Chapter 2 of The Underground History of American Public Education

Today’s corporate sponsors want to see their money used in ways to line up with business objectives…. This is a young generation of corporate sponsors and they have discovered the advantages of building long-term relationships with educational institutions. ~ Suzanne Cornforth of Paschall & Associates, public relations consultants. As quoted in The New York Times, July 15, 1998

A Change In The Governing Mind

Sometimes the best hiding place is right in the open. It took seven years of reading and reflection for me to finally figure out that mass schooling of the young by force was a creation of the four great coal powers of the nineteenth century. It was under my nose, of course, but for years I avoided seeing what was there because no one else seemed to notice. Forced schooling arose from the new logic of the Industrial Age — the logic imposed on flesh and blood by fossil fuel and high-speed machinery.

This simple reality is hidden from view by early philosophical and theological anticipations of mass schooling in various writings about social order and human nature. But you shouldn’t be fooled any more than Charles Francis Adams was fooled when he observed in 1880 that what was being cooked up for kids unlucky enough to be snared by the newly proposed institutional school net combined characteristics of the cotton mill and the railroad with those of a state prison.

After the Civil War, utopian speculative analysis regarding isolation of children in custodial compounds where they could be subjected to deliberate molding routines, began to be discussed seriously by the Northeastern policy elites of business, government, and university life. These discussions were inspired by a growing realization that the productive potential of machinery driven by coal was limitless. Railroad development made possible by coal and startling new inventions like the telegraph, seemed suddenly to make village life and local dreams irrelevant. A new governing mind was emerging in harmony with the new reality.

The principal motivation for this revolution in family and community life might seem to be greed, but this surface appearance conceals philosophical visions approaching religious exaltation in intensity — that effective early indoctrination of all children would lead to an orderly scientific society, one controlled by the best people, now freed from the obsolete straitjacket of democratic traditions and historic American libertarian attitudes.

Forced schooling was the medicine to bring the whole continental population into conformity with these plans so that it might be regarded as a "human resource" and managed as a "workforce." No more Ben Franklins or Tom Edisons could be allowed; they set a bad example. One way to manage this was to see to it that individuals were prevented from taking up their working lives until an advanced age when the ardor of youth and its insufferable self-confidence had cooled.

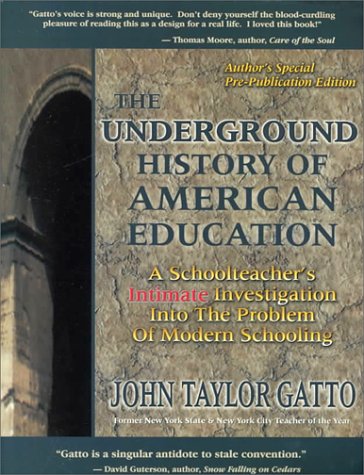

The Underground Histor...

Best Price: $39.03

Buy New $180.99

(as of 07:40 UTC - Details)

The Underground Histor...

Best Price: $39.03

Buy New $180.99

(as of 07:40 UTC - Details)

Extending Childhood

From the beginning, there was purpose behind forced schooling, purpose which had nothing to do with what parents, kids, or communities wanted. Instead, this grand purpose was forged out of what a highly centralized corporate economy and system of finance bent on internationalizing itself was thought to need; that, and what a strong, centralized political state needed, too. School was looked upon from the first decade of the twentieth century as a branch of industry and a tool of governance. For a considerable time, probably provoked by a climate of official anger and contempt directed against immigrants in the greatest displacement of people in history, social managers of schooling were remarkably candid about what they were doing. In a speech he gave before businessmen prior to the First World War, Woodrow Wilson made this unabashed disclosure:

We want one class to have a liberal education. We want another class, a very much larger class of necessity, to forgo the privilege of a liberal education and fit themselves to perform specific difficult manual tasks.

By 1917, the major administrative jobs in American schooling were under the control of a group referred to in the press of that day as "the Education Trust." The first meeting of this trust included representatives of Rockefeller, Carnegie, Harvard, Stanford, the University of Chicago, and the National Education Association. The chief end, wrote Benjamin Kidd, the British evolutionist, in 1918, was to "impose on the young the ideal of subordination."

