of history Ole Kristian Grimnes believes that the victory of parliamentarism was secured with the events of 1905. So do Professor of political science Trond Nordby and Professor of law Ola Mestad. Some claim the transition to parliamentarism was not completed until the passing of the Act of Accountability in 1932. King Haakon VII appointed the first Labor Cabinet in 1928, defying advice from the politically established parties on the right. This is a defiance of parliamentarism. However, no clear alternative was presented to His Majesty, and it was clearly a part of a strategy of building a monarchy where also socialists were included — "the people’s monarchy." It was probably not a move to install a Cabinet of the King’s liking. Moreover, this Cabinet lived for no longer than 18 days, after having fallen by a parliamentary vote of no confidence, which it respected. Why the King treated the national socialists, whom he refused audience, differently than those who had sympathy with the Soviet regime we will leave here.

The Act of Accountability clearly states that members of the Cabinet are accountable to the Impeachment Tribunal for upholding the Constitution, other laws, and acts of Parliament and avoiding what is harmful to the realm. Violating the Constitution, breaching other laws, or contributing to something harmful to the realm may result in up to 10 years imprisonment. Being disloyal to acts of Parliament, however, may only result in up to 5 years imprisonment. Of course, in practice the Act of Accountability only applies to violations of the Constitution that Parliament finds troublesome. So a member of the Cabinet may find it better to violate the Constitution than to defy an act of Parliament in spite of the higher level of punishment for violating the Constitution. Moreover, a vote of no confidence — so it seems like someone is holding someone responsible — is more likely in a political milieu where "everyone scratches everyone else’s backs" instead of actually giving real content to the word accountability.

When World War II was over, King Haakon VII’s authority was arguably at a peak. He had led the resistance from London with his Cabinet, which many did not have much confidence in. Haakon VII headed the Council of State every Friday, which still is the normal day for Cabinet meetings, with few exceptions during the exile period at what today is the Norwegian ambassadorial residence in London. He lived at Windsor Castle due to the risk of bombings in the area of the embassy.

According to former employee with the Royal Norwegian Court Carl-Erik Grimstad, there were efforts made to revive personal royal powers at this time. Grimstad calls them political tinkers — a mostly derogatory phrase meaning basically someone who minds matters he does not have sufficient knowledge about, etymologically arising from Ludvig Holberg’s The Political Tinker. I do not know about those behind this proposal when it comes to the term political tinker, but democracy has steadily reduced requirements as to knowing what you are doing or talking about when engaging in politics. Age requirements are no exception. For instance, the voting age in 1905 was 25 years. Today it is 18 years. In 1905 the age requirement for being a member of Cabinet was 30 years. In the 1970’s it was reduced from 30 to 18. Mass democracy’s worship of lack of knowledge and wisdom is nothing to celebrate. Rolling some of it back would be progress. One way of doing this could be restoring some royal power. Grimstad should be more careful with the phrase political tinker. Using the term against limiting democracy suggests not knowing the anti-democrat theme of The Political Tinker.

Haakon is said to have disapproved of the proposal of increased royal powers, as it would supposedly destroy everything he had built up since he came to Norway in 1905.

There was a coronation a hundred years ago today in Trondhjem. One could think that with this coronation that all the outer, ceremonial, and symbolic stuff related to the monarchy remained intact. This is not so. Prime Minister Michelsen hated what he called royal posture. The uniforms of the members of Cabinet and civil officials were abolished the day before Haakon VII landed in Christiania. Royal heralds were abolished. The Royal Order of the Norwegian Lion was never formerly abolished — at least not in the correct manner — but it was never awarded after 1905. The Prime Minister was no longer to be addressed as "Excellency." According to an oral private statement by Professor of law Ola Mestad, “Excellency” was something Michelsen got rid of. There was a considerable republican sentiment in Norway in 1905, and the theme often went that if we were to have a monarchy, it was to be as republican as possible. Michelsen’s own vision for the monarchy was "a King as simple as the people itself."

