You probably started crawling when you were about nine months old, and walking at a year. You likely got running around a year later, and learned how to jump not long after that. In the months and years that followed, you got the hang of many other physical movements that helped you explore your world, play with friends, and make it through PE class.

Now that you’re a grown man, you probably don’t think all that much about the different ways you can move your body (unless it’s to note how much more painful some of them feel these days). After all, you’ve been doing such thoroughly simple things like running and jumping for decades now, and they feel completely instinctual. You don’t have to think much about basic physical movements anymore.

That’s the common line of thinking, at least. But it’s a wrong-headed and detrimental perspective.

Current Prices on popular forms of Silver Bullion

That which we believe is “basic” turns out to have layers of complexity we simply haven’t discovered yet.

And while we don’t typically think about them as such, physical movements are skills, and like all skills, they need to be deliberately, regularly, and continually practiced and challenged in order to stay in fighting shape and truly be mastered.

What It Means to Truly Be Physically Skilled

While it’s true that many physical movements are instinctual, and that most men can do them effectively, simply being able to get a job done is not the same thing as doing that job well; having an aptitude for something is not the same thing as being skilled in it.

I can whittle the end of a stick into a sharp point, but that aptitude for carving does not make me a master woodworker.

Likewise, it’s possible to be both physically fit and physically effective, without being physically proficient and efficient. That is, you can possess the ability to perform certain movements well enough to get by, without having refined your technique; you can be well-conditioned and have strength and endurance in spades, without being adept at moving in ways that enhance fluidity, conserve energy, and minimize injury.

It’s also possible to achieve functional fitness without achieving adaptable fitness.

Programs like CrossFit have valuably brought the former category to the fore, and encouraged folks to exercise their bodies in ways that aren’t limited to using Nautilus machines and dumbbells. But even these “functional” workouts are relatively limited and circumscribed in scope. They don’t entirely translate to the environmental and situational demands one faces outside the metaphorical and literal box.

You can do a bunch of plyo box jumps in the gym, but how many landings could you stick in nature, where rocks and ledges don’t have a uniform shape, height, or surface? You can do a dozen pull-ups on a bar, but would you be able to pull yourself up even once on a tree branch? You can carry a sandbag back and forth across a parking lot, but would you be able to carry another person uphill, and over obstacles and debris? You can lift a barbell, but can you lift and shoulder a thick, rough, uneven log? You can run a mile on a treadmill in an air-conditioned environment, but can you run in the wind and the rain — in sweltering heat and frigid cold?

The goal for a man’s physicality should eschew narrowness in favor of an expansiveness that incorporates all of these qualities: effectiveness and efficiency; fitness and proficiency; functionality and adaptability.

A man should be able not only to perform a wide range of movements, but to do so with the best possible technique; he should be able to perform not only a high quantity of movements, but a high quality of them as well. He should not only be able to move, but to move with finesse. And he should be able to perform such movements not only within a gym, but in a variety of terrains, environments, and weather conditions, across a wide range of surfaces, heights, and distances.

Gaining mastery in all of these areas is to become physically well-rounded, or as the MovNat (“natural movement”) system, from which the above philosophy derives, puts it: the goal should be to gain “physical competence for practical performance.”

To truly become physically skilled.

The Practice of Physicality

Physical movements are skills and like all skills, they require practice to master; you may have been born with a natural aptitude for certain movements, but that potential then needs to be intentionally honed and sharpened. A man’s body is both tool and master; with the right level of discipline, knowledge, and dedicated practice, it can be put to an extraordinary, and even inspiring, number of uses.

Practicing physical skills is like practicing any other skills in that you must first master the very fundamentals, and from there strive to steadily increase the level of difficulty you can handle. This requires working in the following areas:

- Technique: Technique involves mindfully using the best body position, form, tension, breathing, etc. to execute a movement efficiently – in a way that expends less energy, increases speed/endurance/strength capacity, and prevents injury.

- Variations: Physical skills have many variations that call for varied techniques; for example, you can jump either vertically or horizontally; you can crawl with your belly on the ground or up on your hands and knees. The more variations you master, the more skilled you become in that movement.

- Volume & Intensity: It’s one thing to be able to perform a physical skill for one rep, or at a short distance. But true physical competence means possessing the ability to go short or long, easy or hard, light or heavy.