At first, the primary target was the tradition of independent livelihoods in America. Unless Yankee entrepreneurialism could be extinguished, at least among the common population, the immense capital investments that mass production industry required for equipment weren’t conceivably justifiable. Students were to learn to think of themselves as employees competing for the favor of management. Not as Franklin or Edison had once regarded themselves, as self-determined, free agents.

Only by a massive psychological campaign could the menace of overproduction in America be contained. That’s what important men and academics called it. The ability of Americans to think as independent producers had to be curtailed. Certain writings of Alexander Inglis carry a hint of schooling’s role in this ultimately successful project to curb the tendency of little people to compete with big companies. From 1880 to 1930, overproduction became a controlling metaphor among the managerial classes, and this idea would have a profound influence on the development of mass schooling.

I know how difficult it is for most of us who mow our lawns and walk our dogs to comprehend that long-range social engineering even exists, let alone that it began to dominate compulsion schooling nearly a century ago. Yet the 1934 edition of Ellwood P. Cubberley’s Public Education in the United States is explicit about what happened and why. As Cubberley puts it:

It has come to be desirable that children should not engage in productive labor. On the contrary, all recent thinking…[is] opposed to their doing so. Both the interests of organized labor and the interests of the nation have set against child labor.

The statement occurs in a section of Public Education called "A New Lengthening of the Period of Dependence," in which Cubberley explains that "the coming of the factory system" has made extended childhood necessary by depriving children of the training and education that farm and village life once gave. With the breakdown of home and village industries, the passing of chores, and the extinction of the apprenticeship system by large-scale production with its extreme division of labor (and the "all conquering march of machinery"), an army of workers has arisen, said Cubberley, who know nothing.

Furthermore, modern industry needs such workers. Sentimentality could not be allowed to stand in the way of progress. According to Cubberley, with "much ridicule from the public press" the old book-subject curriculum was set aside, replaced by a change in purpose and "a new psychology of instruction which came to us from abroad." That last mysterious reference to a new psychology is to practices of dumbed-down schooling common to England, Germany, and France, the three major world coal-powers (other than the United States), each of which had already converted its common population into an industrial proletariat.

Arthur Calhoun’s 1919 Social History of the Family notified the nation’s academics what was happening. Calhoun declared that the fondest wish of utopian writers was coming true, the child was passing from its family "into the custody of community experts." He offered a significant forecast, that in time we could expect to see public education "designed to check the mating of the unfit." Three years later, Mayor John F. Hylan of New York said in a public speech that the schools had been seized as an octopus would seize prey, by "an invisible government." He was referring specifically to certain actions of the Rockefeller Foundation and other corporate interests in New York City which preceded the school riots of 1917.

The 1920s were a boom period for forced schooling as well as for the stock market. In 1928, a well-regarded volume called A Sociological Philosophy of Education claimed, "It is the business of teachers to run not merely schools but the world." A year later, the famous creator of educational psychology, Edward Thorndike of Columbia Teachers College, announced, "Academic subjects are of little value." William Kirkpatrick, his colleague at Teachers College, boasted in Education and the Social Crisis that the whole tradition of rearing the young was being made over by experts.

The Geneticist’s Manifesto

Homeschooling at the S...

Best Price: $3.47

Buy New $9.01

(as of 11:05 UTC - Details)

Homeschooling at the S...

Best Price: $3.47

Buy New $9.01

(as of 11:05 UTC - Details)

Meanwhile, at the project offices of an important employer of experts, the Rockefeller Foundation, friends were hearing from Max Mason, its president, that a comprehensive national program was underway to allow, in Mason’s words, "the control of human behavior." This dazzling ambition was announced on April 11, 1933. Schooling figured prominently in the design.