Some ceremonial stuff remained though. Up until the end of the reign of King Olav V there was the institution of dissolving Parliament — with a ceremony with the King — at the end of each parliamentary year. It was then abolished. This happened long after people had stopped questioning the legitimacy of Parliament being convened all year round. Now, Parliament does have vacations. Norwegians are, however, so brainwashed by egalitarianism that they have a tendency to complain that parliamentarians have longer vacations than other people instead of rejoicing over the long parliamentary vacations and demanding more of it so that Parliament can do less wrong.

Some ceremonial stuff remained though. Up until the end of the reign of King Olav V there was the institution of dissolving Parliament — with a ceremony with the King — at the end of each parliamentary year. It was then abolished. This happened long after people had stopped questioning the legitimacy of Parliament being convened all year round. Now, Parliament does have vacations. Norwegians are, however, so brainwashed by egalitarianism that they have a tendency to complain that parliamentarians have longer vacations than other people instead of rejoicing over the long parliamentary vacations and demanding more of it so that Parliament can do less wrong.

In 1905 oaths were an important part of official life. Until 1899 one had to give an oath to the Constitution in order to be registered as a voter. Many of the members of Parliament in 1905 were still bound by that oath. In addition, there were officers’ and officials’ oaths, and their oaths were to King and Constitution. In November of 1814 there was a parliamentary oath to King and Constitution, but according to the parliamentary archives there has been no such oath since then. There never really was an equivalent to the British parliamentary Oath of Allegiance. Today, there is only the officials’ oath left, and it may be replaced by affirmation — in the case of foreigners, left out — in addition to the King’s and that of the Crown Prince. Moreover, today there are few officials in Parliament or Cabinet, if any, and the few certainly would not take their oaths as seriously as in 1905. Also, according to historian Nils Ivar Agøy, the court system has announced that oaths have reduced significance. Of course, given the way the American President sticks to his oath one could wonder what the point with oaths is.

In 1905 it was a two-way street. Today it is a one-way street. The royal office is basically a subject to democracy. The price we pay for this is not negligible. In the days of Henrik Ibsen it was normal to sign letters to the King with, e.g., "Underdanigst," which would translate into something like "Your subject." This goes for Ibsen himself as well. Tell an average Norwegian today that he is someone’s subject, and he will jump up and shout you down. Yet, we are today more in subjection in practice than Ibsen and his contemporaries probably ever would have accepted being.

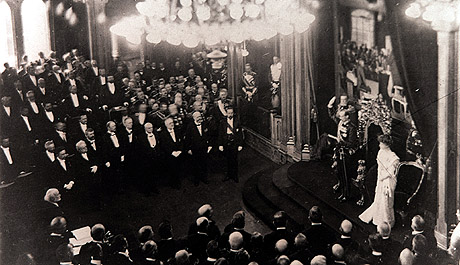

June 22, 1906 was coronation day. Norwegian coronations had been more in line with the concept of popular sovereignty through the 19th century. E.g., when giving their coronational oaths the monarchs as Kings of Norway raised two fingers against the public, as opposed to in Sweden where the fingers were placed on the Bible. It must be noted, however, that according to the original Norwegian Constitution of 1814, the King was to be King by the grace of God and according to the Constitution of the Realm. Moreover, although a bishop led the ceremony, the Prime Minister took part in placing the crown on the King’s head. So when we were having our "more democratic" and simpler coronation of 1906 — when the royal couple was driven in a horse-drawn carriage to the cathedral, instead of walking under a "throne heaven" — Michelsen’s placing the crown on the monarchs head was only new in the sense that it was the first time a parliamentary Prime Minister did this. It is tempting to see this as a symbol of the new monarch as King by the grace of Michelsen. The Prime Minister had no part in the anointment. Given King Oscar II’s hard feelings there was no official Swedish representation at the ceremony.