- Environmental/Situational Demands: Increasing the complexity of the environment in which you practice physical skills — training on various surfaces, heights, and even in various mental states — makes performing a physical movement more challenging and the skill you earn in that area more adaptable.

Now that you know physical skills must be practiced, and how they are practiced, the next question, of course, is what set of skills you ought to be practicing.

The 10 Physical Skills Every Man Should Master

While there are many ways that the human body can move, there are arguably 10 skills that form the very essentials of physical competence: balancing, running, crawling, jumping, climbing, traversing, lifting, carrying, throwing, and catching. These skills form the backbone of the MovNat system, and are also very similar to the essential “military physical skills” delineated in the Marines Physical Readiness Training for Combat manual – movements the “Fast and skillful execution” of which, “may mean the difference between success and failure on the battlefield.” These are the skills that will allow you to ably carry out day-to-day tasks, save yourself and others in emergencies, and navigate your environment with confidence, and even exhilaration.

Below we provide a brief introduction to the 10 physical skills every man should master, with descriptions and illustrations based on the (incredibly informative) Level I MovNat Certification manual. The article is designed to provide a broad overview of each skill, covering its practical applications, some of its possible variations, and ways to challenge yourself and level up in that area.

The illustrations demonstrate the very basics of these movements, as well as some of their variations. There isn’t room in this article to show every variation of every skill, nor to offer step-by-step instructions on technique; text is not the best way to learn physical technique besides. In many cases, I’ve linked to very brief demonstrations of these skills by MovNat’s founder, Erwan LeCorre. But to really develop your technique, I recommend getting in-person coaching by attending a MovNat workshop or certification (you can read my review of it here), or signing up for their online coaching (which is coming soon).

(I have no financial affiliation with MovNat — I just dig their philosophy and approach to physicality; they’re the masters of mastering physical skill.)

Balancing

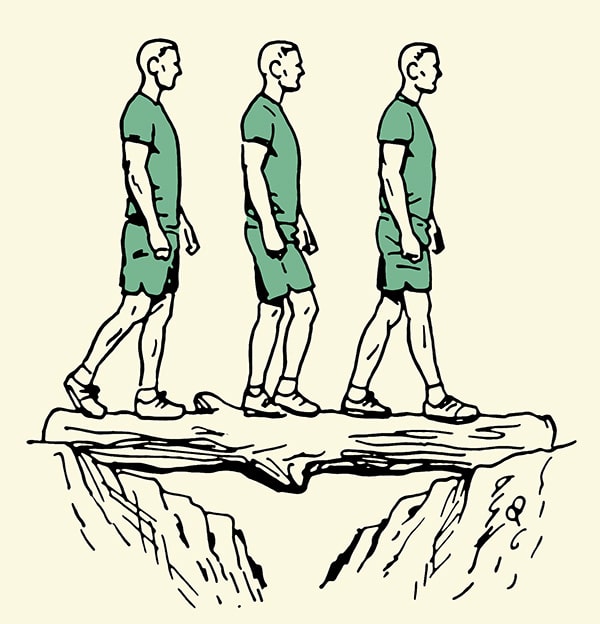

Even when you’re just standing up, you’re countering and managing the forces of gravity, and thus balancing. Ditto for every movement you make. Balance as a skill, however, involves a more challenging context, when a surface you’re navigating is more unstable, slippery, and most typically, narrower than those you typically encounter, e.g., crossing a log or railing.

Because balancing is often engaged in a slower way, and is thus neither as taxing nor strengthening to one’s anaerobic or aerobic systems as other exercises, it’s often overlooked as an important physical skill. But it’s not only a central component of all movement, it also improves joint stability and enhances mindfulness; the focus required to maintain balance re-connects the mental and physical. Plus, it’s a skill that surely comes in handy when the only way to cross a river, chasm, or other obstacle is by way of a narrow beam.

Balancing is an easy skill to practice in short snatches throughout the day; I’ve in fact got a 2X4 in my living room just for this purpose.

Ways to Practice, Challenge, and Level Up This Physical Skill

- Practice basic balancing with good technique

- Move backwards and sideways on the board/beam

- Pivot on the beam to change direction

- Practice standing on one foot on the beam

- Do a split squat on the beam and stand up without losing your balance

- Do a split squat on the beam and change directions

- Keep your balance while holding a static position (standing on two feet, one foot, crouching, etc.)