Rockefeller had been inspired by the work of Eastern European scientist Hermann Müller to invest heavily in genetics. Müller had used x-rays to override genetic law, inducing mutations in fruit flies. This seemed to open the door to the scientific control of life itself. Müller preached that planned breeding would bring mankind to paradise faster than God. His proposal received enthusiastic endorsement from the greatest scientists of the day as well as from powerful economic interests.

Müller would win the Nobel Prize, reduce his proposal to a fifteen-hundred-word Geneticists’ Manifesto, and watch with satisfaction as twenty-two distinguished American and British biologists of the day signed it. The state must prepare to consciously guide human sexual selection, said Müller. School would have to separate worthwhile breeders from those slated for termination.

Just a few months before this report was released, an executive director of the National Education Association announced that his organization expected "to accomplish by education what dictators in Europe are seeking to do by compulsion and force." You can’t get much clearer than that. WWII drove the project underground, but hardly retarded its momentum. Following cessation of global hostilities, school became a major domestic battleground for the scientific rationalization of social affairs through compulsory indoctrination. Great private corporate foundations led the way.

Participatory Democracy Put To The Sword

Thirty-odd years later, between 1967 and 1974, teacher training in the United States was covertly revamped through coordinated efforts of a small number of private foundations, select universities, global corporations, think tanks, and government agencies, all coordinated through the U.S. Office of Education and through key state education departments like those in California, Texas, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and New York.

Important milestones of the transformation were: 1) an extensive government exercise in futurology called Designing Education for the Future, 2) the Behavioral Science Teacher Education Project, and 3) Benjamin Bloom’s multivolume Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, an enormous manual of over a thousand pages which, in time, impacted every school in America. While other documents exist, these three are appropriate touchstones of the whole, serving to make clear the nature of the project underway.

Take them one by one and savor each. Designing Education, produced by the Education Department, redefined the term "education" after the Prussian fashion as "a means to achieve important economic and social goals of a national character." State education agencies would henceforth act as on-site federal enforcers, ensuring the compliance of local schools with central directives. Each state education department was assigned the task of becoming "an agent of change" and advised to "lose its independent identity as well as its authority," in order to "form a partnership with the federal government."

The second document, the gigantic Behavioral Science Teacher Education Project, outlined teaching reforms to be forced on the country after 1967. If you ever want to hunt this thing down, it bears the U.S. Office of Education Contract Number OEC-0-9-320424-4042 (B10). The document sets out clearly the intentions of its creators — nothing less than "impersonal manipulation" through schooling of a future America in which "few will be able to maintain control over their opinions," an America in which "each individual receives at birth a multi-purpose identification number" which enables employers and other controllers to keep track of underlings and to expose them to direct or subliminal influence when necessary. Readers learned that "chemical experimentation" on minors would be normal procedure in this post-1967 world, a pointed foreshadowing of the massive Ritalin interventions which now accompany the practice of forced schooling.

The Behavioral Science Teacher Education Project identified the future as one "in which a small elite" will control all important matters, one where participatory democracy will largely disappear. Children are made to see, through school experiences, that their classmates are so cruel and irresponsible, so inadequate to the task of self-discipline, and so ignorant they need to be controlled and regulated for society’s good. Under such a logical regime, school terror can only be regarded as good advertising. It is sobering to think of mass schooling as a vast demonstration project of human inadequacy, but that is at least one of its functions.

Post-modern schooling, we are told, is to focus on "pleasure cultivation" and on "other attitudes and skills compatible with a non-work world." Thus the socialization classroom of the century’s beginning — itself a radical departure from schooling for mental and character development — can be seen to have evolved by 1967 into a full-scale laboratory for psychological experimentation.

School conversion was assisted powerfully by a curious phenomenon of the middle to late 1960s, a tremendous rise in school violence and general school chaos which followed a policy declaration (which seems to have occurred nationwide) that the disciplining of children must henceforth mimic the "due process" practice of the court system. Teachers and administrators were suddenly stripped of any effective ability to keep order in schools since the due process apparatus, of necessity a slow, deliberate matter, is completely inadequate to the continual outbreaks of childish mischief all schools experience.