The die-hard republicans had tried to stop the coronation in 1906. They wanted it all postponed until Parliament could vote on amending the Constitution to abolish the coronation and anointment. They did not succeed. However, in 1908 they succeeded in striking the provision on coronation and anointment from the Constitution against two honorable votes. The institution supposedly belonged in the Middle Ages and "our neighboring countries could be said to have abolished the institution." Well, Norway’s first coronation brought about a law-bound royal office, according to royal biographer Langslet. I guess law-bound authority belongs in the Middle Ages. Now the god Demos was to rule, and god Demos cannot have the competition which a coronation — and especially an anointment — represents. Popular sovereignty was to rule, and so the coronation had to go. As for the claim about "our neighboring countries," Russia and the United Kingdom were our neighbors at the time. Now, Sweden and Denmark are generally the countries included in that term. King Oscar II had passed away only three months before the constitutional amendment. The new Swedish King, Gustaf V, did not want the pomp and circumstance of a coronation. To say that this constitutes abolition is dubious at best. Politicians have strange ways of reaching conclusions.

King Olav V and his son King Harald V both had blessing ceremonies — sometimes erroneously referred to as coronations. This kind of ceremony is not an act of state. The coronation with its anointment was. The remaining act of state for our monarch when ascending the throne is the oath given in Parliament. The fact that King Haakon VII held his hand high above his head, more like kings of old, his son, King Olav V, held his hand up more like we see American presidents at their inaugurations, and our present King Harald V did not hold his hand up at all also illustrates the decline in the monarchy.

King Olav V is known for having taken the city train when going skiing during the petroleum crisis of the 1970’s. The Norwegian royals go in cars and other modern forms of transportation for official ceremonies. If you want royal carriages and horses, you have to go to places like Copenhagen and London. Of course, I am not suggesting that monarchy belongs in the past just like horses and carriages. In a sense it is a good thing that the royals travel in cars to Parliament for the opening ceremony. It shows that monarchy has a place in the modern world. However, one cannot avoid getting the impression that the seeming obsession with using modern transportation is connected with an obsession of distancing the "new" Norwegian monarchy from the past.

It is important to note that all the ceremonial stuff and pomp and circumstance of monarchies are important, but they are not the core of the monarchical system.

In Ibsen’s The Pretenders Haakon tells Count Skule:

What is it that’s tempting you? The King’s ring, the cape with a scarlet edge, the right to sit three steps above the floor; — disgrace, disgrace, — was that being king, then I would throw the kingdom in your hat as I throw a small coin to a beggar.

In Ibsen’s Emperor and Galilean a grain merchant by the name of Medon comes to Emperor Julian complaining about a man wearing a scarlet cape. The Emperor tells Medon to come the next morning for some scarlet boots. The Emperor tells Medon:

These boots you will carry to Alites, put them on him and tell him that he definitely must put them on whenever he hereafter gets the idea to show himself in a scarlet cape in the light of day —

After a short interruption by Medon the Emperor continues:

— and when you so have done, you can tell him from me that he is a fool if he believes to be honored by the scarlet cape without owning the power of scarlet.

Although 1905 in several ways marks the end of the old order in Norway, there are  ways in which it was not an end of the old order. The House of Glücksborg, as a branch of the House of Oldenborg was more of the old order than the House of Bernadotte, which was a product of the French Revolution.

ways in which it was not an end of the old order. The House of Glücksborg, as a branch of the House of Oldenborg was more of the old order than the House of Bernadotte, which was a product of the French Revolution.

Moreover, Crown Prince Olav was to be educated specially. He had private teachers, though he did also go to public school. Nowadays, it is almost seen as a matter of course that princes and princesses are to be sent to kindergulags — popularly known as daycare centers and kindergartens — and to public "schools," whose educational qualities can be seriously questioned. Even though it still can be said that princes and princesses get life-long training, this educational egalitarianism, which no one should be subjected to, can severely jeopardize the concept of the monarch’s special training for the job. The value of monarchy is quite reduced if the monarch is brought up to be like everyone else.

Furthermore, Crown Prince Olav married Swedish Princess Märtha. That was a part of the old order that survived 1905. It has, however, not survived till today. These days, princes and princesses choose consorts of the lowest order — or as they say consorts with "pasts."