- Move quickly across the beam (without sacrificing technique)

- Cross a beam while carrying a weight like a sandbag

- Cross beams of varied heights

- Cross beams that are more narrow, slippery, unstable

- Catch or throw something while crossing the beam

- Perform any of the above right after a bout of strenuous activity/exercise, when your heart rate is elevated

Running

Running, along with walking, constitutes the most basic form of human locomotion. It also constitutes what is arguably the best form of full-body aerobic and anaerobic exercise. The conditioning that comes from running forms a necessary base for performance in numerous recreational activities, as well as team, individual, and combat sports. And whether you’re running to an emergency to lend aid, or away from it to summon help, running is key to surviving and thriving in crisis scenarios.

Running unfortunately also comes with a high rate of injury. While MovNat encourages running with a forefoot/midfoot strike, and even a progression to barefoot running as a way to lower this risk, I’m personally not bullish on people’s ability to significantly change their running form, nor convinced that the forefoot strike is necessarily best for everyone. Heel striking is overly demonized these days, and doesn’t even use more energy as is commonly supposed.

Certainly, improve what you can about your form (including cadence, stride length, and posture), but I believe the best and most effective way to prevent injuries is simply to run less, and “cross-train” more (MovNat encourages this approach as well). All the other exercises listed here, from jumping to balancing to lifting, will improve your all-around strength and agility, and help injury-proof your running. Running on varied surfaces, instead of exclusively on pavement and/or treadmills, will help greatly too.

Run as efficiently as you can.

Ways to Practice, Challenge, and Level Up This Physical Skill

- Practice running with good technique

- Vary speed, distance, and duration

- Run on varied surfaces – in the woods, on sand, etc.

- Practice dodging obstacles and quickly changing directions when you run

Crawling

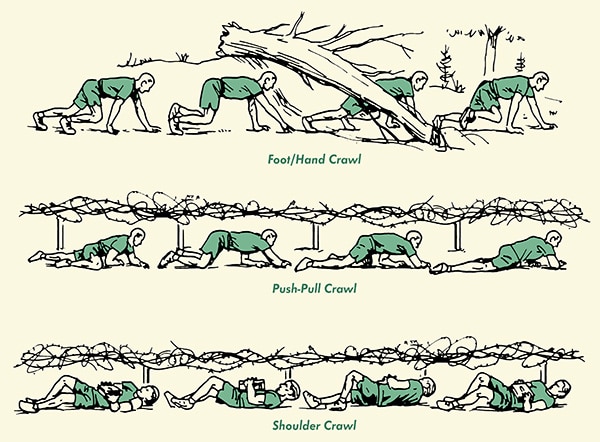

Crawling is likely the first fundamental movement you developed as a baby. Yet as adults, it’s probably the most neglected, perhaps because it seems too “basic” to require practice as a grown-up. But it certainly isn’t.

For babies, crawling is an excellent on-boarding stage for the motor skill development to come, as it engages the whole body, and necessitates coordination between arms and legs. This function still serves adults well. Crawling requires contralateral movement (e.g., moving your right arm and left leg forward at the same time) – which is harder to do at first than you’d think! It encourages mindfulness about your body position, strengthens all your limbs and especially your core, enhances your limberness and agility, and, when performed over a significant distance, provides a great conditioning exercise too. Because of its whole-body benefits, Aaron Baulch, a MovNat instructor here in Tulsa, aptly calls crawling “body armor.”

Crawling is also eminently functional. It allows you to wriggle under low obstacles, keep moving while dangers (e.g. bullets) are present overhead, creep quietly, stalk animals and humans, and ascend/descend steep and slippery surfaces while maintaining balance.

Crawling can be performed with different combinations of hands, knees, feet, and even your backside in contact with the ground, depending on how low you want to get, how quickly you need to move, and whether you need to do things like carry equipment as you crawl.

The Foot-Hand Crawl is a quick crawl good for climbing up a slippery incline and making fast transitions to standing or other movements on the ground. The Push-Pull Crawl is slower, but helps you get lower and closer to the ground. The Shoulder Crawl is slower than the Push-Pull, but uses less energy and allows you to see more of what’s going on around you, as well as carry something as you crawl.