Now, without the time-honored ad hoc armory of disciplinary tactics to fall back on, disorder spiraled out of control, passing from the realm of annoyance into more dangerous terrain entirely as word surged through student bodies that teacher hands were tied. And each outrageous event that reached the attention of the local press served as an advertisement for expert prescriptions. Who had ever seen kids behave this way? Time to surrender community involvement to the management of experts; time also for emergency measures like special education and Ritalin. During this entire period, lasting five to seven years, outside agencies like the Ford Foundation exercised the right to supervise whether "children’s rights" were being given due attention, fanning the flames hotter even long after trouble had become virtually unmanageable.

The Behavioral Science Teacher Education Project, published at the peak of this violence, informed teacher-training colleges that under such circumstances, teachers had to be trained as therapists; they must translate prescriptions of social psychology into "practical action" in the classroom. As curriculum had been redefined, so teaching followed suit.

Third in the series of new gospel texts was Bloom’s Taxonomy, in his own words, "a tool to classify the ways individuals are to act, think, or feel as the result of some unit of instruction." Using methods of behavioral psychology, children would learn proper thoughts, feelings, and actions, and have their improper attitudes brought from home "remediated."

Dumbing Us Down: The H...

Best Price: $1.48

Buy New $15.59

(as of 03:50 UTC - Details)

Dumbing Us Down: The H...

Best Price: $1.48

Buy New $15.59

(as of 03:50 UTC - Details)

In all stages of the school experiment, testing was essential to localize the child’s mental state on an official rating scale. Bloom’s epic spawned important descendant forms: Mastery Learning, Outcomes-Based Education, and School to Work government-business collaborations. Each classified individuals for the convenience of social managers and businesses, each offered data useful in controlling the mind and movements of the young, mapping the next adult generation. But for what purpose? Why was this being done?

Bad Character As A Management Tool

A large piece of the answer can be found by reading between the lines of an article that appeared in the June 1998 issue of Foreign Affairs. Written by Mortimer Zuckerman, owner of U.S. News and World Report (and other major publications), the essay praises the American economy, characterizing its lead over Europe and Asia as so structurally grounded no nation can possibly catch up for 100 years. American workers and the American managerial system are unique.

You are intrigued, I hope. So was I. Unless you believe in master race biology, our advantage can only have come from training of the American young, in school and out, training which produces attitudes and behavior useful to management. What might these crucial determinants of business success be?

First, says Zuckerman, the American worker is a pushover. That’s my translation, not his, but I think it’s a fair take on what he means when he says the American is indifferent to everything but a paycheck. He doesn’t try to tell the boss his job. By contrast, Europe suffers from a strong "steam age" craft tradition where workers demand a large voice in decision-making. Asia is even worse off, because even though the Asian worker is silenced, tradition and government interfere with what business can do.

Next, says Zuckerman, workers in America live in constant panic; they know companies here owe them nothing as fellow human beings. Fear is our secret supercharger, giving management flexibility no other country has. In 1996, after five years of record profitability, almost half of all Americans in big business feared being laid off. This fear keeps a brake on wages.

Next, in the United States, human beings don’t make decisions, abstract formulas do; management by mathematical rules makes the company manager-proof as well as worker-proof.

Finally, our endless consumption completes the charmed circle, consumption driven by non-stop addiction to novelty, a habit which provides American business with the only reliable domestic market in the world. Elsewhere, in hard times business dries up, but not here; here we shop till we drop, mortgaging the future in bad times as well as good.

Can’t you feel in your bones Zuckerman is right? I have little doubt the fantastic wealth of American big business is psychologically and procedurally grounded in our form of schooling. The training field for these grotesque human qualities is the classroom. Schools train individuals to respond as a mass. Boys and girls are drilled in being bored, frightened, envious, emotionally needy, generally incomplete. A successful mass production economy requires such a clientele. A small business, small farm economy like that of the Amish requires individual competence, thoughtfulness, compassion, and universal participation; our own requires a managed mass of leveled, spiritless, anxious, familyless, friendless, godless, and obedient people who believe the difference between Cheers and Seinfeld is a subject worth arguing about.