In this day and age, many people see the Norwegian royal family as an exercise in worshiping commonness. Other expressions that can be heard are that it is nice to have the royal family for Constitution Day celebrations on May 17, but otherwise we do not need them.

Every once in a while we hear an argument against the monarchy regarding certain members of the royal family having impunity. First of all, republics too have impunity for the head of state. The American President cannot be prosecuted before he fails to be reelected, resigns, or is removed by impeachment. In Norway, the King cannot be prosecuted, and he cannot be brought in as a witness. Certain other members of the royal family answer only to the King, or a specifically appointed judge — by the King — for this purpose. The King and these other members of the royal family are not above the law, as often is claimed, they are merely beyond prosecution.

It is often claimed that the institution of impunity is a remnant of absolutism, feudalism, or both. It all depends on the mood of the day, and the rather arbitrary use of the terms absolutism and feudalism demonstrate that those who use them mostly do not know what they are talking about. Montesquieu warned about the possibility of being able to prosecute the monarch. It could be used to bring down the royal office — or as he put it:

His person should be sacred, because as it is necessary for the good of the state to prevent the legislative body from rendering themselves arbitrary, the moment he is accused or tried there is an end of liberty.

So a legally irreproachable monarch might as well be a remnant of Montesquieu as it might be of absolutism or feudalism. But very often pundits do not know what they are talking about. They would probably neither know that Montesquieu warned against the executive not being able to restrain the encroachments of the legislature. If not, he warned, the "latter would become despotic," as it would take the "authority it pleased" and "would soon destroy all the other powers." What the despotic legislature, which Montesquieu warned against, does on a near to daily basis today is a much larger problem than a few royals not getting a few speeding tickets. The irreproachable acts of parliamentarians are much more to worry about. Moreover, the public eye on the royal family probably has a much more disciplining effect on the royal family than law courts and the police have on the average commoner. If not, we have a serious problem, and it’s not that the royals are not disciplined enough.

In our time the monarch is almost totally emasculated. So one could say the arguments of Montesquieu no longer are relevant. However, heads of state generally, as mentioned earlier, cannot be prosecuted as long as they are heads of state. Furthermore, the impunity of certain members of the royal house may have a moderating effect in a country where government is increasingly far-reaching. More and more legislation is passed. The common citizen might soon not be able to move his two feet without committing a "crime." His fright of the despotic government may be moderated by the fact that its top representative seems not to care about a little speeding or not wearing a seat belt. In the case of King Olav V it was about a matter of principle of individual liberty for his people when it came to not wearing a seat belt. Let us care about the irreproachable acts of Parliament instead. That’s a far greater problem than the largely theoretical debate about royals "not being accountable for their actions."

Our royal office is not totally emasculated. There are certain personal prerogatives remaining, such as the right to approve consorts of princes and princesses, the right to award orders, and the right to appoint members of the royal court. The meetings of the Council of State, which His Majesty still formally appoints, are still generally held at the Royal Palace in Oslo. All Cabinet decisions must be made before either the King or the Crown Prince Regent, save when these have been relieved of the duty of holding Cabinet meetings due to bad health or travel. The Cabinet often comes together without any royals present to discuss and decide things in reality. However, decisions must formally be made either in an official Council of State meeting or by a single Cabinet member if he has been granted the right to do so in the matter.

The constitutional provisions giving the King relief from heading Council of State meetings have for a long time been interpreted liberally, and the argument goes that it does not do any harm, since the royal office does not really take part in the decisions. This is, however, not completely true. The King or the Crown Prince may ask questions. Direct initiative to have cases postponed for instance has not come from the royal office since the days of Haakon VII. If the royal office is not represented, there may be questions that are not asked, and questions have had consequences in the past. They may have so in the future as well.

