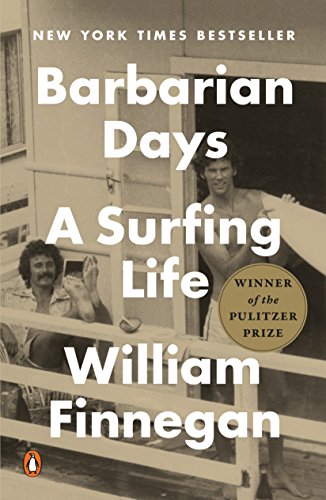

How high of a standard of living did young baby boomers enjoy, especially those of us fortunate to grow up on the then lightly populated West Coast? That question kept coming to mind while reading the acclaimed 2015 memoir of a youth spent at the beach in California and Hawaii, Barbarian Days: A Surfing Life, by William Finnegan, now a veteran war correspondent for The New Yorker.

Comedian Garry Shandling’s most reliable joke was about taking a drive in the country and doing what everybody does when he first sees a cow: rolling down the window and shouting, “Moo.” But, Shandling asked, “What’s the cow thinking?”

“Oh, look, there’s a cow driving a car…. How can he afford that?”

Similarly, while reading Finnegan’s account of his quintessential boomer life of freedom, security, and opportunity enjoying himself in some of the most desirable real estate in the world, I kept asking from my 2018 perspective: How could he afford that?

Surfing may be even more addictive than its counterparts, such as skiing, mountain climbing, and golf. While the waves are free (which, I learned from Barbarian Days, causes surfers no end of grief), the real estate values of adjoining coastal property have only gone up and up over Finnegan’s lifetime. The roll call of places where Finnegan surfed as a boy and young man—Malibu, Newport Beach, Topanga Canyon, Santa Barbara, Honolulu, Santa Cruz, Maui, Australia’s Gold Coast, Cape Town, and San Francisco—reads like a real estate speculator’s fever dream.

Barbarian Days: A Surf...

Best Price: $2.39

Buy New $9.00

(as of 11:15 UTC - Details)

Barbarian Days: A Surf...

Best Price: $2.39

Buy New $9.00

(as of 11:15 UTC - Details)

From a supply-and-demand perspective, the answer to Shandling’s cow question is obvious: Finnegan could afford to spend thousands of hours surfing in various slices of paradise because he was born in 1952.

Granted, the best year of all to be born was 1946. Following the long baby bust of 1930–45, the country was desperately short of young men. So those born in 1946 went through life with little competition ahead of them. (See the fabulous careers of Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Donald Trump, all born in 1946.)

But 1952 wasn’t a bad birth year for boomer entitlement either: Supply and demand were still in your favor. Moreover, Finnegan’s working-class Irish-American parents had the good sense to white-flight from New York City to spacious Woodland Hills, California.

Before overpopulation, women’s lib, and immigration, America, especially California, had needed its young men, and would therefore put up with a lot from them. Finnegan recounts his occasional worries that his obsession with surfing might be interfering with finishing his degree at a free University of California campus and starting a white-collar career, but decent-paying blue-collar jobs were no problem for a strong young man to find back then.

Indeed, having grown up a dozen miles down the Ventura Freeway and a half-dozen years after Finnegan, his privileged life story is hardly unfamiliar to me. In fact, I kept wondering whether his was the same Finnegan clan I’d been in the Boy Scouts with in Sherman Oaks in 1970.

They weren’t, I eventually determined, but the numerous biographical similarities between these two sets of upwardly mobile Finnegans point out that many boomer Americans were able to afford similar lives before California became quite so crowded. A few years before Finnegan took up surfing at age 10 in 1962–63, the Census measured California’s population at 16 million (versus 40 million today).

Finnegan didn’t grow up rich—he can recall his housewife mom and him bringing lunch to the Reseda gas station where his father was a pump jockey. But there was enormous opportunity in postwar Southern California. His father caught on as a union set worker on TV shows in the 1950s, and by the 1970s was producing Hawaii-Five-O episodes as a specialist in television series set in the fiftieth state. (Hawaii is relatively forgotten today—recall how nobody cared that Barack Obama was the first Hawaiian-born president—but Americans couldn’t get enough of the fiftieth state a half century ago.)

Being from a working-class Irish-American background hadn’t kept Finnegan’s dad from having four children, starting with the author at age 24. Long before his father made it big, he was already earning enough money working with his hands so that the author’s talented mother could stay home with Little Bill and his three siblings. Later, as an empty nester, his mother became a TV executive and garnered 39 IMDb production credits. Life seemed full of possibilities back then.