The extreme wealth of American big business is the direct result of school having trained us in certain attitudes like a craving for novelty. That’s what the bells are for. They don’t ring so much as to say, "Now for something different."

An Enclosure Movement For Children

The secret of American schooling is that it doesn’t teach the way children learn, and it isn’t supposed to; school was engineered to serve a concealed command economy and a deliberately re-stratified social order. It wasn’t made for the benefit of kids and families as those individuals and institutions would define their own needs. School is the first impression children get of organized society; like most first impressions, it is the lasting one. Life according to school is dull and stupid, only consumption promises relief: Coke, Big Macs, fashion jeans, that’s where real meaning is found, that is the classroom’s lesson, however indirectly delivered.

The decisive dynamics which make forced schooling poisonous to healthy human development aren’t hard to spot. Work in classrooms isn’t significant work; it fails to satisfy real needs pressing on the individual; it doesn’t answer real questions experience raises in the young mind; it doesn’t contribute to solving any problem encountered in actual life. The net effect of making all schoolwork external to individual longings, experiences, questions, and problems is to render the victim listless. This phenomenon has been well-understood at least since the time of the British enclosure movement which forced small farmers off their land into factory work. Growth and mastery come only to those who vigorously self-direct. Initiating, creating, doing, reflecting, freely associating, enjoying privacy — these are precisely what the structures of schooling are set up to prevent, on one pretext or another.

As I watched it happen, it took about three years to break most kids, three years confined to environments of emotional neediness with nothing real to do. In such environments, songs, smiles, bright colors, cooperative games, and other tension-breakers do the work better than angry words and punishment. Years ago it struck me as more than a little odd that the Prussian government was the patron of Heinrich Pestalozzi, inventor of multicultural fun-and-games psychological elementary schooling, and of Friedrich Froebel, inventor of kindergarten. It struck me as odd that J.P. Morgan’s partner, Peabody, was instrumental in bringing Prussian schooling to the prostrate South after the Civil War. But after a while I began to see that behind the philanthropy lurked a rational economic purpose.

Home Learning Year by ...

Best Price: $1.48

Buy New $6.49

(as of 01:35 UTC - Details)

Home Learning Year by ...

Best Price: $1.48

Buy New $6.49

(as of 01:35 UTC - Details)

The strongest meshes of the school net are invisible. Constant bidding for a stranger’s attention creates a chemistry producing the common characteristics of modern schoolchildren: whining, dishonesty, malice, treachery, cruelty. Unceasing competition for official favor in the dramatic fish bowl of a classroom delivers cowardly children, little people sunk in chronic boredom, little people with no apparent purpose for being alive. The full significance of the classroom as a dramatic environment, as primarily a dramatic environment, has never been properly acknowledged or examined.

The most destructive dynamic is identical to that which causes caged rats to develop eccentric or even violent mannerisms when they press a bar for sustenance on an aperiodic reinforcement schedule (one where food is delivered at random, but the rat doesn’t suspect). Much of the weird behavior school kids display is a function of the aperiodic reinforcement schedule. And the endless confinement and inactivity to slowly drive children out of their minds. Trapped children, like trapped rats, need close management. Any rat psychologist will tell you that.

The Dangan

In the first decades of the twentieth century, a small group of soon-to-be-famous academics, symbolically led by John Dewey and Edward Thorndike of Columbia Teachers College, Ellwood P. Cubberley of Stanford, G. Stanley Hall of Clark, and an ambitious handful of others, energized and financed by major corporate and financial allies like Morgan, Astor, Whitney, Carnegie, and Rockefeller, decided to bend government schooling to the service of business and the political state — as it had been done a century before in Prussia.

Cubberley delicately voiced what was happening this way: "The nature of the national need must determine the character of the education provided." National need, of course, depends upon point of view. The NEA in 1930 sharpened our understanding by specifying in a resolution of its Department of Superintendence that what school served was an "effective use of capital" through which our "unprecedented wealth-producing power has been gained." When you look beyond the rhetoric of Left and Right, pronouncements like this mark the degree to which the organs of schooling had been transplanted into the corporate body of the new economy.