Not only are questions asked. The royal office may ask for more information. King Olav V did just that, especially in cases concerning pardons. Often information is given in separate meetings, and there are regular meetings with the King and the Prime Minister and with the King and the Secretary of Foreign Affairs. Moreover, King Olav V is said to have been furious when he heard of leaks. The phenomenon of the media getting hold of cases before they were at his table was not viewed friendly. However, there was no question that he would sign whatever he was asked to sign. He even rubber-stamped legislation on abortion, an issue he was deeply concerned with personally.

As for the mentioned orders, there are absolutely good reasons for keeping these outside the political sphere. That is not to say that this institution could not be kept outside the political sphere without being protected by the royal office, but it seems to be going quite well, and so there is no reason to put it at risk.

The question has been asked whether the institution of holding meetings of the Council of State before the royal office is unnecessary formalism. Well, everyone going to a Cabinet meeting at the palace knows that this is serious business. The Cabinet Secretaries have to be well prepared. They know the King may ask questions. Questions may be asked in the following public debate as well, but it probably is a good thing that an experienced authority may ask questions before the matter becomes a question of saving face. Abolishing the institution will probably not make things much worse. After all, the partisan Cabinet basically does what it wants. However, the possibility of things getting better is close to — if not at — zero. Moreover, abolishing the institution will probably also abolish the opportunity of the monarch acting in an emergency. The moderating effect of the weak royal office should not be overrated, but not underrated either. Those who want to abolish the monarch’s overseeing the work of the Cabinet either hate the monarchy, hate anything that would moderate popular or parliamentary rule, or underrate said moderating effect.

Stripping the monarch of more power would probably prevent him from even acting in crises and unclear political situations. In emergencies is perhaps when we need modern monarchs the most. Stripping them of their powers when we do not see such an emergency coming is easy. The problem is that we will find out too late what an error we have made.

Personally, I would restore the royal powers at least to the level at which they were on February 26, 1884 — the day before the "verdict" of the Impeachment Tribunal against the Selmer Cabinet, a "verdict" that was substantial in bringing about parliamentary government in Norway — tomorrow if I could. The problem, of course, is the lack of realism in this plan. Effective royal powers are probably not going to be seen in Europe anytime soon, save the principalities of Liechtenstein and Monaco.

So why can’t we just abolish it altogether? We can have "real checks and balances" with a constitutional republic, which — it is said — is a concept that is more likely to succeed. It is perhaps true that we can have more real checks and balances than in the current system — but not compared to the real mixed governments of old — by abandoning the monarchy. However, that implies going for something basically like the American presidential system.

A relevant question then is how effective has the American system been lately at keeping the reach and the size of the state in check. The likelihood of such a system replacing the current system is furthermore minimal. Moreover, the Norwegian establishment hates the American system. Some of the reasons for this are good, some not. The Norwegian establishment will never go for a system like the American one. Besides, the American system is a one-party system with two party wings; the Demopublicans and the Republicrats. This party system controls both the legislative and executive branches of government, and it is quite successful at limiting the judiciary’s ability to serve as a check and balance on the other two branches. At times the party system even wants to fill the judiciary with loyal partisans. To call this system "real checks and balances" would be an insult to the late French Baron of Montesquieu — and other thinkers of limited government for that matter.

A republican form of government would require an amendment to the Constitution. This is generally done by Parliament. Is Parliament likely to set up a system that in any real way will limit the power of Parliament? And in the unlikely event of Parliament ceding the authority of amending the Constitution to some other body, this body will hardly consist of representatives who will give us a more liberty-friendly constitution than what we in reality have today.

One of the most likely options when abolishing the monarchy would be replacing the monarch with a Parliament-appointed president. Such a president would take care of ceremonial duties and chair the Cabinet meetings. He would have no more power than the King has today. He would have his authority from Parliament. An active or retired politician asking questions to the Cabinet instead of a King would hardly be an improvement.

Probably it would be a change for the worse. We would basically exchange the non-partisan review of Cabinet decisions with a partisan review and a politicization of the office of head of state.

Probably it would be a change for the worse. We would basically exchange the non-partisan review of Cabinet decisions with a partisan review and a politicization of the office of head of state.

