The Southern political tradition, in practice and theory, is one of its most valuable contributions to America and the world. The one constant theme of that tradition from 1776–through Jefferson, Madison, John Taylor, St George Tucker, Abel Upshur, John C. Calhoun, the Nashville Agrarians, Richard Weaver, M. E. Bradford, down to the scholars of the Abbeville Institute–is a systematic critique of centralization. Nothing comparable to it exists elsewhere in America or in Europe.

A criticism of centralization presupposes that decentralization is a good thing. But why is that? The answer is complex and requires viewing what was happened in 1776 from a trans Atlantic perspective. The Declaration of Independence is merely the American version of a conflict that had been going on in Europe since at least the 17th century between the emerging centralized modern state and a revived interest in the classical republican tradition which goes back to the ancient Greeks.

The South Was Right!

Best Price: $21.38

Buy New $36.15

(as of 10:45 UTC - Details)

The South Was Right!

Best Price: $21.38

Buy New $36.15

(as of 10:45 UTC - Details)

There are four principles to this republican tradition: First, republican government is one in which the people make the laws they live under. But, second, they cannot make just any law. The laws they make must be in accord with a more fundamental law which they do not make but is known by tradition. Third, the task of the republic is to preserve and perfect the character of that inherited tradition. And finally, the republic must be small. It must be small because self-government and rule of law is not possible unless citizens know the character of their rulers directly or through those they trust.

The Greeks created a brilliant civilization that was entirely decentralized. It was composed of 1,500 tiny independent republics strung out from Naples to the Black Sea. Most were under 10,000. One of the largest was Athens with around 200 thousand people. For over two thousand years, up to the French Revolution, republics seldom went beyond 200-300 thousand people, and the great majority were considerably smaller.

In contrast, a modern state is supposed to be large. Thomas Hobbess, published in 1651 the first systematic theory of the modern state. He titled the book “Leviathan,’ a large sea monster. It contains a central government endowed with irresistible and indivisible power over individuals in a territory. Unlike republicanism, it does not require, self-government or tradition. Nor does it require the rule of law since the central authority itself can make law. Its purpose is to contain anarchy by enabling autonomous individuals to pursue their own ends in a condition of enlightened self-interest called “civil association.” Such a regime is compatible with an association of strangers, as in a regime of traffic regulations.

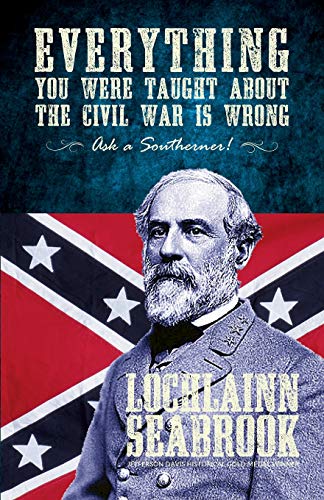

Everything You Were Ta...

Best Price: $16.20

Buy New $14.98

(as of 09:10 UTC - Details)

Since the only goal of the modern state is “civil association,” there is no internal limit to its size. In fact, the larger the better because outside the realm of civil association lies anarchy or its ever present threat. The logical extension of this is global government or as close an approximation as possible. Although a modern state may expand in size indefinitely, its territory cannot be divided by secession because if one set of individuals could lawfully secede, so could any other set, and so on within each set, to the unraveling of all government.

Everything You Were Ta...

Best Price: $16.20

Buy New $14.98

(as of 09:10 UTC - Details)

Since the only goal of the modern state is “civil association,” there is no internal limit to its size. In fact, the larger the better because outside the realm of civil association lies anarchy or its ever present threat. The logical extension of this is global government or as close an approximation as possible. Although a modern state may expand in size indefinitely, its territory cannot be divided by secession because if one set of individuals could lawfully secede, so could any other set, and so on within each set, to the unraveling of all government.

Here we have two incompatible models of government. The small classical republic and the indefinitely large modern state. But there is a third model to consider. Medieval civilization was also decentralized, and it was vast in scale. It was a mosaic of thousands of independent and quasi-independent political units: kingdoms, principalities, dukedoms, bishoprics, papal states, republics, free cities, and tens of thousands of titled manors.

The medieval contribution to politics is the idea of a federated polity where various independent political units are held together in a larger realm by compacts and traditional hierarchies. As we will see shortly, it is through the logic of the medieval federation that the Southern tradition sought to bring together the best aspects of the small republic with those of the large modern state.