It’s important to keep in mind that no harm was meant by any designers or managers of this great project. It was only the law of nature as they perceived it, working progressively as capitalism itself did for the ultimate good of all. The real force behind the school effort came from true believers of many persuasions, linked together mainly by their belief that family and church were retrograde institutions standing in the way of progress. Far beyond the myriad practical details and economic considerations there existed a kind of grail-quest, an idea capable of catching the imagination of dreamers and firing the blood of zealots.

The entire academic community here and abroad had been Darwinized and Galtonized by this time and to this contingent school seemed an instrument for managing evolutionary destiny. In Thorndike’s memorable words, conditions for controlled selective breeding had to be set up before the new American industrial proletariat "took things into their own hands."

America was a frustrating petri dish in which to cultivate a managerial revolution, however, because of its historic freedom traditions. But thanks to the patronage of important men and institutions, a group of academics were enabled to visit mainland China to launch a modernization project known as the "New Thought Tide." Dewey himself lived in China for two years where pedagogical theories were inculcated in the Young Turk elements, then tested on a bewildered population which had recently been stripped of its ancient form of governance. A similar process was embedded in the new Russian state during the 1920s.

While American public opinion was unaware of this undertaking, some big-city school superintendents were wise to the fact that they were part of a global experiment. Listen to H.B. Wilson, superintendent of the Topeka schools:

The introduction of the American school into the Orient has broken up 40 centuries of conservatism. It has given us a new China, a new Japan, and is working marked progress in Turkey and the Philippines. The schools…are in a position to determine the lines of progress. (Motivation of School Work, 1916)

Thoughts like this don’t spring full-blown from the heads of men like Dr. Wilson of Topeka. They have to be planted there.

The Western-inspired and Western-financed Chinese revolution, following hard on the heels of the last desperate attempt by China to prevent the British government traffic in narcotic drugs there, placed that ancient province in a favorable state of anarchy for laboratory tests of mind-alteration technology. Out of this period rose a Chinese universal tracking procedure called "The Dangan," a continuous lifelong personnel file exposing every student’s intimate life history from birth through school and onwards. The Dangan constituted the ultimate overthrow of privacy. Today, nobody works in China without a Dangan.

By the mid-1960s preliminary work on an American Dangan was underway as information reservoirs attached to the school institution began to store personal information. A new class of expert like Ralph Tyler of the Carnegie Endowments quietly began to urge collection of personal data from students and its unification in computer code to enhance cross-referencing. Surreptitious data gathering was justified by Tyler as "the moral right of institutions."

Occasional Letter Number One

Between 1896 and 1920, a small group of industrialists and financiers, together with their private charitable foundations, subsidized university chairs, university researchers, and school administrators, spent more money on forced schooling than the government itself did. Carnegie and Rockefeller, as late as 1915, were spending more themselves. In this laissez-faire fashion a system of modern schooling was constructed without public participation. The motives for this are undoubtedly mixed, but it will be useful for you to hear a few excerpts from the first mission statement of Rockefeller’s General Education Board as they occur in a document called Occasional Letter Number One (1906):

In our dreams…people yield themselves with perfect docility to our molding hands. The present educational conventions [intellectual and character education] fade from our minds, and unhampered by tradition we work our own good will upon a grateful and responsive folk. We shall not try to make these people or any of their children into philosophers or men of learning or men of science. We have not to raise up from among them authors, educators, poets or men of letters. We shall not search for embryo great artists, painters, musicians, nor lawyers, doctors, preachers, politicians, statesmen, of whom we have ample supply. The task we set before ourselves is very simple…we will organize children…and teach them to do in a perfect way the things their fathers and mothers are doing in an imperfect way.

This mission statement will reward multiple rereadings.

