More than any other presidency in modern history, Donald Trump’s has been a veritable sociopolitical wrecking ball, deliberately stoking conflict by playing to xenophobic and racist currents in American society and debasing its political discourse. That fact has been widely discussed. But Trump’s attacks on the system of the global U.S. military presence and commitments have gotten far less notice.

He has complained bitterly, both in public and in private meetings with aides, about the suite of permanent wars that the Pentagon has been fighting for many years across the Greater Middle East and Africa, as well as about deployments and commitments to South Korea and NATO. This has resulted in an unprecedented struggle between a sitting president and the national security state over a global U.S. military empire that has been sacrosanct in American politics since early in the Cold War.

And now Bob Woodward’s “Fear: Trump in the White House” has provided dramatic new details about that struggle.

Trump’s Advisers Take Him Into ‘the Tank’

Trump had entered the White House with a clear commitment to ending U.S. military interventions, based on a worldview in which fighting wars in the pursuit of military dominance has no place. In the last speech of his “victory tour” in December 2016, Trump vowed, “We will stop racing to topple foreign regimes that we knew nothing about, that we shouldn’t be involved with.” Instead of investing in wars, he said, he would invest in rebuilding America’s crumbling infrastructure.

Killing the Deep State...

Best Price: $3.14

Buy New $7.17

(as of 05:50 UTC - Details)

Killing the Deep State...

Best Price: $3.14

Buy New $7.17

(as of 05:50 UTC - Details)

In a meeting with his national security team in the summer of 2017, in which Secretary of Defense James Mattis recommended new military measures against Islamic State affiliates in North Africa, Trump expressed his frustration with the unending wars. “You guys want me to send troops everywhere,” Trump said, according to a Washington Post report. “What’s the justification?”

Mattis replied, “Sir, we’re doing it to prevent a bomb from going off in Times Square,” to which Trump angrily retorted that the same argument could be made about virtually any country on the planet.

Trump had even given ambassadors the power to call a temporary halt to drone strikes, according to the Post story, causing further consternation at the Pentagon.

Trump’s national security team became so alarmed about his questioning of U.S. military engagements and forward deployment of troops that they felt something had to be done to turn him around. Mattis proposed to take Trump away from the White House into “the Tank” at the Pentagon, where the Joint Chiefs of Staff held their meetings, hoping to drive home their arguments more effectively.

It was there, on July 20, 2017, that Mattis, then-Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and other senior officials sought to impress on Trump the vital importance of maintaining existing U.S. worldwide military commitments and deployments. Mattis used the standard Bush and Obama administration rhetoric of globalism, according to the meeting notes provided to Woodward. He asserted that the “rules-based, international democratic order”—the term used to describe the global structure of U.S. military and military power—had brought security and prosperity. Tillerson, ignoring decades of U.S. destabilizing wars in Southeast Asia and the Middle East, chimed in, saying, “This is what has kept the peace for 70 years.”

Trump said nothing, according to Woodward’s account, but simply shook his head in disagreement. He eventually steered the discussion to an issue that was particularly irritating to him: U.S. military and economic relations with South Korea. “We spend $3.5 billion a year to have troops in South Korea,” Trump complained. “I don’t know why they’re there. … Let’s bring them all home!”

At that, Trump’s chief of staff at the time, Reince Priebus, recognizing that the national security team’s effort to get control of Trump’s opposition to their wars and troop deployments had been an utter failure, called a halt to the meeting.

In September 2017, even as Trump threatened in tweets to destroy North Korea, he was privately hammering aides over the U.S. troop presence in South Korea and repeatedly expressing a determination to remove them, Woodward’s account reveals.

Those Trump complaints prompted H.R. McMaster, then the national security adviser, to call for a National Security Council meeting on the issue on Jan. 19. Trump again demanded, “What do we get by maintaining a massive military presence in the Korean peninsula?” And he linked that question to the broader issue of the United States paying for the defense of other states in Asia, the Middle East and NATO.

Mattis portrayed the troop presence in South Korea as a great security bargain. “Forward-positioned troops provide the least costly means of achieving our security objectives,” he said, “and withdrawal would lead our allies to lose all confidence in us.” The chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Gen. Joseph Dunford, argued that South Korea was reimbursing the United States $800 million a year out of the total cost of $2 billion, thus subsidizing the United States for something it would do in its own interests anyway.

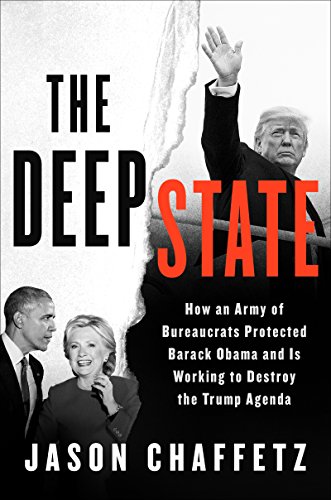

The Deep State: How an...

Best Price: $5.03

Buy New $17.05

(as of 02:10 UTC - Details)

The Deep State: How an...

Best Price: $5.03

Buy New $17.05

(as of 02:10 UTC - Details)

But such arguments made no impression on Trump, who saw no value in having troops abroad at a time when the United States itself was crumbling. “We have [spent] $7 trillion in the Middle East,” Trump said at the end of the meeting. “We can’t even muster $1 trillion for domestic infrastructure.”

Trump’s belief that U.S. troops should be pulled out of South Korea was reinforced by the unexpected political-diplomatic developments in North and South Korea in early 2018. Trump responded positively to North Korean leader Kim Jong Un’s offer of a summit meeting and signaled his readiness to negotiate with Kim on an agreement that would both denuclearize North Korea and bring peace to the Korean peninsula.

Before the Singapore summit with Kim, Trump ordered the Pentagon to develop options for drawing down those U.S. troops. That idea was viewed by the news media and most of the national security elite as completely unacceptable, but it has long been well known among military and intelligence specialists on Korea that U.S. troops are not needed—either to deter North Korea or to defend against an attack across the DMZ.

Trump’s willingness to practice personal diplomacy with Kim and to envision the end or serious attenuation of the U.S. troop deployment in South Korea was undoubtedly driven in part by his ego, but it could not have happened without his rejection of the ideology of national security that had dominated Washington elites for generations.