Besides, the Swedish constitutional system is today designed in such a way that it is Parliament, not the King, that in practice as well as formally appoints the Prime Minister. The role of appointing the Cabinet has already been taken away from the King of Sweden. If one wanted "real checks and balances," one could simply let the office of Prime Minister be put up for popular election. Yet, there are republicans who claim that the only way to have "separation of powers" is to abolish the monarchy.

If I were to give one good reason for abolishing the monarchy, it would be the level to which the monarchy has fallen in several respects. It no longer exercises power. If it did, it would probably not survive. Members of the royal house strive for being like commoners. However, I do not believe replacing the monarchy would make things better. Moreover, we could easily be fooled — overrating the non-democratic element of the government — by the present system. This phenomenon of overrating seems to be quite present in the United Kingdom. One could argue that removing the monarchy would be an eye-opener in this respect.

Norway is said to have the most egalitarian culture in the Western world. Yet, we have a monarchy. Notwithstanding the royals’ efforts to be basically like everyone else, this monarchy represents a substantial element of inequality. Some may argue that it is forced inequality, funded by the tax-payers, and so it must go. Those who want to abolish the monarchy because they are against all kinds of inequalities are not to be trusted. Those who generally believe that inequality is good, but that monarchy represents the wrong kind, should think about the consequences in society of removing the monarchy for egalitarian and anti-egalitarian sentiments. Notwithstanding how far the emasculation of the royal office has come, the monarchical element of our governmental system keeps the principle of inequality alive. It also keeps the principle of non-democratic government — or a democratic government with non-democratic elements — alive. Removing the monarchy will be at our peril.

Additionally, there are worse things that can happen to a country than being a Western democracy. One could easily doubt — with the level to which monarchs have been emasculated — that monarchs will ever intervene, even when the worst crisis or emergency occurs, but there is at least a hope. Yves R. Simon notes:

Although the king of Great Britain and the Scandinavian kings may do little governing, they certainly play a very important part in the political life of their kingdoms. No matter how democratically inclined they may feel, these hereditary presidents of democracies, by the very fact that they are designated not by election but by birth, are nondemocratic characters. Yet few supporters of democracy would wish monarchy to be suppressed in these countries. The almost unanimous opinion is that, under the circumstances, monarchy is useful in several respects — that it is useful, in particular, for the protection of democracy. It is easy to see that by accident (but such accidents are frequent) a nondemocratic principle may serve democracy by holding in check forces fatal to it. One recognized drawback of democratic institutions is that they may occasion sharp strife among parties or factions. When people are sufficiently exhausted by such strife, the situation is ripe for the one-party system and dictatorship. Accordingly, one major need of democracy is protection against the destructive effects of domestic conflicts. That such protection, under definite circumstances, should be best procured by such a nondemocratic factor as a hereditary monarch is perfectly intelligible.

A lot of people see the monarchy as a symbol of subjection, in spite of the history of the republican form of government through the 20th century. The Soviet Union, Mao’s China, and Weimar Germany are examples that tyranny is at least as good a characteristic of republics as that of monarchies — if not more. Liberty has declined in Europe almost in line with the emasculation of its monarchs and the rising esteem of democratic republics. That does not exactly make the republican form of government an icon of liberty.

However, the most convincing argument against this concern with symbols I would draw from the pen of Henrik Ibsen. He wrote to his fellow writer Bjørnson on the issue of "the pure Norwegian flag." Ibsen deplored the concept of caring for symbols, ideas, and theories to the extent that progress in practice is not made.

Leave the emasculated monarchs of Europe as they are, save if you are interested in increasing their powers. They do not do much harm. You cannot get a king of your choosing, but you will probably not get a president of your choosing either, unless you consider getting the candidate you voted for among very few as president as your choice.

Care about real progress and not about "intolerable symbols of subjection." Let us keep the "constitutional monarchs" for ceremonies and emergencies.

Care about real progress and not about "intolerable symbols of subjection." Let us keep the "constitutional monarchs" for ceremonies and emergencies.