Change Agents Infiltrate

By 1971, the U.S. Office of Education was deeply committed to accessing private lives and thoughts of children. In that year it granted contracts for seven volumes of "change-agent" studies to the RAND Corporation. Change-agent training was launched with federal funding under the Education Professions Development Act. In time the fascinating volume Change Agents Guide to Innovation in Education appeared, following which grants were awarded to teacher training programs for the development of change agents. Six more RAND manuals were subsequently distributed, enlarging the scope of change agentry.

In 1973, Catherine Barrett, president of the National Education Association, said, "Dramatic changes in the way we raise our children are indicated, particularly in terms of schooling…we will be agents of change." By 1989, a senior director of the Mid-Continent Regional Educational Laboratory told the fifty governors of American states that year assembled to discuss government schooling. "What we’re into is total restructuring of society." It doesn’t get much plainer than that. There is no record of a single governor objecting.

Two years later Gerald Bracey, a leading professional promoter of government schooling, wrote in his annual report to clients: "We must continue to produce an uneducated social class." Overproduction was the bogey of industrialists in 1900; a century later underproduction made possible by dumbed-down schooling had still to keep that disease in check.

Government Schools Are...

Best Price: $3.96

Buy New $4.99

(as of 09:05 UTC - Details)

Government Schools Are...

Best Price: $3.96

Buy New $4.99

(as of 09:05 UTC - Details)

Bionomics

The crude power and resources to make twentieth-century forced schooling happen as it did came from large corporations and the federal government, from powerful, long-established families, and from the universities, now swollen with recruits from the declining Protestant ministry and from once-clerical families. All this is easy enough to trace once you know it’s there. But the soul of the thing was far more complex, an amalgam of ancient religious doctrine, utopian philosophy, and European/Asiatic strong-state politics mixed together and distilled. The great faade behind which this was happening was a new enlightenment: scientific scholarship in league with German research values brought to America in the last half of the nineteenth-century. Modern German tradition always assigned universities the primary task of directly serving industry and the political state, but that was a radical contradiction of American tradition to serve the individual and the family.

Indiana University provides a sharp insight into the kind of science-fictional consciousness developing outside the mostly irrelevant debate conducted in the press about schooling, a debate proceeding on early nineteenth century lines. By 1900, a special discipline existed at Indiana for elite students: Bionomics. Invitees were hand-picked by college president David Starr Jordan, who created and taught the course. It dealt with the why and how of producing a new evolutionary ruling class, although that characterization, suggesting as it does kings, dukes, and princes, is somewhat misleading. In the new scientific era dawning, the ruling class were those managers trained in the goals and procedures of new systems. Jordan did so well at Bionomics he was soon invited into the major leagues of university existence, (an invitation extended personally by rail tycoon Leland Stanford) to become first president of Stanford University, a school inspired by Andrew Carnegie’s famous "Gospel of Wealth" essay. Jordan remained president of Stanford for thirty years.

Bionomics acquired its direct link with forced schooling in a fortuitous fashion. When he left Indiana, Jordan eventually reached back to get his star Bionomics protégé, Ellwood P. Cubberley, to become dean of Teacher Education at Stanford. In this heady position, young Cubberley made himself a reigning aristocrat of the new institution. He wrote a history of American schooling which became the standard of the school business for the next fifty years; he assembled a national syndicate which controlled administrative posts from coast to coast. Cubberley was the man to see, the kingmaker in American school life until its pattern was set in stone.

Did the abstract and rather arcane discipline of Bionomics have any effect on real life? Well, consider this: the first formal legislation making forced sterilization a legal act on planet Earth was passed, not in Germany or Japan, but in the American state of Indiana, a law which became official in the famous 1927 Supreme Court test case Buck vs. Bell. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote the majority opinion allowing seventeen-year-old Carrie Buck to be sterilized against her will to prevent her "degenerate offspring," in Holmes’ words, from being born. Twenty years after the momentous decision, in the trial of German doctors at Nuremberg, Nazi physicians testified that their precedents were American — aimed at combating racial degeneracy. The German name for forced sterilization was "the Indiana Procedure."

To say this bionomical spirit infected public schooling is only to say birds fly. Once you know it’s there, the principle jumps out at you from behind every school bush. It suffused public discourse in many areas where it had claimed superior insight. Walter Lippmann, in 1922, demanded "severe restrictions on public debate," in light of the allegedly enormous number of feeble-minded Americans. The old ideal of participatory democracy was insane, according to Lippmann.

The theme of scientifically controlled breeding interacted in a complex way with the old Prussian ideal of a logical society run by experts loyal to the state. It also echoed the idea of British state religion and political society that God Himself had appointed the social classes. What gradually began to emerge from this was a Darwinian caste-based American version of institutional schooling remote-controlled at long distance, administered through a growing army of hired hands, layered into intricate pedagogical hierarchies on the old Roman principle of divide and conquer. Meanwhile, in the larger world, assisted mightily by intense concentration of ownership in the new electronic media, developments moved swiftly also.

The Well-Trained Mind:...

Best Price: $2.63

Buy New $12.00

(as of 02:30 UTC - Details)

The Well-Trained Mind:...

Best Price: $2.63

Buy New $12.00

(as of 02:30 UTC - Details)

In 1928, Edward L. Bernays, godfather of the new craft of spin control we call "public relations," told the readers of his book Crystallizing Public Opinion that "invisible power" was now in control of every aspect of American life. Democracy, said Bernays, was only a front for skillful wire-pulling. The necessary know-how to pull these crucial wires was available for sale to businessmen and policy people. Public imagination was controlled by shaping the minds of schoolchildren.

By 1944, a repudiation of Jefferson’s idea that mankind had natural rights was resonating in every corner of academic life. Any professor who expected free money from foundations, corporations, or government agencies had to play the scientific management string on his lute. In 1961, the concept of the political state as the sovereign principle surfaced dramatically in John F. Kennedy’s famous inaugural address in which his national audience was lectured, "Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country."

Thirty-five years later, Kennedy’s lofty Romanized rhetoric and metaphor were replaced by the tough-talking wise guy idiom of Time, instructing its readers in a 1996 cover story that "Democracy is in the worst interest of national goals." As Time reporters put it, "The modern world is too complex to allow the man or woman in the street to interfere in its management." Democracy was deemed a system for losers.

To a public desensitized to its rights and possibilities, frozen out of the national debate, to a public whose fate was in the hands of experts, the secret was in the open for those who could read entrails: the original American ideals had been repudiated by their guardians. School was best seen from this new perspective as the critical terminal on a production line to create a utopia resembling EPCOT Center, but with one important bionomical limitation: it wasn’t intended for everyone, at least not for very long, this utopia.

Out of Johns Hopkins in 1996 came this chilling news:

The American economy has grown massively since the mid 1960s, but workers’ real spendable wages are no higher than they were 30 years ago.

That from a book called Fat and Mean, about the significance of corporate downsizing. During the boom economy of the 1980s and 1990s, purchasing power rose for 20 percent of the population and actually declined 13 percent for the other four-fifths. Indeed, after inflation was factored in, purchasing power of a working couple in 1995 was only 8 percent greater than for a single working man in 1905; this steep decline in common prosperity over ninety years forced both parents from home and deposited kids in the management systems of daycare, extended schooling, and commercial entertainment. Despite the century-long harangue that schooling was the cure for unevenly spread wealth, exactly the reverse occurred — wealth was 250 percent more concentrated at century’s end than at its beginning.

I don’t mean to be inflammatory, but it’s as if government schooling made people dumber, not brighter; made families weaker, not stronger; ruined formal religion with its hard-sell exclusion of God; set the class structure in stone by dividing children into classes and setting them against one another; and has been midwife to an alarming concentration of wealth and power in the hands of a fraction of the national community.

Waking Up Angry

Throughout most of my long school career I woke up angry in the morning, went through the school day angry, went to sleep angry at night. Anger was the fuel that drove me to spend thirty years trying to master this destructive institution.

John Taylor Gatto is available for speaking engagements and consulting. Write him at P.O. Box 562, Oxford, NY 13830 or call him at 607-843-8418 or 212-874-3631.